Should Science be used to kill people?

After the recent vote to approve the renewal of the submarines carrying Britain’s Trident nuclear deterrent, we decided to pit two Science & Tech writers against each other to answer a simple question: Should Science be used to kill people?

Reece Goodall says YES:

As the government pushes a vote to renew the Trident defence system, debate rages on both sides. There are good reasons for and against it, but one poor one keeps raising its head – that we wouldn’t use them, and therefore they are pointless. But it glosses over the issue – the fact that we have the scientific and military capability to respond to threats, in a world that is increasingly dangerous and in which new enemies keep emerging, definitely makes our nation safer.

You can’t drop out of a scientific arms race because you have an idealised vision of winning peace by asking nicely for it – to not pursue military applications of science is fundamentally irresponsible, and it opens a country up to severe damage.

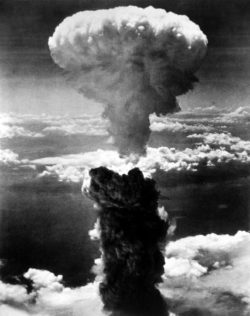

The clearest example of this is Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The USA, faced with a war that was going to drag on for years and years, and an enemy that refused to surrender, decided to exercise its technological might and drop two atomic bombs on Japan – the war ended. Countless lives were saved (the bombings killed about 150,000 people – by contrast, any other method would have resulted in more bloodshed and death, with Japan predicted it would lose 20 million people defending itself), and science stopped an enemy that would not be stopped otherwise.

Nothing good ever came of just sticking your head in the sand

I’m not particularly eager to be killing people, but our enemies are developing who-knows-what to hurt us. To not think of military uses of science is cowardly, weak and foolhardy – nothing good ever came of just sticking your head in the sand.

‘Anonymous’ says NO:

Using science and technology for a military enhancement, at this stage in time, is impractical. The West’s technology is currently superior to that of their enemies. The atom bombs of North Korea that have been reported to be fairly ineffective are a great example of this. In addition, ISIS currently don’t have a strong foothold on nuclear weapons.

HMS Victorious, a submarine that makes up part of Trident, the UK’s nuclear deterrent. Image: Defence Images / Flickr

According to Kurzgesagt, war is actually decreasing across the world, even with the continued rise of Islamic extremism. There are 9 countries in the world with nuclear weapon access. The U.K. has the third greatest nuclear capability, behind the US and Russia. Britain’s low number of foreign enemies, both currently and in the foreseeable future, means that the need for nuclear weapons is small.

Therefore, there is perhaps little need for using science and technology for military enhancement. There is a requirement for nuclear weapons, as a basic level of strategic defence, but no more than that. Instead, the money could otherwise be funnelled into academia or industry in order to create further technological advances, and to help build future generations of better scientific researchers.

There is a requirement for nuclear weapons, as a basic level of strategic defence, but no more than that

In addition, technology could be used to prevent war, rather than be used in it, for instance by disabling an enemy’s weapons before they can be used. Furthermore, this would then only be necessary if a major world war was occurring in the first place.

Comments (1)

Thou shalt not kill!! Maranatha na!