Hong Kong elections: four years later

Hong Kong, a southern Chinese city smaller than London, once dominated global media with images of mass protests, tear gas, and petrol bombs in 2019. Then, the pandemic hit, protestors were arrested, and civil society was silenced. Under the 24-hour news cycle, the coverage of Hong Kong in Western media was replaced by Covid-19 and the Ukrainian invasion. Despite the reduced presence in Western media, the political landscape of Hong Kong never stopped evolving. On 10 December 2023, the Hong Kong District Council elections were held for the first time since 2020. Marked by a record-low voter turnout of 27.5%, it was described as a “patriots only election” by Western media.

Therefore, the District Council elections are the most representative in a limited democracy

Local elections are deemed less important than general elections in the UK, but the District Council elections are historically and politically significant in Hong Kong. In the last decade of colonial rule, the British government sped up democratisation in Hong Kong before the handover to China in 1997. District Councils, established in 1982, are the first administrative bodies wholly and directly elected by the people. Hong Kong citizens can also vote for the Legislative Council, whereas the Executive Council is appointed by the Chief Executive which is in turn appointed by Beijing. Therefore, the District Council elections are the most representative in a limited democracy.

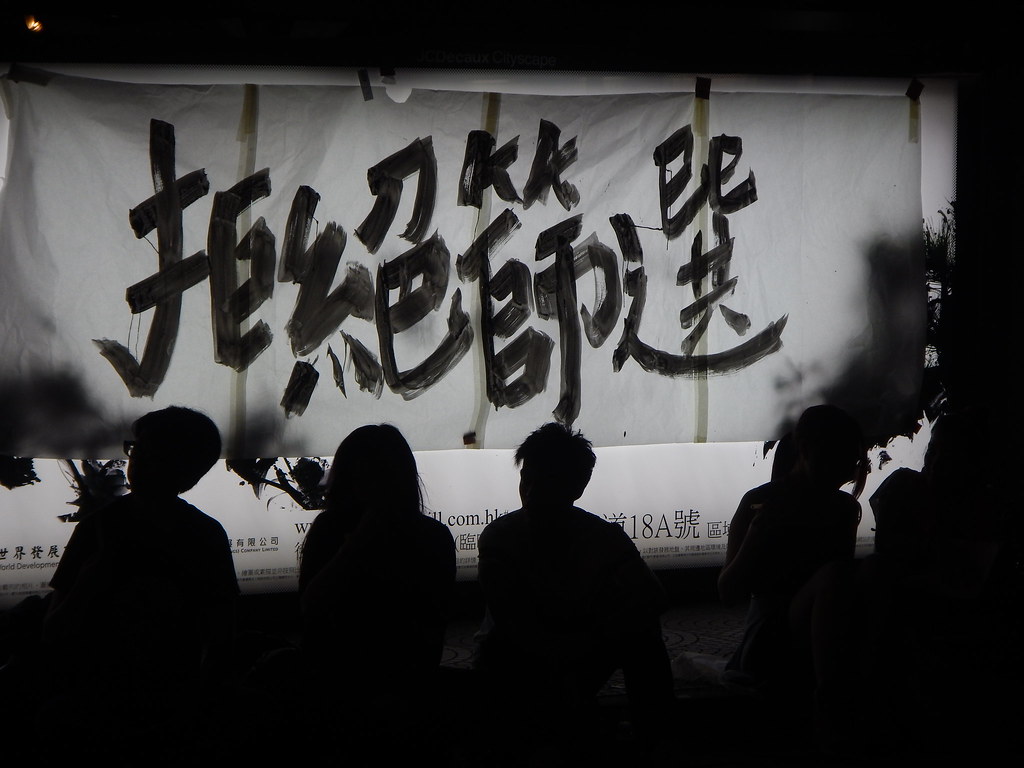

Hong Kong citizens were not always active in the District Council elections. Before 2019, its turnout was never higher than 47%, and the pro-Beijing camp controlled the largest share of election seats. The series of mass protests in 2019 swiftly reversed the power structure and raised public political consciousness. The protests were sparked by the 2019 Extradition Bill which empowered the government to transfer fugitives to Mainland China. The scale and violence of the movement increased due to police brutality and the general lack of democracy. In the largest demonstration in Hong Kong’s history, nearly two million people took to the streets.

At last, the pro-democracy camp won a landslide victory, securing almost 90% of the seats

The 2019 District Council elections took place at the peak of the movement. The desperately strong political awareness and discontent against the government pushed the turnout to an unprecedented 71%. Many young political neophytes nominated themselves, so no seat was left uncontested for the first time ever. At last, the pro-democracy camp won a landslide victory, securing almost 90% of the seats. Outside each ballot station, there were long queues during the day, volunteers monitoring the vote counting in the evening, and crowds cheering with champagne at midnight.

Four years is more than enough for an authority to kill democracy. As part of a broader crackdown on Hong Kong’s pro-democracy camp, the electoral system for District Councils was reformed. Now, candidates are all pro-Beijing, all of them having to have been nominated by pro-Beijing ‘patriotic committees’ to get on the ballot paper. The dismantling of the most representative electoral system in China began in June 2020, when Beijing passed the new national security law for Hong Kong. Then, ‘national security’ became the most common excuse the government used to crack down on civil activism. After a few months, Beijing adopted a decision disqualifying Hong Kong legislators who “endanger national security”. Four legislators were immediately expelled. The remaining pro-democracy counterparts resigned en masse to show solidarity, or simply out of fear of the new security law.

Resignation did not save them from being arrested. In January 2021, the mass arrest of 47 pro-democracy figures struck the city. They included legislators, district officials, activists, a former journalist, and a university professor. Under the growing political pressure, the wave of resignation spread to the District Councils where 230 elected pro-democrats left in 2021. At the same time, independent media outlets were shut under political pressure or by the government one after the other, and social gathering was still restricted by Covid-19 regulations.

The opposition had all but gone, but electoral reform was essential for Beijing to prevent its revival. In March 2021, Beijing passed the “patriots governing Hong Kong” resolution. It nearly halved the number of directly elected seats in the Legislative Council, and stipulated that all candidates in elections must pass a national security background check. Also, Legislative and District Council candidates must be nominated by the pro-Beijing Election Committee and pro-government local committees respectively.

After two years, electoral reform trickled down to the district level. In July 2023, the Legislative Council unanimously voted to reduce the proportion of directly elected seats on District Councils from 90% to 20%, even lower than the level in the 1980s. The rest of the 470 seats are appointed by the Chief Executive and local committees. The reform of the District Councils, the last major political bodies chosen by the public, marked the end of democratic elections in Hong Kong.

The Chief Executive said he felt “encouraged” that the reform would bring Hong Kong to a new chapter, but the public was not excited. It was the first time that the pro-democracy camp was completely absent in the district election. Unlike previous elections, streets were not stormed with the hype of the election. Fewer candidates promoted themselves by projecting their manifesto on megaphones, or visiting different flats. Some people even did not seek to know the candidates, not to mention volunteering in the campaigns like many did in 2019.

Insisting that the new voting system would “select the best”, the Hong Kong government tried hard to incite public interest in the election. Ahead of the election, there was a “fun day” with free museum visits, concerts, and a photography exhibition featuring the police force. Cathay Pacific offered discount flights for Hong Kong residents in Mainland China to return, while border zone ballot stations allowed eligible voters in China to vote. The government also sponsored elderly homes to take seniors to the polls, and those voting received a thank-you card and a photo opportunity.

Ironically, some pro-Beijing legislators did not like the new election system. Candidates from at least three pro-Beijing parties could not meet the threshold. Michael Tien, a pro-Beijing legislator, complained that they could hardly meet the committee members holding the nominating power. He suggested that meeting the threshold for running in the elections was “ten times harder” than for the Legislative Council election. Most candidates belonged to the largest traditional pro-Beijing parties, where the committee members came from. The new nominating system not only eliminated the pro-democracy candidates but also marginalised the small pro-Beijing parties.

The government tried to make the election celebratory, but there was a tense mood in the city on election day. Over 10,000 police officers were deployed, and at least six people were arrested for offences like posting online to encourage people to cast invalid ballots. They were a few of the over 10,000 people arrested for political reasons since 2019. Some voters showed their grievances in a less risky way, such as dropping campaigning leaflets into a urinal.

More of them simply boycotted the election. The turnout of 27.5% was the lowest since the end of colonial rule in 1997, yet was applauded as “good” by the Chief Executive. The election did not go smoothly despite the low public participation. The polling time was extended for 90 minutes after an electronic poll register system failure, and the Electoral Commission said the extension was not linked at all to the turnout rate.

The low turnout and technical issues overshadowed the actual election result, which was not reported by any Western media organisations. The Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), the largest pro-Beijing party, won the election with the highest number of candidates elected. 40% of the elected and appointed District Council members were those that lost elections in 2019.

People neither supported the new voting system, nor believed that the new line-up would bring them a better life, but they could not do anything. Thus, they just remained silent

The election results did not represent public opinion, on account of the voting system and the low turnout. However, they show the low public trust in the government. A strong sense of hopelessness has loomed over the city since 2019. News about the pandemic, the wave of emigration, small shops and book shops closing down, and the prosecution of political activists constantly conquer the few remaining non-patriotic media. Social problems, like the rising cost of living and the lack of work-life balance remain unresolved, adding insult to injury. In 2023, the happiness index even dropped to a 10-year low. People neither supported the new voting system, nor believed that the new line-up would bring them a better life, but they could not do anything. Thus, they just remained silent.

On the day of the election, the LGBT+ activist group ‘Pink Dot’ held its annual carnival. It is the largest LGBT+ festival in Hong Kong. Although the police force ordered the organisation to end the event earlier and strictly limited the number of attendants, everyone enjoyed the performance of local singers and drag queens a lot. The future of the city looks gloomy, but some people are trying their best to make it a bit brighter.

Comments