My parents’ Hong Kong classics

In my first seminar at Warwick, the tutor asked why we chose history. Many of my classmates said they began to love history because of the TV series Horrible Histories. Growing up in Hong Kong, I never watched Horrible Histories, so this was the first time I heard about this show. It was clear that, although we were studying the same course at the same university, we had different childhoods.

It appears that our parents have had different childhoods too. I googled ‘British cartoon 1970s’, and it seemed that the most terrific children’s TV programmes in the 70s were Mr Benn, Rainbow and Bagpuss. They all sounded unfamiliar to me because I had never heard my parents talk about them. To get a glimpse of my parents’ childhood, I gave them a phone call and asked what they watched when they were little. So, here’s the 70s for my parents—Hong Kong kids with a Hong Kong perspective.

From the 1970s to the early 2000s, this kind of anime was an important window for Asian children to European culture and classical literature

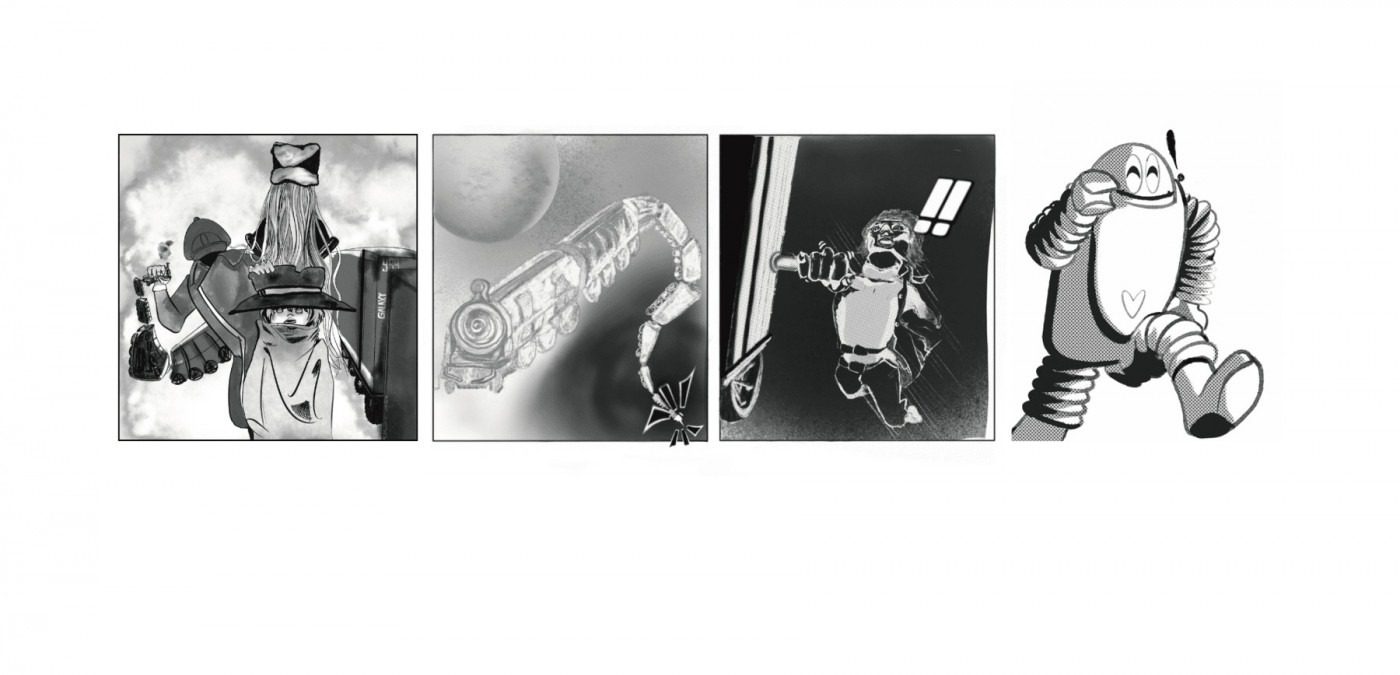

Just like most Hong Kong people in the 70s, my parents were immigrants from mainland China. When they fled to Hong Kong around GE six due to political instability in China, it was the golden era of Hong Kong’s economy and Japanese anime. Therefore, they grew up with Japanese animes which were spreading across Asia at that time. Most of the animes they watched were sci-fi, such as Galaxy Express 999 and Ganbare!! Robocon.

It is striking to see how avant-garde the 70s Japanese animes were. For example, Dr. Slump talks about how a scientist tries to build the perfect little girl robot, Arale, who turns out to be naive and loves playing with humans. Arale’s misunderstanding of humanity is humorous, but it touches upon our contemporary fear of AI and robotics. Furthermore, in the renowned cartoon Doraemon, the robot cat Doraemon always helps its human friends with many crazy gadgets. There is a smartwatch that allows users to watch videos and make recordings, ‘Mecha Maker’ that converts illustrations into real-life versions like 3D printing, and ‘Editorial Robot’ that generates comic books like ChatGPT. These futurist ideas not only brought joy to kids in the 1970s, but also impressed their children in the 2000s. Dr. Slump and Doraemon are undoubtedly two of my favourite cartoons. Broadcast at 4 p.m. every day, they motivated me to make sure I got all my homework finished at school before I went home.

However, some Japanese animes in the 1970s have a Western background. For instance, Heidi, Girl of the Alps is based on the Swiss children’s novel ‘Heidi’. Nobody’s Boy: Remi is adopted from the French novel ‘Sans Famille’ about a young boy working hard to earn money and see his foster family again. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, this kind of anime was an important window for Asian children to European culture and classical literature. I have never watched Nobody’s Boy: Remi, but I have watched the Japanese anime version of Les Misérables and Long Leg Daddy. I learned about the idea of revolution from them, and, funnily enough, I once thought characters in this kind of anime were the most beautiful because they all had blonde hair and blue eyes.

I found that TV programmes eliminated the 30-year age gap between my parents and me

But in addition to cartoons, my parents watched quite a lot of TV dramas. Unlike the Japanese animes that fulfilled children’s fantasies of future technology and superpowers, the TV dramas my parents watched are very realistic and locally produced in Hong Kong. Crocodile Tears portrays how a young journalist failed to pursue his dream in the capitalist world, whereas Fatherland is a historical drama about the plight of farmers in Southern China. Focusing on the political tragedy in mainland China and social inequality in colonial Hong Kong, these dramas were trendy at the time. They remain very influential; Gen Z might have even heard about them indirectly at some point. They were always re-played on TV when I was little, and I still see them on memes nowadays.

I found that TV programmes eliminated the 30-year age gap between my parents and me. They let me watch their childhood favourites when I was little, and, in turn, I’ve recommended my favourites to them. Our classical cartoons do not just live in the 70s; they are passed down through generations, both by family and love.

Comments