Post-impressionism: a naturalistic revolution in art

During this summer, I took a course that allowed me to travel through art history and its paintings. The first critical moment in modern art history this course brought me to was impressionism, and in particular, the effects of impressionism that took place from 1886 to the start of World War II in 1914, which I vividly saw at an exhibition in the National Gallery. This exhibition was fascinating as it focused on how Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cezanne, August Rodin, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Paul Gauguin utilised Claude Monet’s and Édouard Manet’s light brushstrokes to create a new pointillist approach to their paintings.

By the Deathbed used contrasting colours to convey the dark emotions he felt following his sister’s death from tuberculosis in 1877.

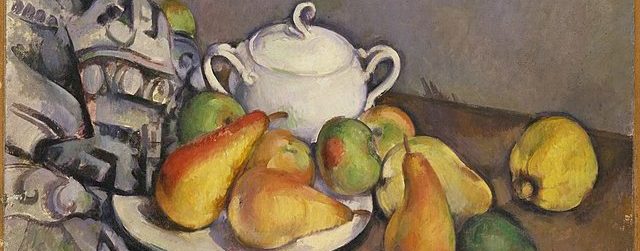

First, well-known impressionist painters were exhibited, each with a unique aesthetic perspective on a similar topic. One picture, however, stood out: Paul Cezanne’s ‘Sugar Bowl, Pears, and Tablecloth’. Its conventional subject matter and meticulous naturalistic execution, coupled with its distinctive pointillist colour technique, rendered it critical in this exhibition. This contrasts Van Gogh’s more emotional approach to his canvases.

When you leave the renowned artists, we enter the New Voices Barcelona & Brussels section. This is fascinating, as it examines how impressionist artists now have opportunities to exhibit art in Els Quatre Gats in Barcelona, and Les XX in Brussels. These new voices resulted in a fresh impressionist perspective that swayed more towards the development of the visual arts in Europe at the time. This caused a break in the conventional representation of the external world and the formation of non-naturalist visual languages, with an emphasis on the materiality of the art object expressed through line, colour, surface, texture, and pattern.

This led to European art communities expanding to other big cities, such as Vienna and Berlin. In Vienna, Wiener Werksatte became widely praised as he promoted a ‘total’ art that focused on dialogue. Whereas in Berlin, German Secessionists rose to popularity, which invited Norwegian and Scandinavian artists to also move to Germany to exhibit their art. One Norwegian artist, Edvard Munch, was particularly important in Berlin, as his expressionist painting ‘By the Deathbed’ used contrasting colours to convey the dark emotions he felt following his sister’s death from tuberculosis in 1877. On the other hand, Gustav Klimt marked his name in Vienna with the ‘Portrait of Hermine Gallia’. This painting represents the typical woman in the 19th century and is one key example of how impressionism is moving to a more expressive state in Europe, which focuses on conveying emotions through colour.

Paula Moderhsohn-Becker became the first woman recorded in history to depict herself naked and pregnant

This ‘new terrain,’ or the new expressionist direction it was moving towards, focused on “how art could be made, who had the right to make it, and what art could look like”. In Paris, a new style of paintings emerged, like ‘Seated Girl with a White Shirt and Standing Nude Girl’. This painting was critical not only for art’s development but also for feminism, as the artist Paula Moderhsohn-Becker became the first woman recorded in history to depict herself naked and pregnant. Meanwhile, in Berlin, the early 1900s saw the rise of artists such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, who was part of the artist group Die Brücke. This group consisted of artists who were recognised for their expressionism.

Rottluff’s painting ‘Break in the Dyke’ utilised intense colours, simplified forms, and bold outlines to highlight their influence on Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh’s work, but also to convey the move away from impressionism and towards a more non-naturalistic state in the 1910s.

Impressionism also spawned an array of new movements that were pivotal in twentieth-century art history, such as fauvism and cubism. Henri Matisse and Andre Derain characterised their work as ‘Fauves’ during the Salon d’Automne show in 1905. Fauvist artists attempted to stray from established aesthetic norms in order to elicit emotion and create a sense of movement and energy in their works. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque started breaking down things and forms into geometric shapes, usually resembling cubes, in the early 1900s. This allowed them to depict several sides of an object, resulting in a more complete representation that was not confined to a single point of view.

Despite portraying a lengthy era in art history, the exhibition helped me to expand my understanding of developments such as pointillism, impressionism, fauvism, cubism, and even expressionism. If you are interested in expanding your art knowledge and reside in London, I strongly propose that you see this show!

Comments