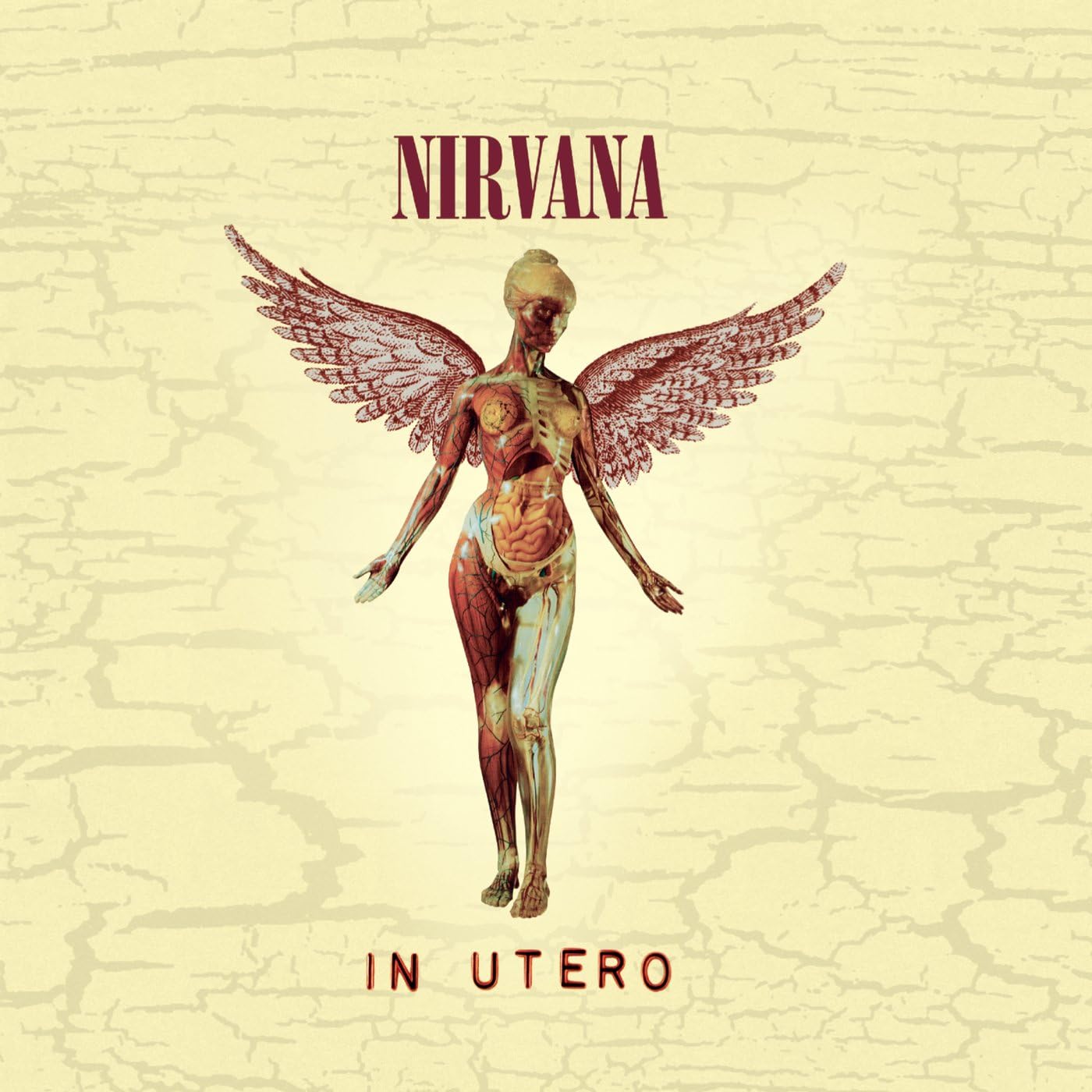

Nirvana’s seminal album, in Utero, turns 30: a retrospective

Adverbially, to be in utero is to be in a woman’s uterus. Adjectivally, it means happening before birth. This perhaps leaves In Utero, the raw and seminal third, and final studio album from Nirvana suspended in limbo. Far from the protective space between woman and baby, or rather band and album, In Utero has sold over 15 million copies worldwide since its release in 1993, leaving it vulnerable to the critique of the certified, and the less-than-certified, critics. Adverbially, then, it fails. Adjectively too: six months after the release of In Utero, Kurt Cobain was dead; far from happening before birth, In Utero happened before death.

It’s true, Cobain, as a man that was ‘tired of taking this band so seriously,’ might delight at such contradictions. In fact, the original name, I Hate Myself and I Want to Die, was intended as a joke against a world that saw him as a ‘pissy, complaining, freaked-out schizophrenic.’ In this sense, In Utero, is not an album suspended in limbo – nothing about the title, a phrase borrowed from a poem penned by Courtney Love, or the essence of the record ‘fails.’ Instead, it is Cobain at his most quintessential: fascinated with life, death, anatomy, and the punk-rock ethos of doing it your own way.

The legacy of In Utero can only be understood in relation to its predecessors.

But to look back at In Utero, whether after three or thirty years, one can’t help but see the eerie disconnect between the album’s name and the tragedy that transpired shortly after the album’s release. In Utero seems to foreshadow that tragedy. Yet, that story has been told, its sombre light cast again and again upon those events of the early Nineties – in short, it is far too easy to employ this form of historical revisionism. Thirty years ago, Cobain was alive, his artistry evolving, and Nirvana were the mainstream (whether they liked it or not). In Utero was the product of this, and now, thirty years later, it is an artefact of its time, hailed for its vision and authenticity.

But the legacy of In Utero can only be understood in relation to its predecessors.

If Bleach, Nirvana’s 1989 debut LP by independent champions Sub Pop, was just a drop in the ocean of music success, with its sludgy Seattle sound tapping almost exclusively into the underground punk scene to which Nirvana was adjacent, then 1991’s Nevermind was a tidal wave.

Chewing up and spitting out the status quo, leaving it unrecognisable, is a feat that very few albums have achieved. But Nevermind, with all of its contradictory prowess, as an album that is equal parts Beatles as it is Black Flag, made by a DIY band with the backing of major label DGC, did just that. Selling more than 30 million copies worldwide, Nirvana were no longer toeing the line between the underground and the mainstream – they had stormed straight across it. Nevermind had made them icons, and in doing so a grunge gold rush had begun as record labels turned over every stone in Seattle seeking their own musical goldmines. Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam – the underground had been unearthed.

But for righteous punk rockers, this was not a good thing. To them, Nirvana had ‘sold out.’ After all, Nevermind was a polished record, produced with the help of a major label, and promoted by the mainstream’s weapon of choice: MTV. Aware of this, Cobain sought to fortify his punk-rock credentials and from out of this storm, In Utero was born.

In recruiting the producer, Steve Albini (Pixies, The Breeders), the very DNA of In Utero was determined to be read as both punk and entirely distinct from the bubble-gum-sweet sounds of Nevermind. Working quickly, recording was completed in six days, with most tracks recorded live. Mixing took a further five days – quick by Nirvana’s standards, slow by Albini’s. The result? A raw record that was almost the antithesis of Nevermind – leaving DGC Records with a slightly sour taste in their mouths.

Although a compromise was forced between the band and DGC, with Scott Litt (R.E.M) being bought on board to remix the record in a more radio-friendly way, it is within the authentic producing and mixing process that the artistic charm of In Utero resides. ‘Of course,’ said Cobain, ‘they want another Nevermind, but I’d rather die than do that.’

Of frenzied intensity yet understated fragility, art and aggression, In Utero is a lesson in true disorder. Rockstar angst replaces teenage angst, and the mainstream is met with a sardonic grin as Cobain pushes against their mild inclinations. ‘Scentless Apprentice’ frames the abrasive direction the band had been moving towards, as visceral screams are aggravated by disturbing lyrics and darker basslines. Grohl is animalistic and, in parts, apoplectic, exhibiting his deftness behind the drum kit. ‘Rape Me,’ controversial for its fiercely feminist overtones, channels authentic rage, while ‘Pennyroyal Tea’ crescendos into choral fury in essential Nirvana fashion.

But buried inside this hysteria is soft reflection. There is almost a brittleness to the record, like glass, or old bones; with no way of relieving the intense pressure of some tracks, others show the cracks. ‘I’m not like them, but I can pretend,’ ‘Dumb’ is a bleak lullaby. ‘All Apologies’ is confession. By providing listeners with a place of refuge, with more soothing rhythms, the discomfort of the record can be keenly felt. Although docile in comparison, and considered to be ‘gateways’ to the more alternative sounds on the record by bassist Novoselic, these songs are no less dark.

In fact, no song is devoid of the themes of sickness and care, life and death. From the umbilical nooses of ‘Heart Shaped Box,’ to the parasitical pets of ‘Milk It,’ unease is the primary essence of In Utero. While this feeling is worsened retrospectively, with our knowledge of Cobain’s death just months later, not even Cobain’s claim that the record is impersonal, nor the fact that several songs were written as early as 1990, is able to dispel such discomfort. The songs, at best, are unsettling, at worst, plain ugly.

But in spite of this ugliness, or rather because of it, In Utero, thirty years on, is hauntingly beautiful. ‘This is exactly the kind of record I would buy as a fan, that I would enjoy owning,’ said Cobain. Millions agree: In Utero debuted at number one in the UK and the US. In 2011, a poll run by The Guardian saw In Utero ranked as Nirvana’s greatest album. Through its corrosive authenticity, In Utero exists as pure art. Through its unsettling essence, In Utero captivates.

Bleach is a diamond in the rough, Nevermind the crown jewel. As for In Utero? Well, take the crown jewel and smash it into smithereens. While for some the remaining crystallites will be invisible and invaluable, for those that know where to look, they will be cherished for their beauty amidst the destruction.

Comments (1)

Well, this is a very well written article, I’ve enjoyed reading. I find it most informative. Upon my own personal reflection.

(2023 year).