Russia to leave the International Space Station after 2024

Russia has announced that it will withdraw from the International Space Station (ISS) after 2024, and instead work on building its own station. The move was hardly unexpected, as relations with Russia have collapsed since the country invaded Ukraine – it previously threatened to quit the project in response to Western sanctions, and even suggested that it would crash the station into a Western nation deliberately. But, given the importance of Russia to the ISS throughout its history, the news is hardly encouraging from a scientific standpoint.

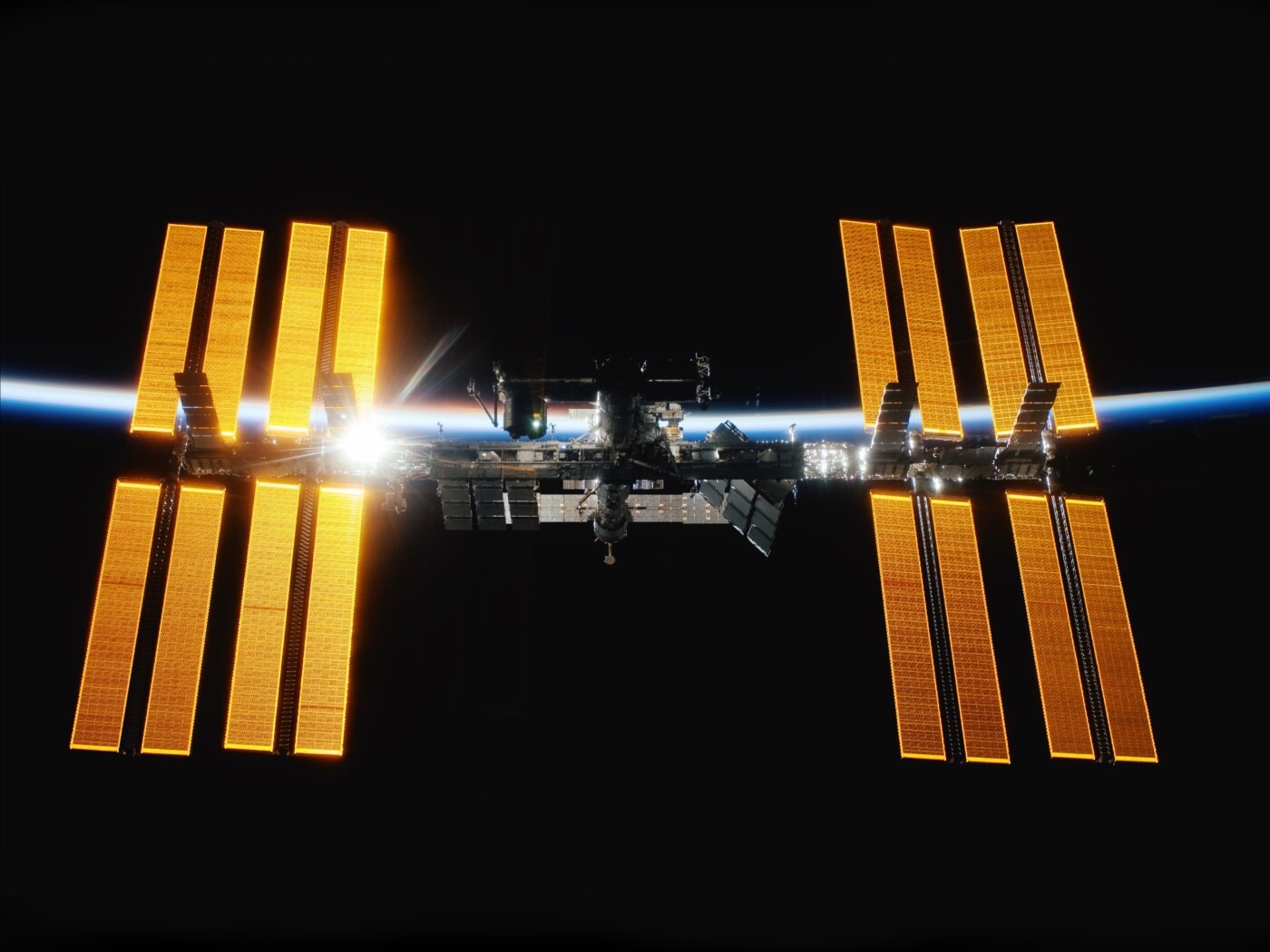

The first version of the ISS was launched in 1998, a joint project involving five space agencies, and it has been used to conduct many scientific experiments. Astronauts from a selection of Western countries and Russia have continuously lived there since 2000, the longest constant human presence in low Earth orbit in history. For a long time, the station was seen as a symbol of a lost-cold war partnership between the two space superpowers, and President Vladimir Putin lauded it as an example of the “very successful” bilateral ties between the two countries in 2001.

A senior NASA official said that Russia had not communicated its intent to withdraw from the ISS officially

That moment, it seems, has now passed. Even during the Ukrainian conflict, space seemed to be one remaining area of cooperation. In a meeting with Putin, Yuri Borisov, the newly appointed head of the space agency Roscosmos, said Russia would fulfil its obligations until 2024, and then leave the ISS. Mr Borisov said that “the decision to leave the station after 2024 has been made”, to which Putin simply replied: “Good.” Roscosmos then released an image of what it said was a blueprint for its own station, which would reportedly accommodate two Russian astronauts at first. This would eventually expand to four once the station is fully operational.

There are questions about how realistic this announcement is – a senior NASA official said that Russia had not communicated its intent to withdraw from the ISS officially. Former ISS commander and retired US astronaut Dr Leroy Chiao suggested it was unlikely the threats would come to pass: “I think this is posturing by the Russians. They don’t have the money to build their own station and it would take several years to do it. They’ve got nothing else if they go this route.” The financial commitment, especially for the sanction-hit Russian economy, would be a particularly hard one to make, and access to parts and technical equipment is increasingly limited.

The ISS would likely have to shift operations, as propulsion manoeuvres are directed by Moscow’s mission control

But if Russia did leave, what would it mean? The station is designed in such a way that the two superpowers are dependent on each other – the US side provides the power, and the Russian side provides the propulsion and prevents the ISS falling to Earth. If Russia withdrew, the US and its other partners (Europe, Japan, and Canada) will need to devise some other means of periodically boosting the station. The ISS would likely have to shift operations, as propulsion manoeuvres are directed by Moscow’s mission control, but the process is a complicated one because of the major logistical issues and safety challenges involved in controlling the spacecraft.

Coupled with this, there would be the question of who gets to use the ISS in the event of a Russian withdrawal. It’s impossible to essentially remove the Russian bits, and it’s yet to be figured out how other countries might take over the Russian segment of the station. John Logsdon, space historian and policy analyst at George Washington University, said that Russia should still be part of the discussions: “Reacting to this should be a collaborative thing.” He noted that, while Russia is one of the two main partners, it is “still a partner” and so should be included in the conversation. If these conversations come to nought, one possible solution is rendering the station obsolete before its proposed 2030 expiration.

Scott Pace, director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, suggests that the announcement was “mildly helpful” because it included a 2024 commitment. But past that date, there’s a lot of ambiguity about what will happen, and whether it’s worth even trying to save the station if Russia actually does withdraw. Astronomer Jonathan McDowell questions “how hard (NASA) really want to work to get an extra few years out of ISS”, and suggests that the better option may be using it as an excuse to develop future projects. The Russian announcement is forcing space agencies around the world to look to the future – the question is whether Moscow will still be part of it.

Comments