Turning the world upside down: the genius of CS Lewis’ Screwtape Letters

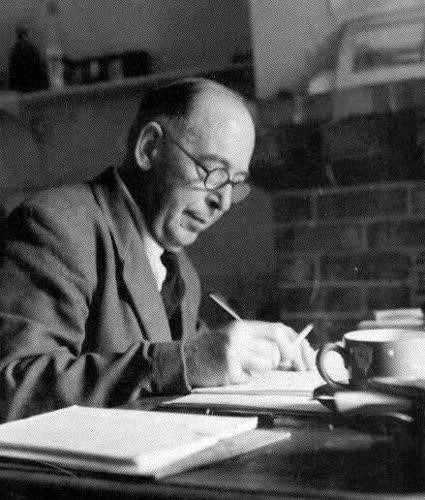

CS Lewis: writer, theologian, scholar – he’s predominantly known for such works such as The Chronicles of Narnia and his close relationships with celebrated writers like J.R.R. Tolkien. For Christians, C.S. Lewis would be a writer whose significance resides in their Christian apologetics. Like Tolkien, Lewis was profoundly Christian, which influenced his writing, resulting in efforts like Mere Christianity, The Problem of Pain, and, of course, The Screwtape Letters.

The Screwtape Letters was published in 1942 in dedication to Tolkien. It’s a satirical, epistolary novel that documents the correspondence between two demons (Screwtape and his apprentice Wormwood) centred around their objective to condemn their subject (a British man only known as “the patient”) to eternal damnation. Through this lens, Lewis engages with various theological and real-world problems and elucidates the daily ailments of human interaction with a Christian sheen.

As someone who’s beginning to take their Christian faith more seriously, reading this book was a must and it didn’t disappoint one bit. Despite its religiosity, Lewis acutely presents the interplay between demonology and the secular world: don’t be fooled, this book can fascinate anyone who’s observant and introspective about the human condition.

With each letter you’re able to understand that he’s a demon who’s quick-witted, sinisterly smart, competent, and ultimately God-hating.

The novel is constructed in a clever manner. The epistolary structure, with the plot unfolding through correspondence concerning a single man’s life, enables universal, human phenomena to be explored in a personal and relatable fashion. Through Screwtape’s comments and observations he relays to his apprentice Wormwood about the daily motivations, behaviours, and thoughts of their patient, we’re able to examine our own lives in relation to the themes and topics that are mentioned. Also, as the letters progress, we better understand the worlds the demons and the patient are in, with peppered references to the hierarchy (or “lowerarchy”) of the demon realm or Britain amidst the war. Of course, stylistically, it’s an engaging read: the epistolary style lends itself to candid expression and the emphasis on characterisation.

Characters like Screwtape are beautifully realised: with each letter you’re able to understand that he’s a demon who’s quick-witted, sinisterly smart, competent, and ultimately God-hating. Little phrases like “my dear Wormwood” that begin each entry, or referring to God as “the Enemy”, as well as his magnetic lexicon portray so much about his status, desires, role, and relationship with the hellish project. Plus, it’s as if Lewis uses the language and syntax to embody the character of Screwtape, whilst the content is devoted to the characters like the patient and wormwood: we can infer Wormwood’s naivety and self-doubt, or the patient’s hubris through the presentation provided by Screwtape.

It reminded me that I should be grateful to have been gifted time, even when it feels too painful to bear.

Though the lessons and ideas are by far the novel’s biggest triumph, Lewis depicts the common failings of human behaviour and interaction so skilfully that it’s equally profound and amusing. For instance, Letter 1 engages with how often people confuse their thoughts for actions, which is very pertinent given the age of social media and virtue signalling. It made me consider the Aristotelian virtues and ethics, and how truly actions and habits determine one’s character more than words and sentiments. Many people consider themselves good because they believe and think the ‘right’ things, rather than consistently doing right and just actions.

Letters 18 and 21 are very thought-provoking in their commentaries. In 18, Screwtape notes how modern culture demeans marriage on a contractual basis (e.g: for family building, salvation, or establishing generational wealth) because it’s too cynical, yet marriage under a “storm of emotion” like love or infatuation is deemed the ideal. It makes you wonder why divorce rates are so high, and whether our conceptions of love, marriage, and family need fundamental re-examination. Letter 21 exposes how our tendency to claim time is our own is nonsensical, given how we didn’t choose to be born, we can’t control many things outside of ourselves, and that our time can be taken at any moment. It reminded me that I should be grateful to have been gifted time, even when it feels too painful to bear.

I found letter 27 particularly illuminating because it deals with the intellectualising of ancient texts. This is relevant given I’m a history student who encounters older texts frequently. Screwtape mentions how intellectuals tend to be so fixated on the context of said text and its meaning, rather than seeking to decipher the truth in it. This made me reflect on the seminar discussions I’ve had during my time at university, and discussions do tend to be hinged more on a text’s place in history. I think the reluctance to engage the heart of texts means we run the risk of passing up on ancient wisdom or missing out on the truth of human existence that historical trends and literature may reveal.

Screwtape Letters was immensely successful and it’s clear why. The novel’s clever, systematic assessment of the human condition humbles you and reminds you of the ugliness that makes us who we are but knowing we always have the choice to become better. All the while, its structure whisks you into the realm of good vs evil, even if you’re not a believer the characters and the worlds they operate in are wonderfully sketched. I highly recommend this book to anyone who wishes to view their existence in a different light.

Comments