Is there a Planet Nine?

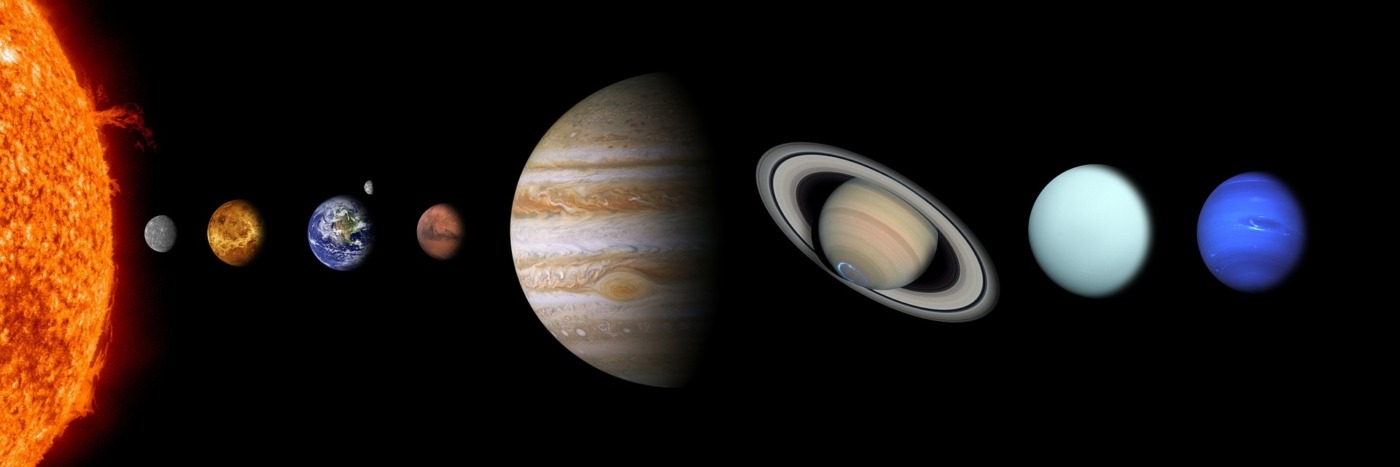

In 2006, Pluto was downgraded from a planet to the status of dwarf planet, meaning the Solar System is now only host to eight planets. But is that actually the case, or could there be another planet out there that astronomers are yet to discover? The idea may sound absurd, and it’s certainly not without controversy, but the Planet Nine hypothesis is an interesting one which may boast some evidence in its favour. What science underpins this mystery?

The obvious question is, if we haven’t found Planet Nine, why do we believe it’s actually there at all? In 1906, the Solar System was known to have eight planets. Uranus’ orbit seemed to show unexpected irregularities, and Percival Lowell began the search for what he named ‘Planet X’, a body that would cause these gravitational effect. Pluto was discovered in 1930 but, in 1978, it was determined to be too low in mass to be responsible. At the time, a possible tenth planet was then proposed, but the 1990s’ discovery that Neptune is less massive than astronomers first thought seemed to explain the discrepancies.

In 2016, the Planet Nine hypothesis – the idea that an additional giant planet beyond Neptune, on an inclined eccentric orbit – was proposed

In the early 21st century, however, a population of distant, eccentric Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) was discovered. They weren’t gravitationally influenced by Neptune, suggesting the presence of something else, which was causing the KBOs to cluster. In 2016, the Planet Nine hypothesis – the idea that an additional giant planet beyond Neptune, on an inclined eccentric orbit – was proposed as an explanation by Mike Brown and Konstantin of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). This planet would have a mass between five or six times that of Earth, and either a rocky super-Earth or a gaseous mini-Neptune. There was uncertainty about whether the orbital clustering was actually significant, or just the result of observational bias, but scientists have since effectively ruled that out.

Since 2016, approximately 19 objects were identified as following an unusual pattern of orbit. Any that may have been influenced by Neptune were then discounted, leaving 11 that may be affected by the gravitational pull of the theoretical planet. But if we know about its gravitational pull, and the fact that Professor Batygin has calculated a possible orbit, then why can’t we look to the sky and pick out Planet Nine? It’s not that simple – picking out one object in the universe is difficult, and it’s likely that the planet is at the far edge of its enormous orbit (one that may take between 10,000-20,000 years for a full cycle), meaning it’s unlikely to be reflecting much light from the Sun.

Of course, there may be another, more simple reason why we don’t see Planet Nine – because it may not even exist. But, if it doesn’t, then what could explain the gravitational disturbances? Some scientists believe it may be a primordial black hole (PBH), a hypothetical black hole that formed during the very first second of the universe’s existence. If that is the case, the PBH would likely by the diameter of a grapefruit, yet around 10 times heavier than the Earth. Other astronomers have suggested that the idea of Planet Nine may simply natural bias in sky surveys, and that there’s no way of knowing if the KBOs are actually acting strangely until we know more about them.

Last year, Prof Brown said: “I think it’s within a year or two from being found. I’ve made that statement every year for the past five years. I am super-optimistic.” He also suggested that it was likely images of the planet already exist in surveys, and simply hasn’t been identified as such – thus, there won’t be any need to wait for next-generation telescopes to come online to locate the planet. Other experts believe that, contrary to the Caltech experts, it’s too early to proclaim anything based on the limited existing data. It’s possible that, as the search continues, scientists will conclusively determine which side of the argument is right – either way, it’s likely that these attempts will produce a lot of interesting experimental data that will enrich our knowledge of the far reaches of our Solar System.

Comments