The BBC Gill statue – how should we protest art?

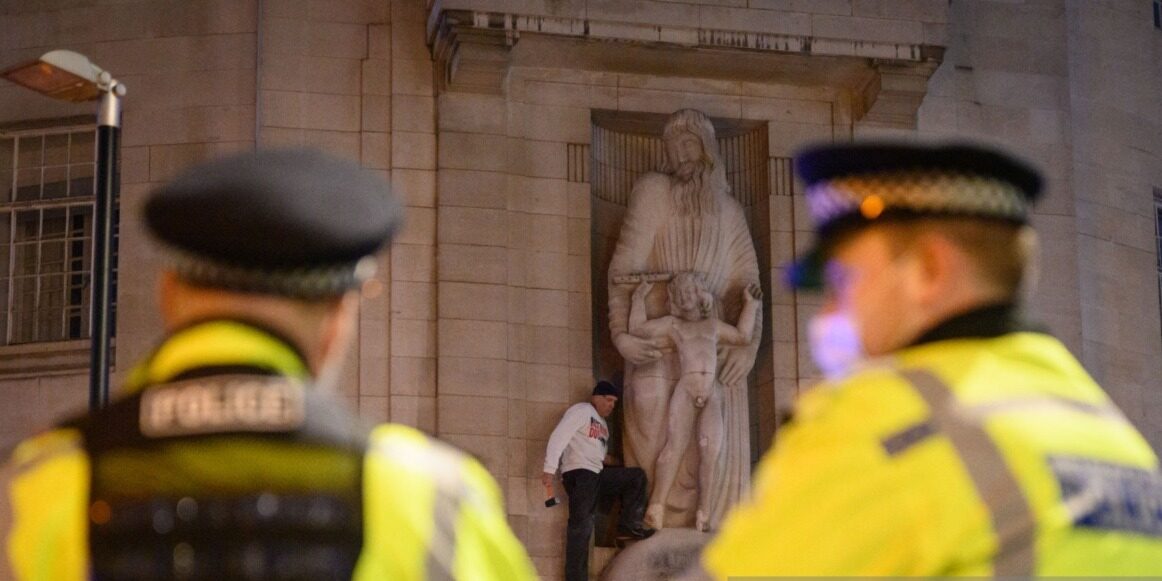

On 12 January, a man went to the BBC for a spot of statue smashing. The Metropolitan Police were called to Broadcasting House after a man climbed onto its front, using a hammer to attack a statue of Prospero and Ariel from The Tempest. The problem is that the artist behind the work was Eric Gill, a prominent British artist until his death in 1940, who was later revealed to be a sexual abuser through the posthumous publishing of his diaries. The man and his companion, who stood in the street shouting about paedophilia, objected to its presence, and tried to do something about it. The statue remains standing despite some minor damage, but it has again fuelled a familiar conversation – how should we protest controversial art?

Events like this don’t take place in a vacuum, in fact, there was a major story a week prior that must have paved the way

The statue was installed at the BBC in 1933, and this isn’t the first time it attracted criticism. There were concerns about the size of the sprite’s genitalia when it was first erected, and then the corporation faced calls from sexual abuse charities to remove the statue from its headquarters in 2013 but refused, citing Gill’s record as “one of the last century’s major British artists whose work has been widely displayed in leading UK museums and galleries”. However, a look at his personal history is hardly a savoury one. A biography on the Tate Museum website about Eric Gill said: “His religious views and subject matter contrast with his sexual behaviour, including his erotic art, and (as mentioned in his own diaries) his extramarital affairs and sexual abuse of his daughters, sisters and dog.” Unusually, most attacks on statues are due to the person they depict, rather than the artist themselves.

Events like this don’t take place in a vacuum, in fact, there was a major story a week prior that must have paved the way. On 5 January, the Colston Four were cleared of any criminal charges of damage. They were four of the protestors who, in June 2021, pulled down the statue of slave trader Edward Colston and threw it into Bristol’s harbourside. The group were accused of criminal damage, and none of them denied that they had pulled down the statue, but they successfully argued that they had acted in a just way. One of the defendants, Sage Willoughby, denied the group were trying to edit history and hit out at those he said “whitewashed history” by calling Colston “a virtuous man”: “We didn’t change history, we rectified it.”

what should happen to art when it is deemed problematic?

The acquittal reignited many of the debates that emerged when the statue was first pulled down. The historian David Olusoga, who testified at the trial, said: “The real offenders were not the Colston Four, but the city of Bristol and those who have done everything in their power to burnish the reputation of a mass murderer.” Although it was ostensibly a trial on the Colston Four, their acquittal suggests that Bristol and its governance are symbolically guilty. On the other side of the aisle, the group Save our Statues tweeted that it was a “disgraceful verdict that gives the green light to political vandalism and sets a precedent for anyone to be able to destroy whatever they disagree with”. There are now talks about referring the case to the Court of Appeal to clarify the law for future cases.

Very few historical artists were good people, and very few historical figures led lives that would not be considered contentious by modern standards – destroying art doesn’t change that

The questions raised by these cases are not new ones. Can we separate art from its artist? Does displaying art amount to an endorsement of the art or the figures it portrays? And what should happen to art when it is deemed problematic? There are no easy answers to these questions, and that’s what makes these debates so tricky – indeed, the two sides are often characterised by the two most extreme positions on either side, which helps no-one. My fear is that the Colston Four verdict will galvanise more people to actively try and destroy more art that they disagree with, and that’s a slippery slope. Very few historical artists were good people, and very few historical figures led lives that would not be considered contentious by modern standards – destroying art doesn’t change that. Grown-up conversations about how we discuss and recognise these people might, however, truly help put their work into its real context, both good and bad.

Comments