Last Night I Watched: ‘Unforgiven’

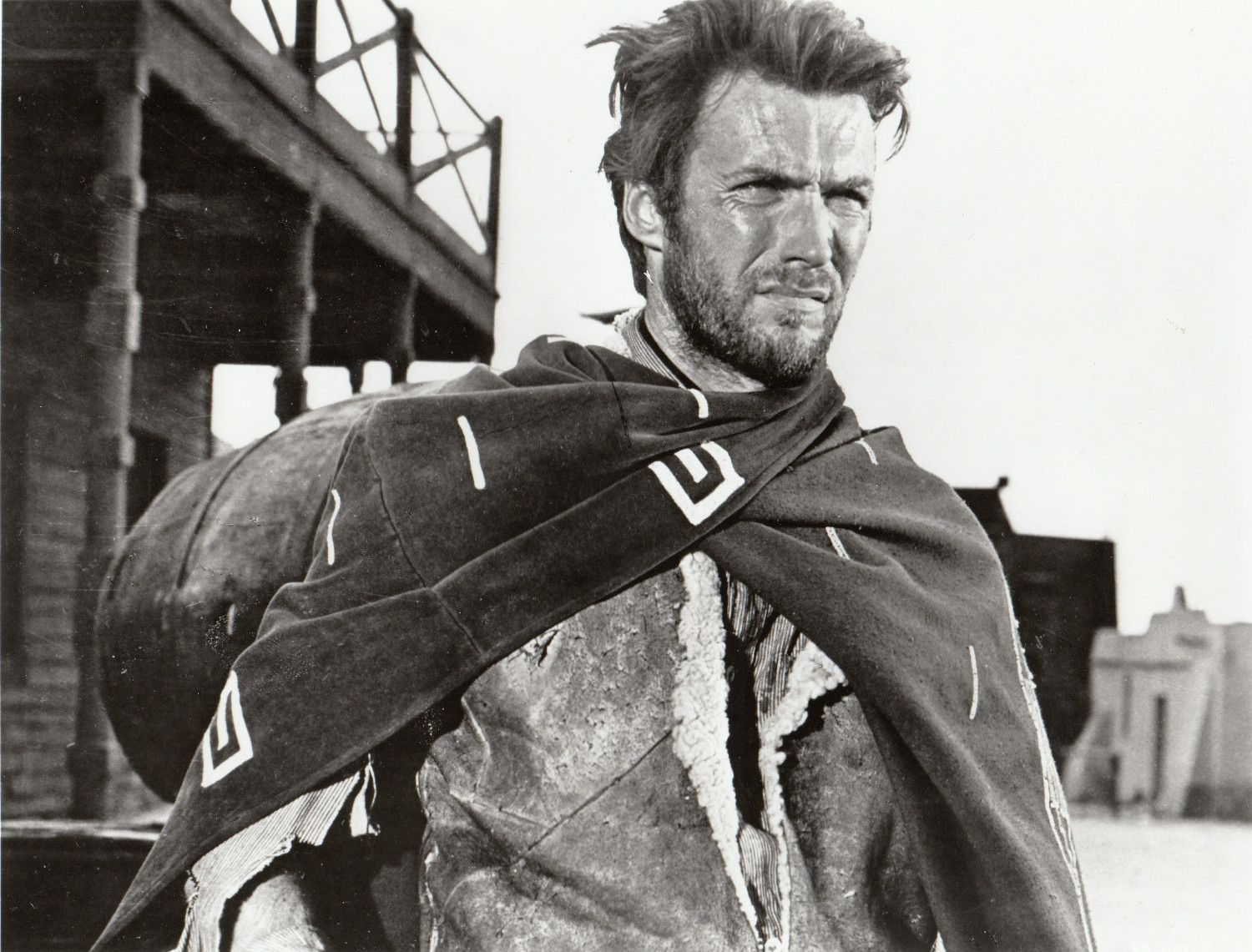

Here’s something you won’t hear too often nowadays – I like Westerns. The genre had its heyday long ago, and Hollywood has recognised this – when was the last time you saw a new Western film really capture an audience? There’s something about them, and I’d sit through all the classics as a kid, marvelling in tales of cowboys, gunfights and adventures. Well, all of them but one. I finally sat down to watch the last Western classic, Clint Eastwood’s 1992 film Unforgiven, and I was blown away. This is a Western, but not as we’ve ever seen before – it’s a stunning film that punctures so many of the myths we associate with the West, and is a fitting bookend to an essential Hollywood genre.

We begin in the town of Big Whisky, where a cowboy is carving up a prostitute’s face as his friend holds her, simply because she laughed at the size of his penis. The sheriff, Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman), a man who is both lawman and judge and operates as both with an iron fist, demands the cowboys give six horses to the brothel owner as compensation. But the prostitutes are not at all happy with this, and they put a $1,000 bounty on the cowboys’ heads in return.

This is not a romanticised view of the West, far from it

One of the people interested in claiming this money is the self-titled ‘Schofield Kid’ (Jaimz Woolvett), and he seeks out help. This brings him to William Munny (Clint Eastwood), a former outlaw and murderer who is now living as a repentant widower and father. He is not interested in reprising his old life, but he recognises that his farm is failing and his children need the money. Reluctantly, he sets off on the job, recruiting his old friend Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) to help him out.

This is not a romanticised view of the West, far from it. In a classic Western, we’re used to seeing our heroes gun down scores of bad guys, but that’s not the case in Unforgiven. Every life taken is painful and unclean, with the dying screams of the wounded haunting the soundscape. In one scene, a cowboy is dying slowly, a bullet in his gut, something that horrifies his friends and the men that shot him. The Schofield Kid is like us, a glory hunter revelling in stories of past exploits and eager to kill – when he finally executes a man, he breaks down in tears, devastating at what he has done. Prior to the murder, he felt that it was undoubtedly the right thing to do – the act committed, he realises that it was anything but.

Unforgiven is also a tale about stories, and it shatters our imagination of a glorious Western past. Nowhere is this truer than in the character of English Bob (Richard Harris), a gun-toting figure flanked by a novelist, W. W. Beauchamp (Saul Rubinek), who is writing the story of his life. Or, at least, he’s buying into Bob’s publicity and bravado, and finds it shattered in Big Whisky. Little Bill delights in disarming the Englishman and then mentally and physically beating him to set an example. The sheriff is brutal in demystifying classic stories, and happy to do so for Beauchamp. In a beautifully-acted scene, Little Bill breaks down the myth of the quick draw, and then gives a gun to Beauchamp to prove that it’s not easy to kill a man.

I’ve talked a lot about themes but, even outside of that, this is a wonderfully-crafted movie

Unlike in many classic Westerns, there is no grand battle between good and evil here – indeed, the labels blur into one and often don’t have much relevance anyway. It’s pointed to an extent that the good and bad roles of the sheriff and the outlaw are reversed, but it doesn’t mean too much. Little Bill is a monstrous figure, destroying English Bob and later torturing Logan to death, but it’s made clear that Munny is not a good person either – although he has given up his life of violence, he has never seriously made amends. In the film’s final confrontation, Munny embraces the dark side of his past, and puts an end to Little Bill’s sadistic ways. But this comes with boasts about his murder of women and children, and threats to kill the entire town if he is forced to return. We believe this, and it forces us to ask – if this is Unforgiven’s heroic climax, what exactly does heroism mean?

I’ve talked a lot about themes but, even outside of that, this is a wonderfully-crafted movie. David Webb Peoples’ screenplay is captivating, a detailed work of great moral complexity without ever being less than seamless. The cast are phenomenal, in a film that really requires some serious acting chops, and it looks stunning. The flats of the Alberta plains are beautiful, a magical setting amplified by Lennie Niehaus’ mournful score (boasting ‘Claudia’s Theme’, composed by Eastwood himself). As a swansong for the genre, it’s a perfect one, capturing everything that made the Western iconic even as it deconstructs it. Just look at the final fade-out, a subverted ride off into the night that is beautifully poetic. This is Eastwood’s best picture as director, undoubtedly, and he has a perfect eye for the story he’s telling.

It took me forever to watch Unforgiven, but I’m glad I finally have, because it truly is a masterpiece. It’s one of the great Westerns but, wider than that, it’s one of the great American films. If you’re a fan of the Western, you owe it to yourself to watch this film – if not, you can enjoy it as a painfully real tale of right and wrong, and a meditation on the value of the very stories that make up our history.

Comments