‘My Own Private Idaho’ was a benchmark for LGBT+ cinema

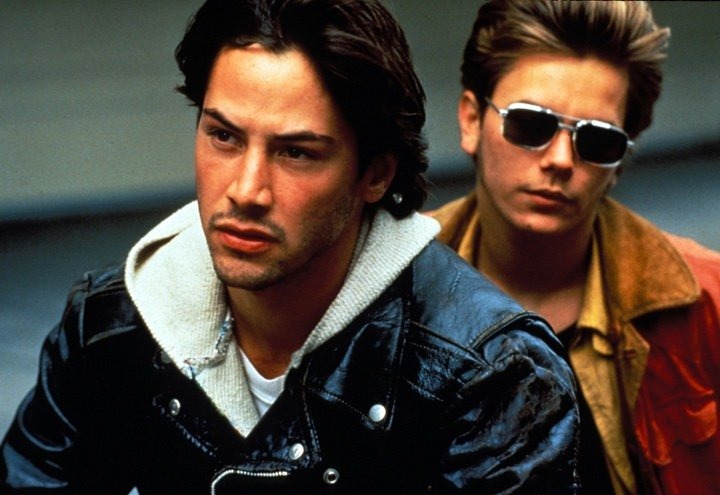

“Well, I don’t know. I mean… I mean, for me, I could love someone even if I, you know, wasn’t paid for it… I love you, and… you don’t pay me”. The American Dream, out of reach for those who this world would rather didn’t exist at all. It’s a constant search, along a road that will never end. “It probably goes all around the world.” River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves are Mike and Scott, two gay street hustlers, one on the search for his mother who exists only in his memories, the other searching for meaning in the world. My Own Private Idaho, a practically modern Shakespeare tale told with Gus Van Sant’s art-house sensibilities, was a benchmark for LGBT cinema.

River Phoenix, the original teen heartthrob who was gone from us far too soon, perfectly embodies the isolation and confusion of his position as a gay hustler. Having narcolepsy, Mike’s life is scattered with episodes that have him revisiting fragmental memories of his mother. It’s a brave performance, with Phoenix appearing vulnerable and offering a level of delicacy that most actors of his stature would be too afraid to attempt. Phoenix had ‘it’. The kind of ‘it’ that doesn’t exist until someone shows up with it. A range consisting of emotional devastation to casual charisma, Phoenix has it in a way that white actors in their early twenties have been chasing ever since. So few have it. No one has it like River did. I’m in love with his laugh when asked – when buying plane tickets – if he “has any baggage”, followed by his collected, yet sly, “Thanks”. River Phoenix here won’t just break your heart, he will shatter it.

My Own Private Idaho, a practically modern Shakespeare tale told with Gus Van Sant’s art-house sensibilities, was a benchmark for LGBT cinema

When paired with Keanu Reeves, the two are a revelation. Reeves, fresh faced here after his role in Bill & Ted, delivers each line like an alien trying to decipher what human communication looks and sounds like. Considering the script is based off Henry IV and Henry V, it’s perfect for the Shakespearean angle the film holds, and a perfect characteristic of a young man whose father happens to be the mayor, and who could easily leave his lifestyle behind. To borrow from Jarvis Cocker and Pulp’s iconic Common People: “If you called your dad/he could stop it all…”. The famous campfire scene, which Phoenix allegedly wrote himself, the one that shifts the film from being almost about victims of circumstance to being about natural emotion, could easily exist in a film about heterosexual love, yet the way it is played here is so highly appropriate that it would be perverse to appear in any other story.

Gus Van Sant, a crucial director of the American independent scene of the 1990s, directs in a fascinating way. Appearing with total control of the picture, he highlights the loneliness of Mike, often framing Phoenix completely alone in his own frame, at a distance from others. A sequence in Rome sees Phoenix shot with a longer lens, utterly detaching him from his surroundings. A straight cut to a wide shot picturing him all alone is a devastating exclamation mark. Van Sant’s approach to the world Mike and Scott inhabit is also a fantastic choice. Taking moments away from the two to explore the other hustlers present, these men are framed in an almost interview/documentary style as they recall and explain memories and anecdotes of past experiences. It’s an insightful, yet never derogatory approach, lending a level of realism to the poetry examined through uses of snippets of Mike’s childhood memories and time lapses of nature and the passing sky. It’s these little details of the passing sky though time lapses – and, of course, *that* shot of a barn crashing from the sky – that lends an avant-garde quality to proceedings, allowing us to see not only the world the way Mike sees it, but also how he sees himself within it. It’s also a form that pretentious independent filmmakers and annoying film studies kids have been trying to mimic since, unaware that they lack the nuance of Van Sant and the poignancy of River Phoenix.

My Own Private Idaho is the height of American independent cinema and essential to the ‘New Queer Cinema’ canon

A daring choice to frame a kiss shared between a heterosexual couple as distasteful, as if to reverse the ugly heteronormative response of the world, is truly compelling. The presentation of the sex scenes, something American cinema has always, to an extent, been rather prudish about, is captivating. Van Sant chooses to direct the actors as if they are completely still in various positions. They are human sculptures, works of art. Freeze frames could so easily have been used here, and perhaps a lesser filmmaker would have, yet Van Sant keeps it at 24 frames per second. It is not once derogatory or gratuitous.

My Own Private Idaho debuted at the Venice International Film Festival in 1991. It received critical acclaim and ushered in an era of ‘New Queer Cinema’. Praise was particularly aimed at Phoenix, and the James Dean comparisons were inevitable. It is the height of American independent cinema and essential to the ‘New Queer Cinema’ canon. The films of Todd Haynes and Greg Araki, too, are worth seeking out.

Comments