Has ‘entertainment news’ really taken over?

Roger Graef, a documentary maker, has said that the news has turned into entertainment. In the brutal battle for ratings, news stories that appeal to the masses, that excite us and sate our lust for conflict and controversy, have risen to the fore. He posits that we don’t hear about the particulars that build the key to any democracy: a well-informed electorate.

This seems like a reasonable assertion, and it is useful to look into the reasons behind it. Much has been made in the past few years of our shortened attention spans, of the millennial generation’s entitlement and globalisation’s destructive wake. We are all worried about the future, each and every one of us. It’s understandable to worry about tomorrow. A lot of this is to do with what we know, or rather, think we know about the world, and those assumptions are shaped by our news intake.

First of all, it is essential that we understand that the television industry is unequivocally ratings-driven. It is the vestige of the privatisation of the airwaves, as well as of what we, as a society, have demanded of the magic box for decades. The Only Way is Essex is not something that was wantonly shoved down our throats: it is the programming the public (a group which none of us can reasonably exclude ourselves from) desired.

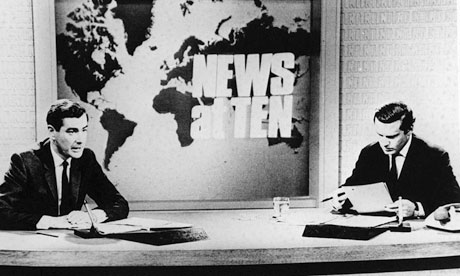

The news is an integral part of our every waking moment

We do want to know what’s going on in the world. We want to know as much as possible. This is why so many people stay constantly attuned to one of many 24-hour news sources. The news no longer merely occupies an hour during the evening; it is an integral part of our every waking moment.

A recent opinion column in The Guardian has delved into the meaning of this ceaseless stream of supposedly vital information. It argues that television as an industry has fully devolved into an entertainment service posing as an informative one. It says that negative news garners better ratings, so our news providers give it to us. We hear about epidemics, natural disasters, terrorist attacks, unemployment, death and destruction not more than they occur, but certainly not in the context in which they occur.

This leads us to be more concerned than we should be; this has caused social divisions to proliferate. Another reason behind the increased coverage of “easy headlines” and novelty figures is that people are inevitably attracted to areas in which they already have some previous knowledge. Much like how the ‘Leader of the Free World’ will not read a full document if his name is not included multiple times, we don’t want to hear about things we don’t know, haven’t heard of, or simply cannot fathom.

Negative news garners better ratings, so our news providers give it to us

There is no simple solution to this issue because simple solutions are rare. They exist only when a single entity can fix the problem, and this is not one of those cases. It’s easy to blame the media because big targets have always been the easiest to hit. But the media functions this way because it is what we have proven to want. If we demonstrate that we desire better, more relevant, contextualised news, and demand that television and other outlets give it to us, then I would be very surprised if we should fail. As usual, only through concerted, communal action can change be affected.

Comments