Bigger than Boxing, larger than life: a tribute to the greatest

“The greatest boxer? Give that to some boxer. Muhammad Ali was one of the greatest human beings that I’ve ever met in my life.”

It was only fitting that on the morning after Muhammad Ali passed away, succumbing to illness at the age of 74, the most poignant eulogy of all came from the man he felled in his most famous fight. George Foreman, who lost to Ali in the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, put it perfectly. To call Ali a boxer would be an understatement. To simply label him a great fighter would be doing him a disservice. Ali was a cultural icon – not just a legendary athlete, but a legendary man.

To call Ali a boxer would be an understatement. To simply label him a great fighter would be doing him a disservice. Ali was a cultural icon.

Humble beginnings set the stage for a glittering career. Who would have known that the theft of a red and white Schwinn bike on an autumn day in Louisville, Kentucky, would leave such an indelible mark on history. Ali, then a thin, hyperactive 12-year-old named Cassius Clay, headed to a local black merchant’s convention in search of free sweets and popcorn. Clumsy in his youthful zeal, he left the dazzling bike outside, where it vanished. Amidst floods of angry tears, the young boy was introduced to a police officer in the basement of the building named Joe Martin, promising to “whup” the culprit. Martin took one quick look at Clay and asked “do you know how to fight?”. “No, but I’d fight anyway”, Clay answered. He’d lost his bike, but in a moment of destiny he had found his calling. Then and there, Clay took up Martin’s offer to teach him how to box and his ascent to greatness began.

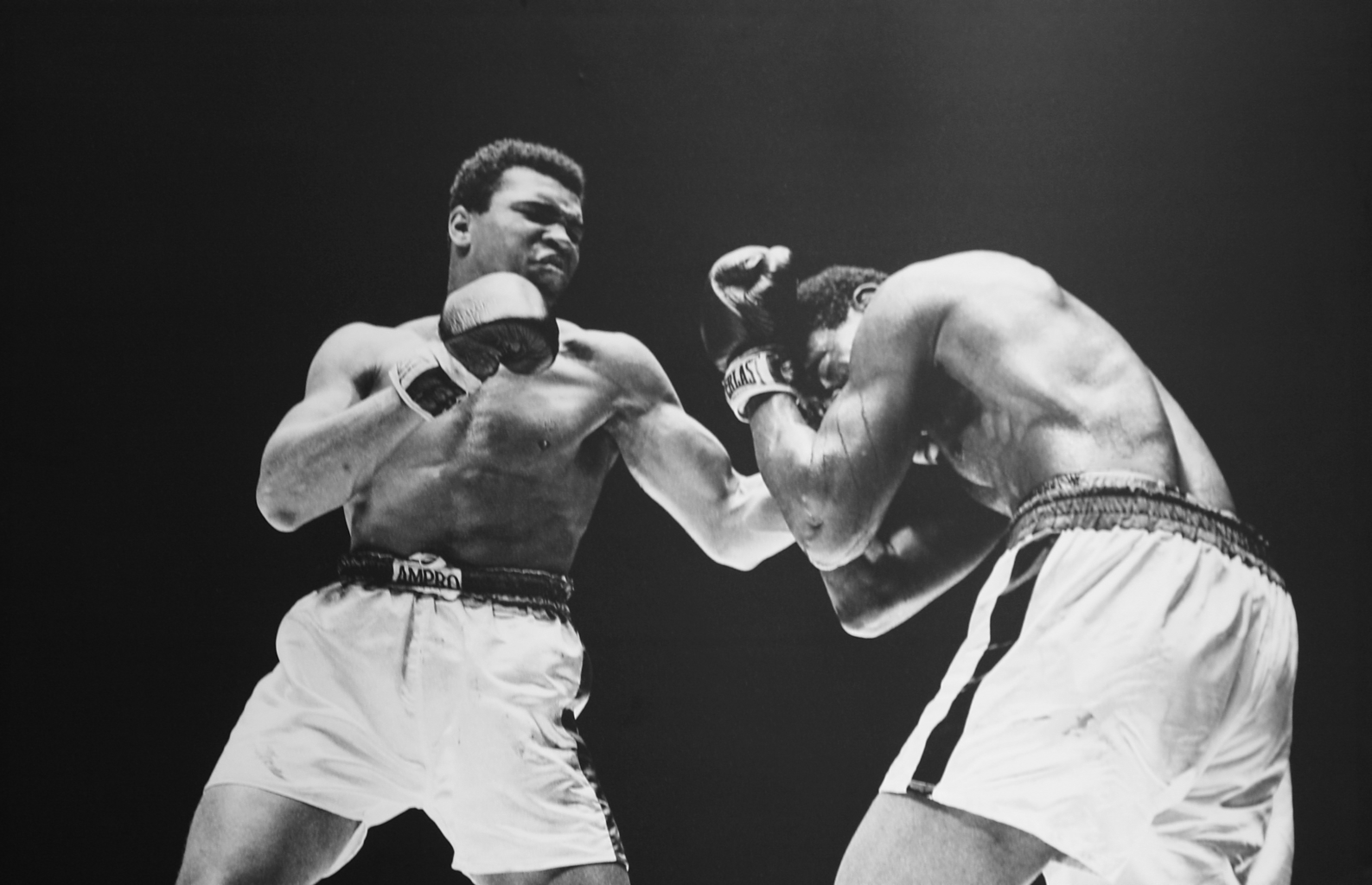

As he grew from a rangy teenager into a lean, slick, physical specimen, Ali’s once in a generation talent became strikingly apparent. He didn’t plod around the ring like traditional heavyweight fighters, he floated. Behind the gift of his slender physique, he turned boxing into ballet. He won bout after bout, transforming the savage fight game into an art form like nobody before him. At just 18, he finished off his amateur career with a flourish, claiming an Olympic gold medal at the 1960 Games in Rome. Upon turning pro, he compiled a string of wins as a professional on his way to shocking the most fearsome man boxing had ever seen, Sonny Liston, for his first championship in 1964, completing a meteoric rise to stardom.

As his career progressed, something extraordinary happened. The world realised this brash, beautiful young man with a penchant for talking trash and ruffling feathers was beyond boxing. Ali’s antics became stuff of legend. He wouldn’t just embarrass opponents, he would predict the round he would knock them out. He would write poetry and scream to anybody who would listen: “I am the greatest!”. These affirmations of his ability and stirring displays of self belief rattled many traditionalists. Never before in the modern era had a black athlete been so publicly self-assured. Ali put it best:

“I am America. I am the part you won’t recognise. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me.”

He took us to a realm of sporting theatre nobody else could.

Behind the bravado Ali would take his sport into the stratosphere. His contests were global spectacles; not just moments, but myths. He once decreed “I am bigger than boxing, I am bigger than all the champions put together. I am bigger than the Superbowl, the Rosebowl, the Kentucky Derby, The Indy 500, when I go, the world listens”. He wasn’t wrong. Be it bringing the world to a standstill in the ‘Fight of the Century’ against his arch-nemesis Joe Frazier, rumbling in the jungle against George Foreman with the whole of Zaire screaming “Ali Bomaye!”, or thrilling us in Manila while knocking on death’s door in sweltering Filipino heat to halt Frazier one last time; he took us to a realm of sporting theatre nobody else could.

You always got the sense, however, that the bulk of Ali’s historical impact would lie beyond the ropes. In the shadow of the oppressive Jim Crow laws, against the backdrop of the protracted civil rights struggle, here, under the microscope was a black man unwilling to bend. With his feats inside the ring and his words outside of it, Ali strived to prove his people were equal, at the very least, to their white counterparts. His conversion to Islam shortly after winning the championship and active engagement in the civil rights struggle as a member of The Nation of Islam was the ultimate demonstration of defiance. Freeing himself from the shackles of a slave name, he showed he was unafraid to take control of his destiny, to think for himself and challenge the establishment with his position as the most lauded athlete in the world, his leverage and faith as the focal point.

The defining moment in his legend, his refusal to be drafted into the U.S. Army to fight in the Vietnam War in 1967, spawned his most powerful sound bite:

“My conscience wont let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father. Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Stripped of his title at the peak of his powers, he had made a huge sacrifice in order to hold the U.S. government to account; a reminder that his thirst for justice was even more important to him than the sport he devoted his life to.

His once booming voice was left little more than a whisper, but even then his presence still spoke volumes.

With a legacy that stretched far beyond the fleet-footed steps he took in his white Everlast boxing boots, Ali continued to make a cultural impact that not even sickness could dampen long after his retirement in 1981. Paying the price for his courage in the ring over the course of 21 long, hard years, Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Syndrome in 1984. Those wonderful features, once so expressive, were replaced by a mask, his once booming voice was left little more than a whisper, but even then his presence still spoke volumes. Ali’s appearance at global events, including lighting the Olympic torch in 1996 despite noticeable tremors, and his dedication to philanthropic causes until Parkinson’s made it physically impossible, provided further proof of his unwavering desire to do good.

Be it young fighters channelling their best impressions, politicians and activists fighting the case of conscientious objection or writers like myself trying their best to find words to pay homage to his life, “the greatest” shall surely live forever.

Comments