What UK-China ties reveal about our place in the world economy

Today’s geopolitical climate is a stormy one for the UK, with many an ominous cloud on the horizon. With the UK falling out with the US and detached from the EU, safe havens seem difficult to come by. Or more accurately, the UK is being increasingly pressured to set a single heading, to commit itself to one direction or the other.

Already, the UK has been placed in awkward positions of divided allegiance. The Greenland crisis forced Prime Minister Keir Starmer to cast his stone, committing (though not as powerfully as other European allies) to defending the “fundamental” right that “any decision about the future status of Greenland belongs to the people of Greenland and the Kingdom of Denmark alone.”

With the US president foreshadowing future economic warfare even against close allies, it would be remiss of the UK not to organise contingencies in the form of strengthened economic ties with more reliable allies, as well as potentially shopping for a new ally or two

Though a great deal of the tension over Greenland has eased after Trump promised “[he] won’t use force” to acquire the territory, he showed very little restraint in easing his administration’s tariff policies, reasserting that the US had been economically exploited by the rest of the world. With the US president foreshadowing future economic warfare even against close allies, it would be remiss of the UK not to organise contingencies in the form of strengthened economic ties with more reliable allies, as well as potentially shopping for a new ally or two.

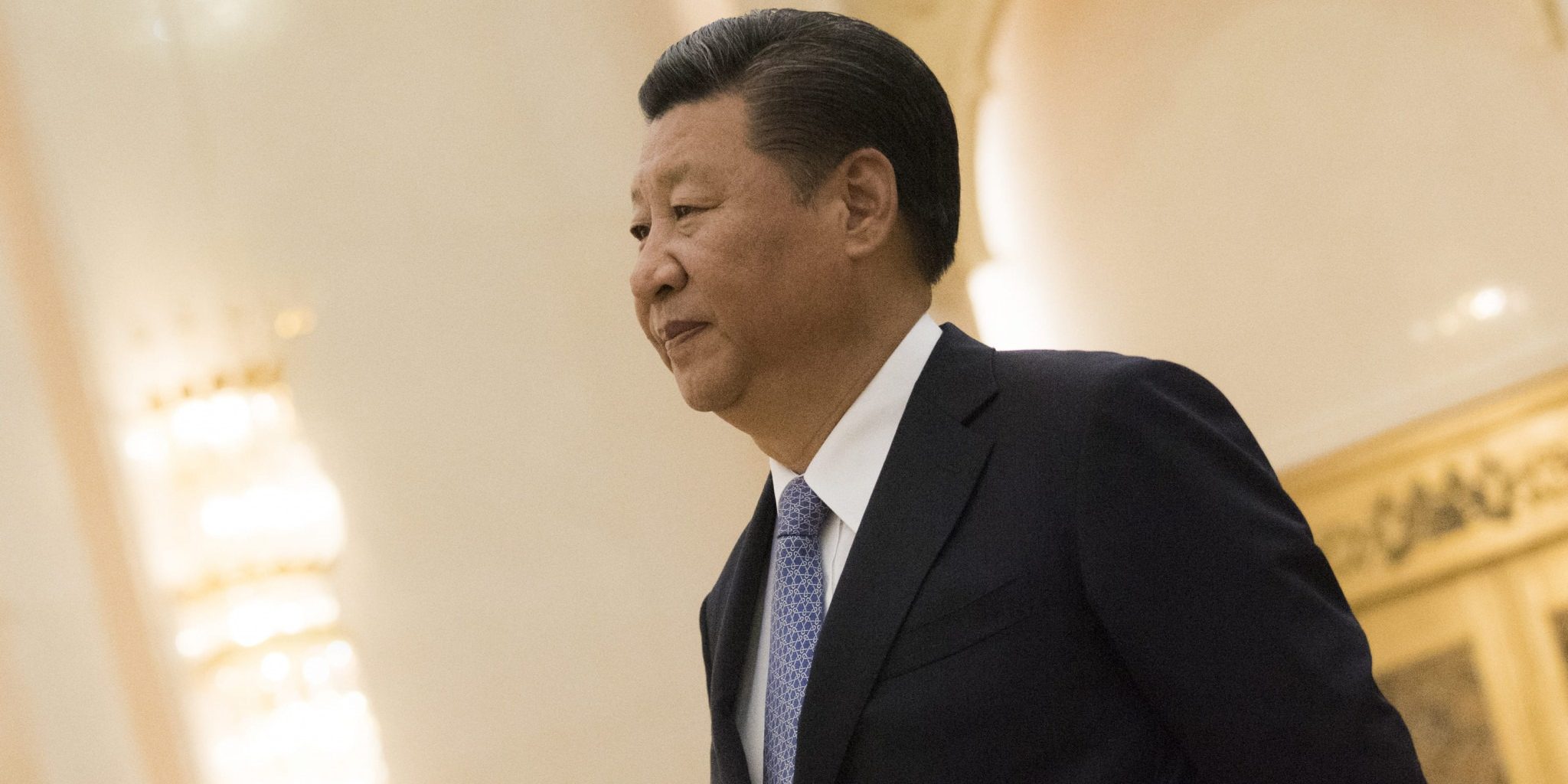

Fortunately, that appears to be exactly what Prime Minister Keir Starmer is doing. He landed in China on January 27, accompanied by a delegation of nearly 60 businesses, to discuss closer business ties with China over a variety of sectors. Being the first prime minister to visit China since Theresa May in 2018, the visit represents a turning point in UK-China relations, and Starmer has promised a “consistent, pragmatic partnership with China, to make the UK better off.

Between September 2024 and September 2025, China was the UK’s fifth-largest trading partner, and total UK exports to China in that period saw a decrease of 22% from the previous economic year, according to the latest statistics on trade between the UK and China. Now, China has risen to take the position of third-largest trading partner to the UK; closer economic ties with China have been brewing since at least March 2025, and were intensifying in November 2025, with the first official talks between the two countries in seven years.

The Prime Minister maintains the rhetorical semblance of autonomy in stating that “a strategic and consistent relationship with them is firmly in our national interest,” which eludes the necessity to mention that it may be the UK’s only option

However, though closer ties with China may represent an economic victory, they paint a picture of a UK so desperate for allies that it binds itself to a country that has been labelled by many as a national security threat. The swathes of evidence held by the government universally depicting China as a threat suggest that China is an unavoidable trading partner, and that choosing not to engage with them is a luxury the UK does not have.

The Prime Minister maintains the rhetorical semblance of autonomy in stating that “a strategic and consistent relationship with them is firmly in our national interest,” which eludes the necessity to mention that it may be the UK’s only option. In his press release on January 26, he commented that “we will not trade economic co-operation for our national security” and that “we will raise the areas where we disagree with China,” which seems like a difficult promise to deliver on.

Additionally, the government is far from unaware of China’s appalling human rights record, having reported in 2023 that “there continued to be widespread restrictions and violations on human rights and fundamental freedoms across China in 2022,” including “systematic human rights violations in Xinjiang.” Though the UK is hardly in a position to be picky about its trading partners, it is undeniable that China represents both a security liability and an ethical violation of what the UK claims to stand for.

Ultimately, though trade with China may very well represent a saving grace for the UK in the future, it is discouraging that it represents our most optimistic option for economic stability

We are unlikely to ever hear any acknowledgement of China’s human rights violations, partly from a desire of the government to avoid public outcry over closer ties with China, and partly from a desire of China to repress research into their very shady record, which they have shown very little aversion to doing, secretly or not.

Ultimately, though trade with China may very well represent a saving grace for the UK in the future, it is discouraging that it represents our most optimistic option for economic stability.

In conjunction, the prime minister’s attempts at economically reintegrating the UK into the EU, such as re-entering the UK into the Erasmus+ programme, accompanying food and drink trade deals, and exploratory talks on entering the EU’s internal electricity market, imply a wisely cautious approach to US economic antagonisms.

Whether these strengthened economic bonds will prove robust enough to weather unpredictable US trading behaviours remains to be seen. The US currently represents the UK’s single greatest trading partner, accounting for 17.5% of total UK trade from September 2024 to September 2025 – should this market turn towards isolationism, the UK will undoubtedly suffer. In such a hypothetical, it is only a question of how much.

I can only hope that a closer economic partnership with China proves itself to be worthwhile, regardless of my numerous reservations. Its position as the UK’s greatest hope to withstand potential future economic instability does imply a UK without sufficient economic connections to thrive without the US.

Comments