Is war good for the economy?

From the tribal skirmishes of Mesopotamia to the mechanised slaughter of the World Wars and the algorithmic precision of drone warfare today, war has remained a constant force in human history. The nature of warfare has changed drastically over time, becoming more organised, deadlier in its weaponry, more technologically advanced, and more deeply woven into the fabric of the modern state. In some cases, war has left behind more than destruction. The Hundred Years’ War, for instance, helped shape the fiscal institutions that define modern nation-states. In the industrial era, imperial expansion forged lasting ties between governments and private arms manufacturers, laying the groundwork for what would later be known as the military-industrial complex.

Across this long and changing history, one idea keeps coming back: that war, despite its destruction, can help stimulate economic growth. But is that claim grounded in history, or is it a myth disguised by exceptional circumstances? As the war in Ukraine continues, and conflicts across the Middle East and elsewhere grow more unstable, this question feels more relevant than ever.

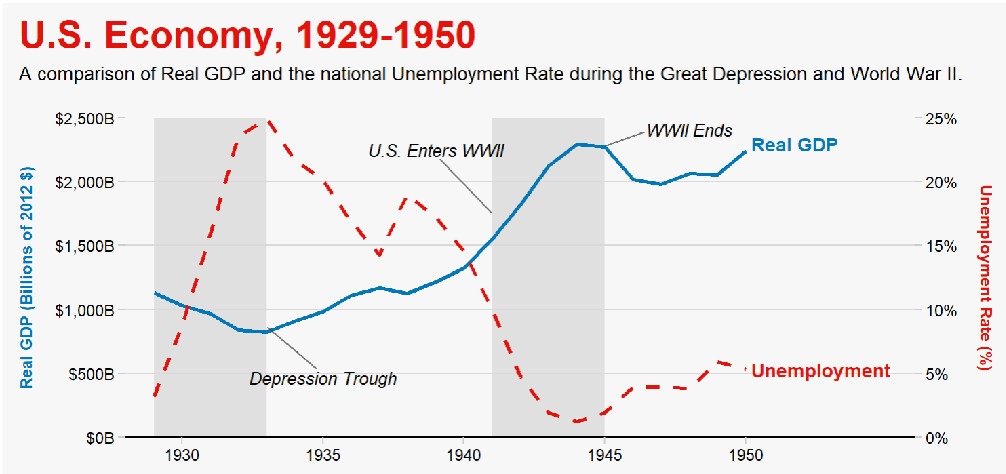

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Author’s compilation from official data.

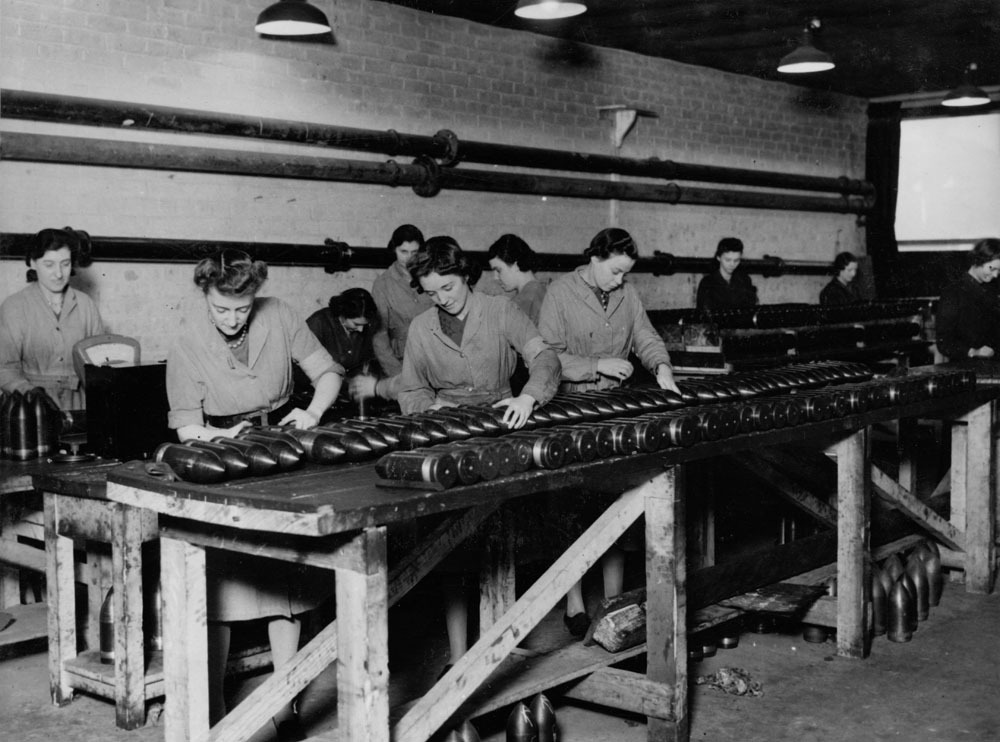

For many, the strongest argument that war can boost economic growth comes from the United States during the Second World War. After a decade of crippling depression, the American economy bounced back to life. As shown in the graph above, real GDP more than doubled between 1940 and 1945. Unemployment, stuck in double digits throughout the 1930s, dropped to just over 1% by 1944 – the lowest rate ever recorded. Civilian industries shifted to war production, federal spending soared, and the labour market tightened to the point where women and previously excluded groups were pulled into the workforce. For a country still reeling from the Great Depression, the wartime economy looked like a full-scale revival.

The benefits weren’t just macroeconomic. Wartime urgency drove a wave of technological breakthroughs that would shape the post-war world. Advances in radar, jet engines, computing, medicine, and synthetic materials were direct results of military research and industrial scale-up. But above all, the war seemed to prove a growing idea in economics. To many at the time, this was Keynesianism playing out in real time: large-scale government spending, financed by deficits, had pulled the economy out of depression and pushed it into full employment. It all seemed to confirm the Keynesian logic of wartime prosperity, and why wouldn’t it? The numbers spoke for themselves.

However, a deeper investigation into the wartime economy, the methods of its financing, and the actual living standards of the civilian population reveals a far more troubling picture.

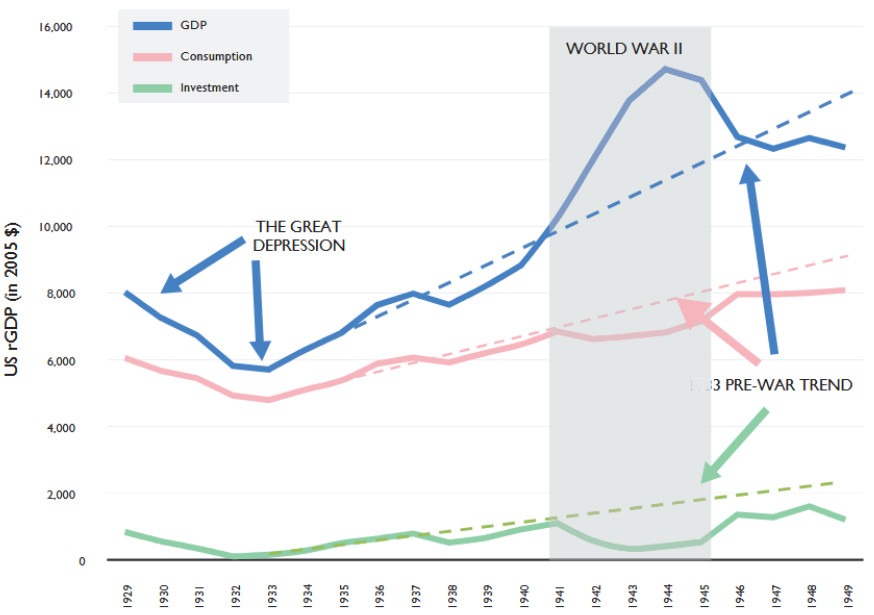

Source: Institute for Economics and Peace.

As the graph above shows, real GDP surged during World War II, but this growth didn’t translate into broad-based prosperity. Both private consumption and investment lagged well behind their prewar trajectories, suggesting that much of the boom came from government-driven military output rather than improvements in civilian living standards. In fact, private consumption per person was lower during the war than it had been in 1940, even before accounting for rationing and quality deterioration.

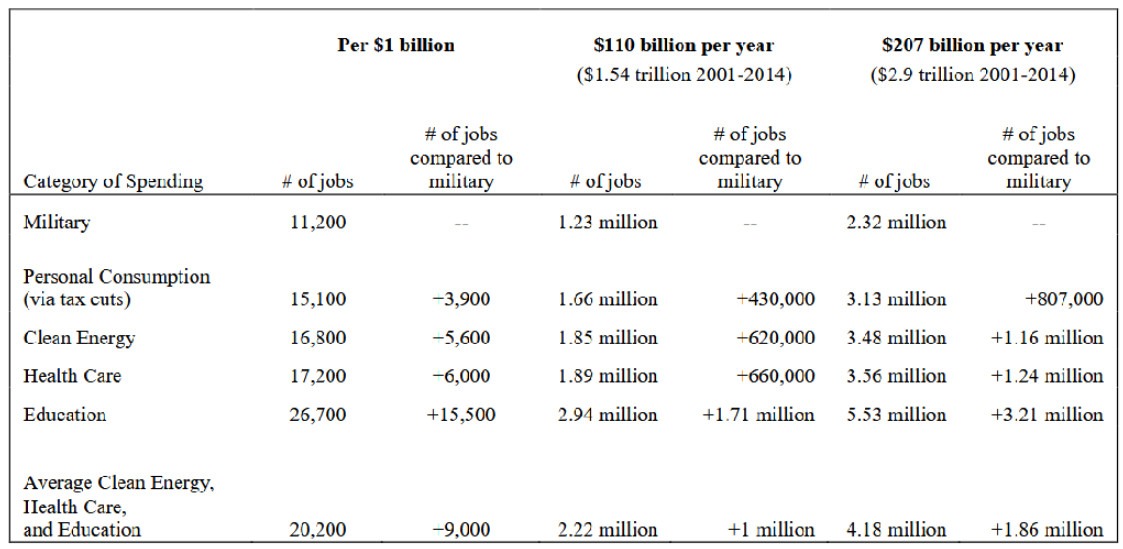

The Costs of War Project found that military spending consistently created fewer jobs than comparable investments in sectors like education and healthcare

Economists have long questioned the efficiency of this kind of growth. Robert Barro’s seminal 1981 study estimated a fiscal multiplier between 0.6 and 0.8 for WWII, meaning every dollar of military spending boosted GDP by less than a dollar. More recent state-level estimates like those by Brunet (2024) find multipliers as low as 0.25. In other words, much of the wartime economic expansion came at the expense of private sector output.

Even if wartime production lifted headline GDP, it came at enormous opportunity costs. The same labour, capital, and industrial capacity used to build tanks, ships, and ammunition could have gone toward housing, infrastructure, schools, or consumer goods. The domestic economy, meanwhile, bore the weight of this shift: rationing and price controls were widespread, with Americans queuing for essentials like meat, gasoline, and shoes. War borrowing also surged, with the national debt more than doubling relative to GDP during the conflict.

Source: Costs of War Project, Brown University.

Later research has shown that this kind of tradeoff persists in the conflicts of the 21st century. For instance, a study of post-2001 U.S. wars by the Costs of War Project found that military spending consistently created fewer jobs than comparable investments in sectors like education and healthcare. In other words, while war spending may raise output, it tends to do so by diverting resources from parts of the economy that tend to offer greater social and economic returns.

Furthermore, wars rarely confine their costs to the battlefield. The countries where fighting actually happens are hit the hardest, no doubt – cities are destroyed, people are displaced, and economic activity collapses. But the effects almost always spill over. A recent study by Federle et al. (2024), which analyses the macroeconomic fallout of all major wars since 1870, shows that neighbouring countries often suffer significant spillovers even when the war occurs entirely outside their borders. These include trade slowdowns, disrupted supply chains, rising inflation, and higher input costs. The war in Ukraine is a clear example: although most of Europe wasn’t directly involved, it still faced energy shortages, price spikes, and tighter interest rates as central banks reacted.

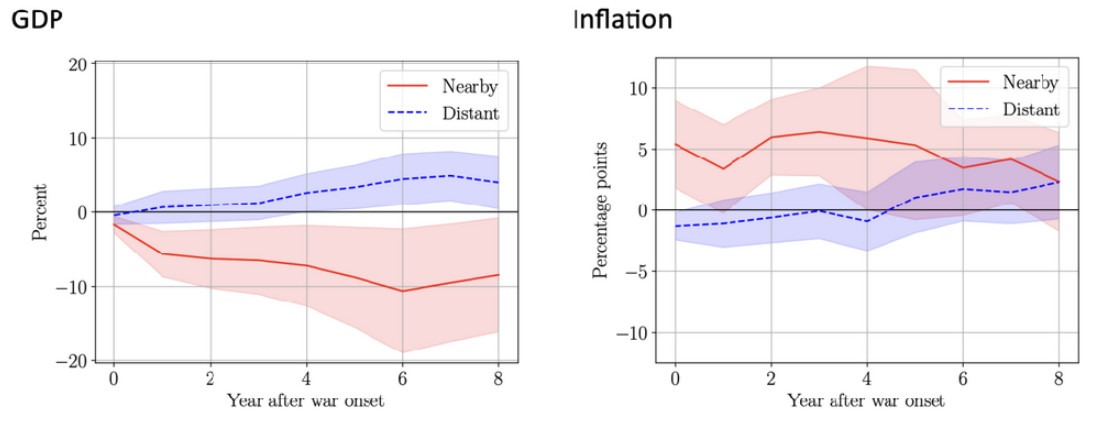

The Economic Repercussions in Nearby vs Distant Countries

Notes: The figure shows how GDP and inflation adjust in response to the start of war in nearby (solid red line) and distant (blue dashed line) countries. The left panel shows the percentage deviation of GDP from trend; the right panel shows the deviation of inflation from the prewar rate, in percentage points. Shaded areas denote 90% confidence bounds. Source: Federle et al. (2024).

At the same time, countries geographically distant from the conflict can sometimes experience the opposite: mild or even positive short-term effects. If global military demand rises, they may benefit from increased production without suffering the physical toll. The United States during World War II was precisely one such case. The war did not come to American soil, which meant that its industries could expand without having to rebuild anything. But that kind of geographic advantage is rare.

In most cases, countries close to a conflict end up absorbing a good chunk of the cost. The same study shows that nearby economies, on average, saw their GDP fall nearly 10% below trend within five years of a war starting. Inflation also climbed and stayed elevated.

War is not an engine of prosperity. It is, at its core, an enterprise of destruction. The illusion of economic growth it creates is built on scarcity, distortion, and sacrifice, mistaken for progress. And when the dust finally settles, what remains is not wealth but wreckage: broken infrastructure, warped priorities, and generations left to carry the cost. True prosperity doesn’t come from mobilising for war. It comes from building peace. If economics teaches us anything about war, it’s this: the most powerful strategy for growth isn’t conquest. It’s creation.

Comments (2)

Very well written, Shreyas! This article does a great job of deconstructing the myth that war is good for the economy. It’s a powerful reminder that while headlines might show a GDP boom during wartime, the reality for most people is scarcity and sacrifice. The distinction between military output and genuine prosperity is a crucial one that’s often overlooked.

Amazing article. A refreshing take on costs of war