What Reform reveals

Famed literary critic and professor Edward Said once wrote that “no one today is purely one thing.” Said suggested that our collective identities are not fixed markers, but instead “no more than starting points”. He noted that the old European empires, while consolidating a mixture of cultures and identities, forced the view that people were exclusively one culture and identity. Over time, the forces of change, and their own contradictions, made these empires disappear. Now, we live in a world where their ghosts haunt societies that look (and are) very different.

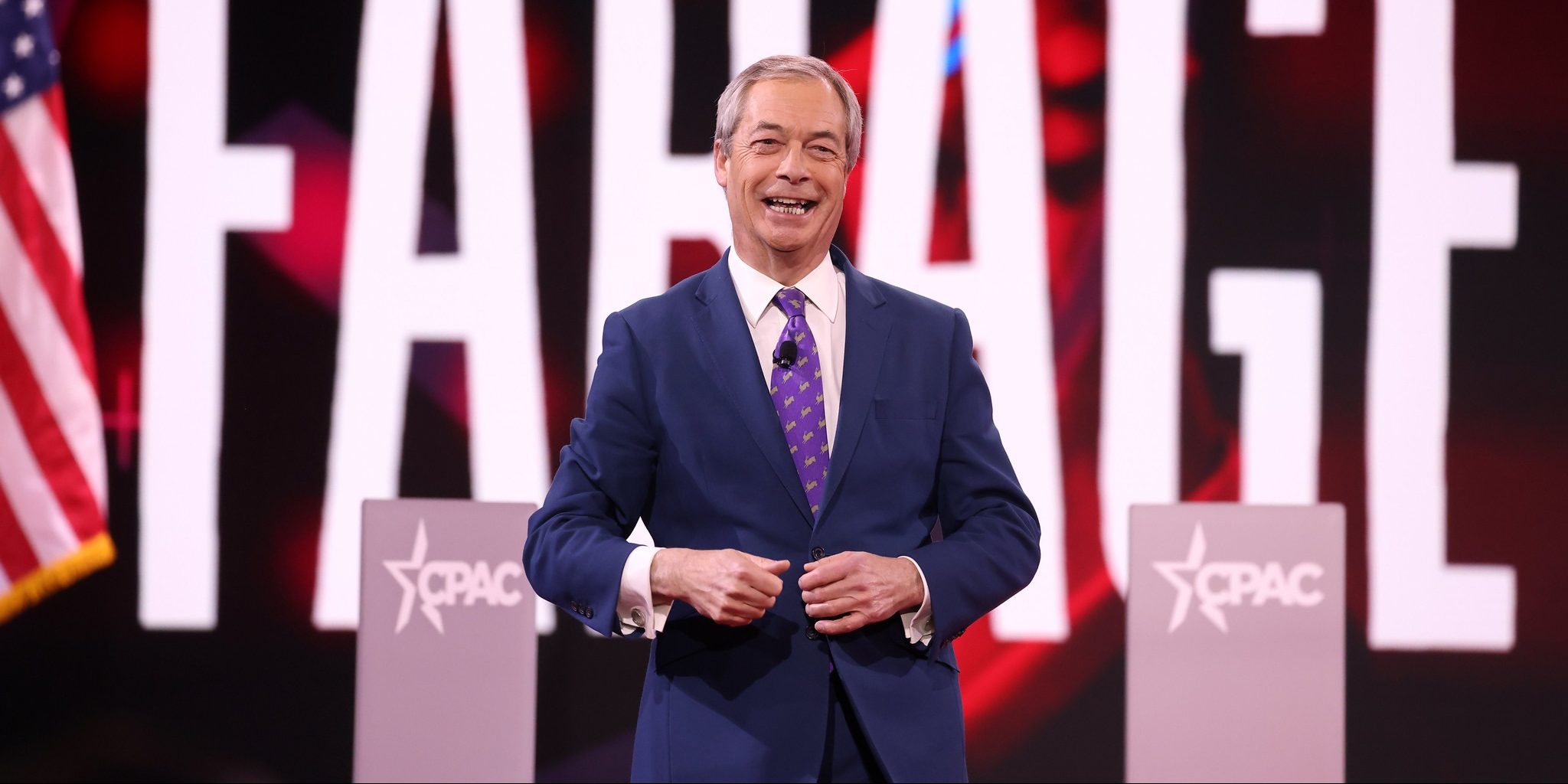

Reform UK, Nigel Farage’s unabashedly nationalist party, longs to live in this terrible paradox again, bringing the imperial mantra back home to a post-imperial society. For Farage, Britain is one total thing, or it is nothing at all. They unfurl a nationalism which, like many that have come before it, rejects that Britain has had anything other than a grand organic ascent, only broken down by malignant, subversive, foreign forces from within. The most common response I’ve seen to Reform UK: a confused, stunned shock. Why, in a multicultural society, does this ideology come about and persist in vast swathes of the country? How can working people, who elected past and present Labour governments, suddenly spout out Reform’s accusations of “two-tier Kier” or that Britain is in a state of “societal collapse” because of mass immigration? The answer is history.

Mosely remained a constant presence in British politics right up until the late ’60s

Former Home Secretary Alan Johnson grew up in grinding, awful poverty. Orphaned, and raised by his sister, he was often regarded as the true face of the working class in Blair’s government. In his memoir This Boy: A Memoir of Childhood, Johnson recalls the racial tension that was boiling over in Notting Hill, where he grew up, in 1958. After the murder of a local Antiguan carpenter, Kelso Cochrane, by a gang of what Johnson’s mother described as “white Teddy boys”, a certain aristocrat chose to stand in North Kensington for the general election. This man was Oswald Mosely.

Coming back from self-imposed exile in France, after being interned during the war for leading the British Union of Fascists (BUF), Mosely saw a ripe opportunity to stir up racial hatred in Johnson’s working-class community. Holding his meetings on the very spot where Kelso was killed, he warned the white community – most of whom were living in overcrowded squalor – that it was the new wave of Afro-Caribbean immigrants who, seemingly, had the power to destroy their lives, their new society, and the small gains of the NHS and the welfare state created by the Labour government after the war. He didn’t win the election, but Mosely remained a constant presence in British politics right up until the late ’60s. The men who murdered Kelso Cochrane have never been brought to justice to this day. Before the war, Mosely had organised young working-class men to be his Blackshirts, the paramilitary wing of BUF. The playwright Harold Pinter recalled how they would attack him and other young East End Jewish kids, even beating up older rabbis on the Sabbath. All these events occurred not even a century ago.

The core truth is that Reform UK thrives on people’s insecurity

Another story, perhaps one more familiar, is that on 20 April 1988, the Conservative MP and Shadow Secretary of State for Defence addressed the general meeting of the West Midlands Area Conservative Political Centre in Birmingham. He claimed that white, Anglo-Saxon British people were being made “strangers in their own country”, fearing that the new Race Relations Bill would make the “native English” population persecuted minorities. Enoch Powell was widely condemned for his now infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. And yet, after his sacking from the shadow cabinet, 1,000 London dockers went on strike in support of Powell. A day later, 600 dockers at St. Katharine Docks voted to strike and numerous smaller factories across the country followed. Many older people in the Midlands, North West, and elsewhere still speak of nostalgia for that moment of “Powell for PM”, and solidarity for the racist reactionary.

If these stories tell us anything, it is this: Nationalism is normal. Not what some on the left and the right may say: that Reform UK is a bizarre aberration, a foreign populist import, or a cynical front for billionaires. All these theories are partly true, but they are not the core truth. The core truth is that Reform UK thrives on people’s insecurity. Self-doubt over dignity, ability, economic control in their lives, and, above all, identity are the fears that Reform feeds off like maggots. Working class communities are susceptible to such insecurity because they already have a dozen other insecurities on their backs. However, though many middle-class people will not be on the streets in anti-immigrant marches, it does not mean they are not speaking it in whispers and ‘polite’ bigoted talk. It is no coincidence that Mosley, Powell and Farage all came from comfortable upper class or upper middle-class backgrounds. All were educated at public schools.

It’s very easy, coming from a background of wealth, security, and ignorance, to say ‘I’d give my life for my country’

Why has this insecurity become so widespread? The reasons go back over a century. Brexit was certainly a warning sign, with many so insecure in what it meant to be ‘British’ that many English people chose to, essentially, economically shoot the country in the foot. A lot of this is to do with the stories that ‘Britain’ has told itself. Once, many people in these islands saw Britain as a fortress. At the time, this self-perception was true, Britain being an empire that spanned half the earth. But that was a hundred years ago.

Maybe it’s because I’m from Northern Ireland, where we went through a conflict where rival armies declared that their nation was under attack, that if democratic rights were to be suppressed, students were to be shot in the street, and children would have to be bombed, then that would be the cost for a free nation. I cringe sometimes hearing the leaders of Reform UK spouting off militaristic language. It’s very easy, coming from a background of wealth, security, and ignorance, to say “I’d give my life for my country”. To tie your political organisation with the ‘community’ sets a dangerous precedent, particularly if you’re suggesting sending people to penal colonies as a potential justice policy, as Farage has recently said.

I remember my mum telling me about the time when she was 10 and saw Enoch Powell on the television. Powell, running for the South Down seat in 1983 for the Ulster Unionist Party, said bluntly “There are no Irish people in my constituency.” She looked back to her dad and said, simply, he was wrong. They were both Irish citizens living in his constituency. I imagine the same observation is being made by 10-year-olds, and even younger children, in the homes of immigrant families all the across the UK. Hearing adult men and women say that they are a threat to the nation and that they do not belong. Those children turning to their parents and speaking truth to power.

Comments