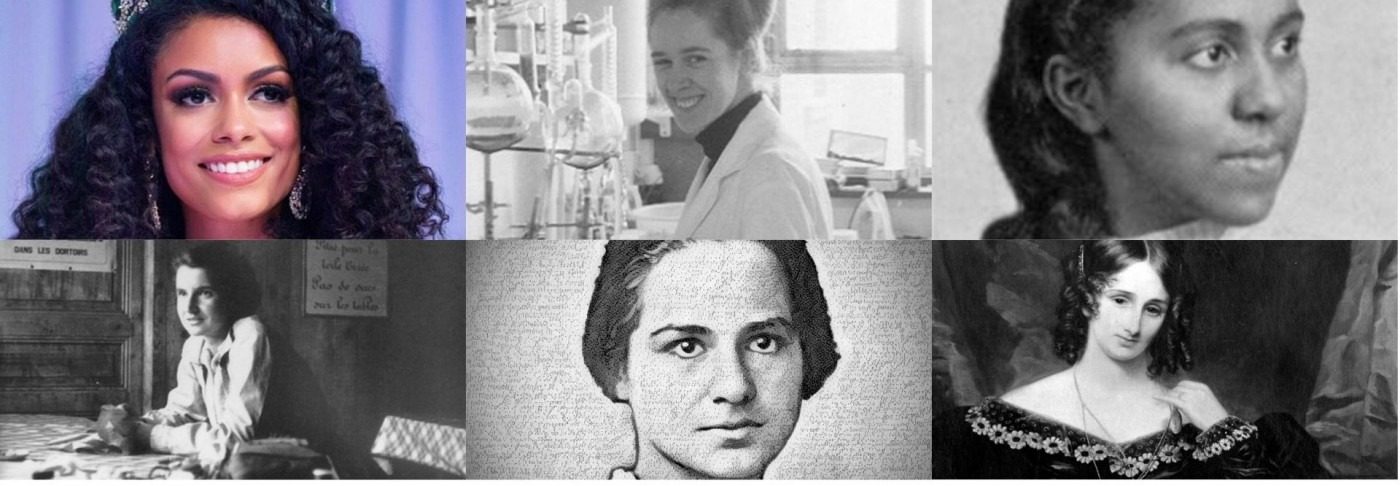

International Women’s Day: six female trailblazers in STEM

To mark International Women’s Day, six of our writers celebrate women in the world of science, technology, engineering and mathematics that inspire them.

Fionnghuala O’Reilly – Anna Bickerton

Sharp, savvy and brilliantly articulate, Fionnghuala ‘Fig’ O’Reilly has made her mark in all things data science, media… and beauty pageantry? If winning Miss Universe Ireland – the country’s first woman of colour to hold the title – wasn’t enough for the 31-year-old to impress you, her experience as a NASA data analyst certainly will. The accomplished Irish American worked as one of the space agency’s ‘datanauts’, contributing to space missions by analysing data from satellite projects to support NASA’s exploration efforts and advance astronomical research.

Beyond space (although, perhaps disappointingly, not literally), O’Reilly has combined her passions for engineering and advocacy, making a formidable science communicator as a correspondent on CBS’ Emmy-nominated Mission Unstoppable, inspiring young girls to pursue STEM. She’s also launched Space to Reach, a networking program designed to support black women seeking careers in technology.

Jean Purdy – Abigail Mableson

There is nothing more empowering than the work of a female pioneer for women’s fertility, a title that British embryologist Jean Purdy rightfully deserves. Often considered the ‘forgotten IVF pioneer’ and overshadowed by her two male colleagues, Purdy was part of the team who developed the first ‘test tube baby’, named Louise Brown, in 1978. Throughout her life, Purdy’s groundbreaking work contributed to the conception of 500 babies, transforming laboratory research into life-changing fertility treatment in a time when infertility had no viable solution. She died from a malignant melanoma in 1985, at the young age of 39. Yet, her scientific legacy lives on in the six million babies conceived through IVF worldwide. It would be hard to think of a world without IVF, and we should be forever thankful for Purdy’s trailblazing work in making parenthood possible for so many families.

Marie Maynard Daly – Abhay Venkitaraman

The first African American woman to earn a Chemistry PhD, Dr. Marie Maynard Daly left an indelible mark on the world of biochemistry. After graduating from Queens College, Daly later went to Columbia University, where she studied under Mary Caldwell, the university’s first female assistant professor. Researching the role that pancreatic amylase plays in converting corn starch to sugar, Daly officially became Dr. Daly.

With a PhD under her belt, Daly pursued research with groundbreaking implications for human biology. Most famously, by testing on rats, she discovered a link between cholesterol and heart conditions such as hypertension and narrowed arteries. She also studied histones – proteins that comprise DNA – and the adverse impact of cigarettes on the heart and lungs.

She sought to advance equality, participating in a gathering of 30 minority ethnic women in science, leading to a report on their challenges, and created a 1988 scholarship to help African American science students at Queens.

Like many accomplished scientists from marginalised backgrounds, Daly is not a household name. One can only hope that our appreciation for her work blossoms in the years ahead.

Rosalind Franklin – Tom Ryan

Rosalind Franklin is arguably one of the most unsung heroes of, not just modern British science, but science as a whole, making revolutionary contributions that paved the way for Watson and Crick’s eventual building of a DNA model in 1953. Through her work in X-ray diffraction, Franklin demonstrated the double helix structure of the acid, showing that the molecule could exist in two forms.

Although her research was included in Watson and Crick’s pioneering paper in 1953, she was still always the “dark lady of DNA”. So while Franklin may have contributed to one of the most momentous scientific discoveries in history, according to Watson and Crick, it was the two men that had found “the secret of life”. A move from her academic position at King’s College London also meant she lost access to all her DNA photographs – and her research and discoveries were swiftly claimed by others: men. She died an untimely death aged only 37, a few years after her work was first published, and only then was her work finally celebrated.

Marietta Blau – Abishek Elavarasan

Marietta Blau was a particle physicist born in Vienna in 1894. Her contributions to the field significantly advanced the study of cosmic rays, transforming them from a natural phenomenon into a traceable source of information about the subatomic world. Before the physicist’s work, cosmic rays could only be counted discretely using a Geiger counter. Blau developed photographic emulsions made of silver halides in a gelatin matrix, which allowed the tracks of cosmic particles to be detected as they chemically reacted with the halides in the gelatin. From these tracks, the size, velocity, and other properties of particles could be derived, opening up a new paradigm of research.

Blau’s perseverance in her work is reflected in her personal life as well. Despite the challenges of studying in a male-dominated field in Vienna, she earned her doctorate and surpassed her peers at the Institute for Radium Research. When Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938, Blau, being Jewish, fled persecution with the help of Albert Einstein, finding refuge in Mexico. Much of her work was destroyed, and recognition for her contributions was delayed until after the war, when she was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1950.

Mary Shelley – Martin Day

Every bit a woman of towering historical stature, it’s undeniable that Mary Shelley was not actually a scientist. Frankenstein’s Monster, as the name suggests, was brought to life by the enigmatic Doctor Frankenstein – and crucially, neither of them actually existed. Not for nothing, however, is Shelley known as the ‘Mother of Science Fiction’: her novel Frankenstein was every bit as revolutionary as the foremost scientific advances of the 19th century, incorporating cutting-edge concepts as electricity and cadaver experimentation. Crucially, nothing like it had ever existed before, in exploring science, and not the supernatural, as the basis for fiction.

In the centuries since, sci-fi has grown to become a dominant genre in books, movies and television. What qualified Shelley to stand among these other trailblazers of science is the extent to which her genre has inspired countless generations of bright young minds. From the helicopter and the space rocket, to atomic power and the cellphone, dozens of key technological and scientific leaps were first dreamed up as stories. Inspiration is as essential to science as any research as any research, and it is Shelley, with her groundbreaking tale of an (early-)modern Prometheus, who can claim credit.

Comments