The rise of AI in academics: good, bad, or just outright unnecessary?

The first pro vice-chancellor for artificial intelligence, Shushma Patel, has been appointed in the UK at De Montfort University. The adoption of a senior university leader seems to represent a broader trend in academia which favours the integration of AI into university curriculums.

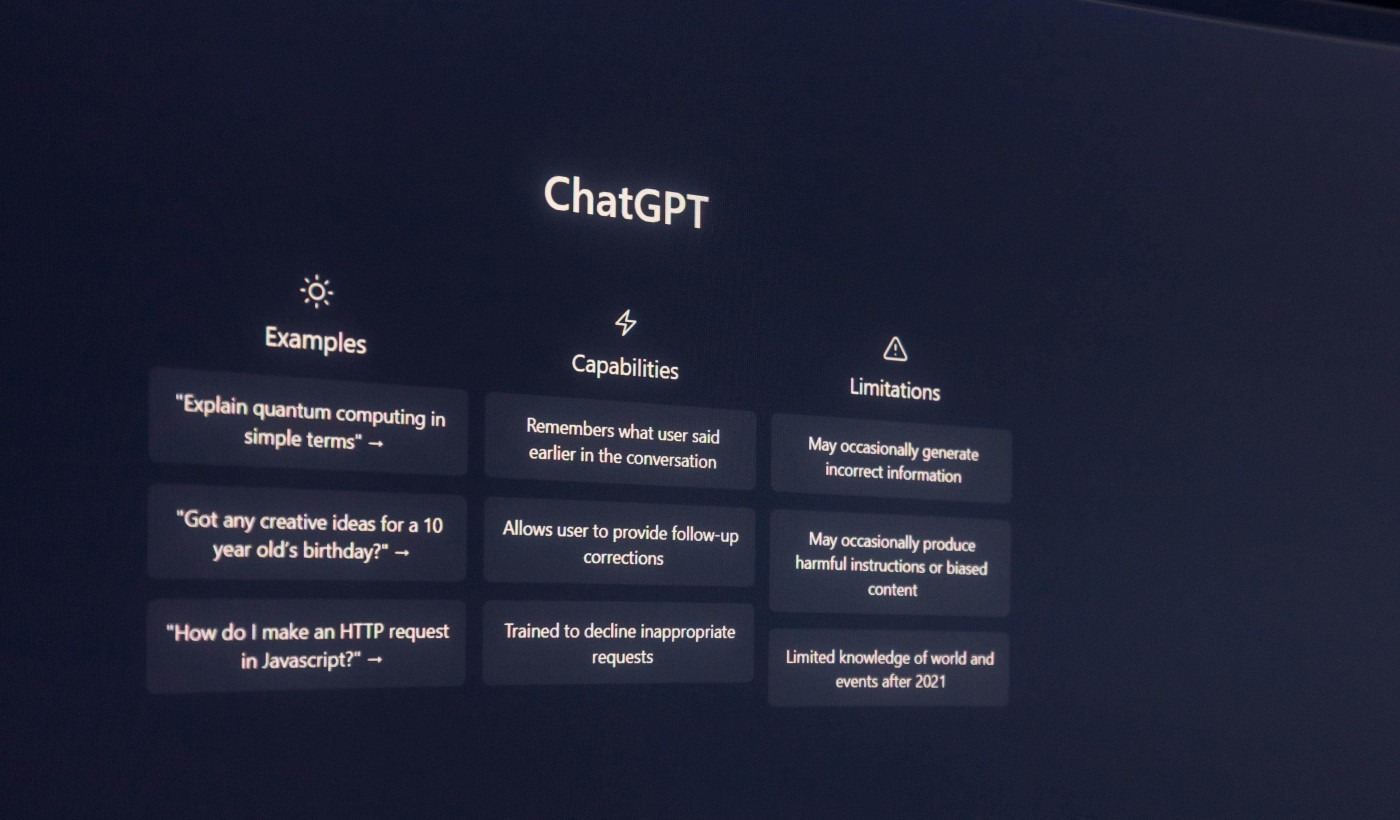

Professor Patel has made it clear: “AI is here to stay. It’s not going to go away, and it’s going to be even more pervasive in everything that we do.” Many scholars have, likewise, acknowledged that ChatGPT and AI technologies are capable of revolutionising academia, but the way in which these generative AI systems are used could surely undermine academic integrity. For some, AI’s disruptive power outweighs the benefits of AI technologies in academia altogether.

The rapid speed at which AI-assisted technologies are being adopted by students has left universities with the sudden need to grapple between balancing the risks to academic integrity posed by AI and embracing the technological advancements these generative systems may offer.

New figures obtained by Times Higher Education have seen universities nationwide witnessing a rise in students illicitly using AI-assisted technologies in assessments, alongside the number of penalties skyrocketing. The University of Sheffield reported 92 cases of suspected AI-related misconduct in 2023-24, with 79 students facing penalties. The year ChatGPT launched, the university saw just six suspected cases and six penalties in 2022-23. Under similar circumstances, the University of Glasgow faced overwhelming rates of suspected AI cheating with cases reaching 130 in 2023-24, compared with 10 suspected cases in the 12 months prior.

The rapid speed at which AI-assisted technologies are being adopted by students has left universities with the sudden need to grapple between balancing the risks to academic integrity posed by AI and embracing the technological advancements these generative systems may offer.

Research from a Warwick International Higher Education Academy (WIHEA) report found students are in fact in favour of AI’s increasing presence in academia. From the student’s perspective, research findings highlighted that the application of AI in education cannot be ignored and must be embraced in education as it is in the workplace and wider society. The findings suggested that “AI provides a new avenue of saving time on some work while spending more time on others,” pointing to the idea that “access to information generated by AI can bridge barriers and enhance understanding, promoting inclusive learning environments.” Other statistical evidence has revealed that 53% of university students claim their grades have improved since using AI. Similarly, university educators have jumped on the AI bandwagon with 85% supporting that artificial intelligence is positively impacting higher education.

One case, however, has shown the risk AI usage poses to the academic future of students. Under the pseudonym Hannah, one student spoke to the BBC about her experience with AI. The student used AI to write one of her essays when she faced back-to-back deadlines while suffering from Covid-19. Hannah’s misuse of AI was discovered by her lecturer during a routine scan of essays with AI-detection software. After scoring a zero on her assignment, Hannah received an email from her tutor outlining the university’s suspicion of academic misconduct. Hannah was then referred to an academic misconduct panel. Despite holding the power to expel students for cheating, the panel ruled that there wasn’t enough evidence against her.

Discrepancies between privileged and underprivileged students accessing these systems have raised concerns for university leaders and social mobility activists across the country.

Hannah told the BBC: “I do massively regret my choice, I was achieving really well, getting a lot of firsts, and I actually think that might have also been the problem, that I need to maintain that level of grades, and it just kind of really pushed me into a place of using artificial intelligence. It felt really bad at the end of it, it really tainted that year for me.”

Another clear issue with the sudden rise in AI technologies over the past year is the potential that universities who begin encouraging AI usage amongst students will “widen the gap” between “those who have the resources and the knowledge to use AI, versus those who do not.” With companies introducing fees for access to more advanced versions of generative AI systems, discrepancies between privileged and underprivileged students accessing these systems have raised concerns for university leaders and social mobility activists across the country.

Polling published by the Higher Education Policy Institute (Hepi) has found the uptake of AI-assisted technologies has been higher among students from more privileged backgrounds, who represent 58% of the total population of users of AI at university. The remaining 51% were from the least privileged backgrounds.

Class discrepancy concerns are only the tip of the iceberg for the ethical problems facing AI-assisted technologies. Evidence from the Information Commissioner’s Office found that “[t]he data used to train and test AI systems, as well as the way they are designed, and used, might lead to AI systems which treat certain groups less favourably without objective justification.” The Office refers to the fact that AI systems learn from data which may be unbalanced and/or reflect discrimination, subsequently producing outputs which have discriminatory effects on people based on “gender, race, age, health, religion, disability, sexual orientation or other characteristics.”

The University of Warwick has published its own framework on the institution’s approach to the use of AI and academic integrity, offering guidance to both staff and students regarding acceptable AI usage. In the framework, the university defined Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools (GAITs) as “a type of intelligence tool trained to generate a human-like response from pre-existing large data sets. GAITs, such as ChatGPT create content which is different to other AI tools such as those included with Word which check and correct spelling and grammar.”

When asked to draw the line between problematic and acceptable use of GAITS, universities state that students cannot use these systems to replace learning, to gain an unfair advantage, to rewrite work or use it for translation, to synthesise information, or to create content passed off as your own. The University of Warwick treats this usage as academic misconduct. Be that as it may, if students choose to use AI as a revision tool, to structure plans, or to refine their work, the university requires clear acknowledgement through a student declaration statement.

The university’s implementation of AI usage guidelines is symbolic of the changing nature of academic integrity and study habits in universities across the country.

Comments