The poetry collection – Mary Oliver: the poet of the natural world

American poet, Mary Oliver, was famous for her writing centred around the quiet and mundane occurrences in life, particularly within the natural world. Born and raised in Cleveland, in the early stages of her pursuit of writing, Oliver would build huts of sticks and grass in her local woods and scribe poems inside them. This intimate exposure to nature inspired her poetic voice, rooted in a profound reflection of nature. During her adulthood, Oliver moved to Princetown, which surrounded rural Cape Cod landscapes, soon becoming a muse for her poetry. As a pure celebration of flora and fauna, her poetry bridges the intersection between the human world and the natural world. Drawing on inspiration from the Romantic period, Oliver encouraged reflection upon nature as a form of renewal through her poetry. In the latter parts of her career, Oliver began to dive into greater personal realms with her writing, eventually winning the Pulitzer Prize for her work entitled American Primitive.

Prior to last summer, I had only read a few of Oliver’s poems that I came across online and was not at all familiar with her artistry. During the summer, I had the fortune of stumbling across her collection Blue Horses in a bookshop and was excited to uncover more of her writing. Her poetry was a great comfort to me. Despite her simplistic use of language and her seemingly ordinary subject matters, Oliver still manages to touch upon meaningful concepts such as redemption and forgiveness. There is a tone of softness echoing throughout her poetry. Unlike the Romantics, Oliver does not overly glorify nature as a separate entity from humankind. Instead, she portrays the human as a token of the natural world too, offering the notion that like the animal or the plant, the human is worthy of absolution too.

Outside of Blue Horses, one of her most famous poems ‘Wild Geese’ somewhat illustrates these concepts of human redemption through our connection to nature.

‘You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting. You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.’

(Taken from ‘Wild Geese,’ 1986)

In the opening of the poem, Oliver contradicts the lesson we have all been imbued with from a young age, that we must be ‘good’. However, she is no way promoting immorality, rather she is painting an idea of morality being subjective. To Oliver, prescribed ‘good’ and proper actions like ‘repenting’ are not the only way in which goodness can be accomplished.

Oliver is challenging the human flaw of being too objective and instructional concerning the idea of morality – perhaps a critique of religion

Oliver is challenging the human flaw of being too objective and instructional concerning the idea of morality – perhaps a critique of religion. Simultaneously, she provides comfort to her readers by imploring them to draw upon the ‘soft animal’ within them, whatever that may be. Through this, Oliver has evoked notions of self-forgiveness and an overarching forgiveness of humanity, through the ambiguous figure of the ‘soft animal’ telling us that we must find what we ‘love’ and draw passion from that rather than dwelling on our past misfortunes. I find the opening of ‘Wild Geese’ to be a compelling one, something that captures a sense of relatability to all who read it.

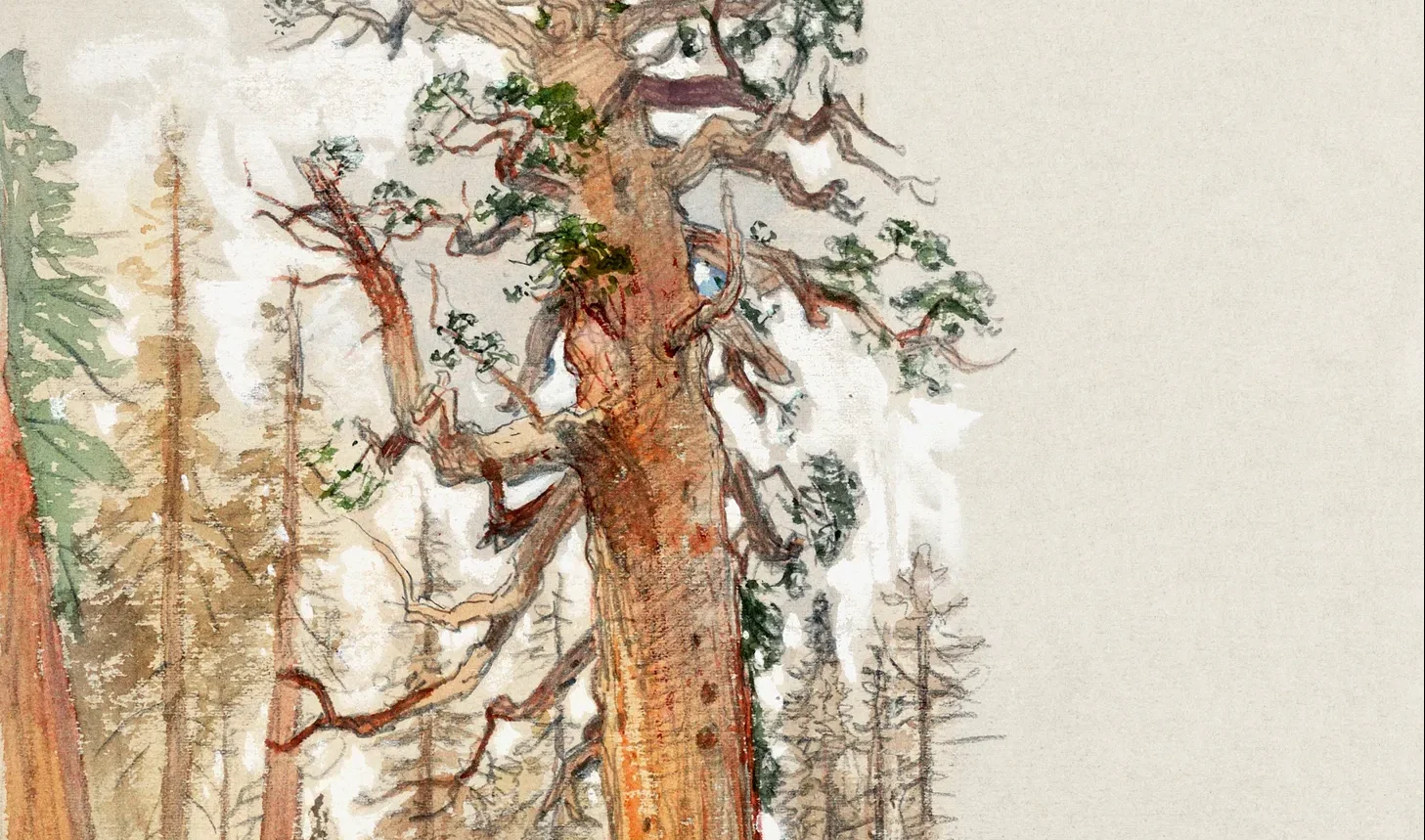

In her poetry collection, Blue Horses, Oliver “reminds us of the transformative power of attention and how much can be contained within the smallest moments”, as detailed in the blurb. I feel as if these notions of the mundane are best captured in her poem ‘The Country of the Trees’. Within the poem, she describes a utopian ‘country’ of trees, as the title suggests, where hierarchy does not exist, where those who inhabit the country are looked after and where contentment is rife. Although this may sound peculiar, I really admire Oliver’s crafting of this country through her natural imagery. In the third stanza of the poem, she states “when it is cold they will be given blankets of leaves … when it is hot they will be given shade”. Through the anthropomorphised figures of the trees, Oliver is able to comment on the roots (both plant and otherwise) of human nature in that we are all fundamentally being looked after and looking after something, whether it be a friend, a higher power, or in this case a simple spot of shade.

‘Neither do they ever have any questions to the gods— which one is the real one, and what is the plan.

As though they have been told everything already,

and are content.’

(Taken from ‘The Country of the Trees,’ 2014)

In the final stanza, Oliver finalises her ideas of contentment weaved throughout the poem. In doing so, she illustrates how in this ideal world, there is an element of blissful ignorance that results in feelings of satisfaction due to this unknowingness. Here, the poet is perhaps pleading with humankind to not become too consumed by its own urge to uncover every figment of knowledge, but rather to let some things go and become relieved in doing so.

I’d recommend Oliver for anyone interested in beginning to read poetry. Her poems are easy to understand but uncover earnest convictions that encompass sentiments of nature, the beauty of the monotonous, religion, spirituality, and unconditional love. Other recent works by her include: Upstream, a collection of essays reflecting on her life and journey as an artist, as well as, Devotions, a collection of selected poems unravelling more themes of nature and the human spirit.

Comments (1)

Did you mean Provincetown? Typo alert!