Weaving History successfully portrays a forgotten thread of working class history with an exploration of the Lancashire Cotton Famine.

“Maybe we should bring poetry sections back in newspapers”, Weaving History’s writer and presenter, Ruth-Anne Walbank, expressed when sat alongside producer Daniel Woodburn to discuss with The Boar their podcast and the significance of their exploration of working-class poetry from the Lancashire Cotton Famine. This comment followed the acknowledgement that social media (as a form of modern oral history) has become what poetry in local newspapers once was to working-class individuals in the industrial North.

Weaving History successfully provides a thorough interpretation of an often forgotten, tumultuous time in working-class history

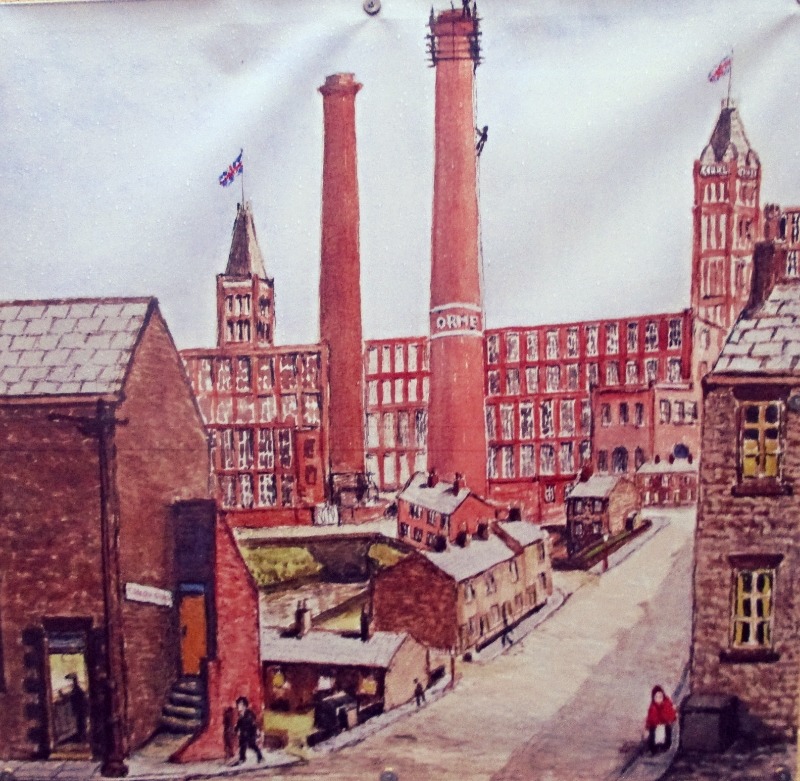

Weaving History is a six-episode mini-series exploring the nineteenth century Lancashire Cotton Famine through the perspective of working-class history, by examining a menagerie of poetry, newspapers, and other pieces of notable Victorian Literature. With conversations with leading experts in the historical field and interspersed poetry readings, Weaving History successfully provides a thorough interpretation of an often forgotten, tumultuous time in working-class history.

This history is often hard to locate and rarely preserved as the individuals concerned were depicted as “nobodies”

Bringing this element of working-class history to life is at the forefront of Weaving History. However, this is no surprise given both Walbank and Woodburn are from working-class roots and recognise the lack of accessibility present in studying working-class histories. Walbank’s study of this history follows a respect of the working-class tradition in poetry being orally recited, a cultural factor which had been taught by their grandparents. Despite their familial history and the countless hours they spent in archives locating this history, Walbank recognises its erasure is due to accessibility issues and restrictive curriculums, stating that, “even if you are from Lancashire, there is still a good chance […] you’re never going to come across it.” Furthering this, they claim it is “silly” that individuals only have access to these histories during higher education, as access to these sources would provide a “more applicable or emphasizable” interpretation of the nineteenth century to modern audiences over some literary classics. Additionally, Woodburn’s experience in the heritage sector secures this thesis, highlighting that this history is often hard to locate and rarely preserved as the individuals concerned were depicted as “nobodies”, corresponding to its historical material being deemed as unimportant. Weaving History runs with this reoccurring thread to rectify education’s failures while bringing working-class words and histories to the forefront of listeners’ minds.

Woodburn’s experience in radio and podcast production shines through

Weaving History’s listeners have been meticulously considered, from the content of the podcast down to its structure and curation. From speaking to both Walbank and Woodburn, they had eight interviews between one to two hours long to edit into two hours’ worth of audio time for Weaving History. While being inundated with content is a positive for Woodburn, Weaving History is highly commendable at keeping listeners engaged. Woodburn’s experience in radio and podcast production shines through, especially involving their motives for producing Weaving History as a short-format podcast. Woodburn recognises that a lot of podcasts fail where they have not been carefully curated to keep listeners engaged. They insist that the interspersed fragments of poetry (which were edited in during the final product) “loop the listener back in”, due to the change in tone and subject.

You can’t talk about this [the Lancashire Cotton Famine] without talking about black history, without talking about slavery, emancipation and abolition, and all the rest that comes with it

– Ruth-Anne Walbank

Additionally, Walbank desired Weaving History to have a curated approach to consequently make it “a bit more bite-sized [and] a bit more accessible”, as much of their research during their PhD thus far has encompassed making history and literary material readily available to all. For instance, the episode ‘Blood on the Bales’ features an intentional inclusion of historical context surrounding the American Civil War and slavery during a powerful conversation with Dr Onyeka Nubia, in order to decipher the impact of these events on working-class poetry. When asked whether discussions of these themes were intentionally integrated into the podcast, Walbank disclosed, “you can’t talk about this [the Lancashire Cotton Famine] without talking about black history, without talking about slavery, emancipation and abolition, and all the rest that comes with it. You can’t not talk about it, it’s so innate.” So much so, that they acknowledge the necessity to decolonise the curriculum so that Black History is effectively taught, to subsequently comprehend intersectionality and how both black and working-class histories are more interwoven than we might think.

A common thread throughout Weaving History involves dispelling historical stereotypes of the working class being uneducated, rowdy, and associated with the criminal class, by exhibiting their poetry as a source of intelligence alongside a platform of patriotism and communal solidarity. This ideal is pertinent in the episode ‘No Work, At Home’ during an exploration of Richard Ryley’s diary (a cotton weaver who lived during a portion of the cotton famine) and his documentation of his personal history, which incorporated his experience of unskilled manual labour. Breaking these stereotypes is evidently paramount throughout Weaving History, as working-class poetry provided individuals with a conscious voice to protest for enfranchisement and global change.

Poetry is timeless because it can be reinterpreted. If you can find value and you can find meaning from something written 100 to 200 years ago, then that’s what keeps it alive in the public consciousness

– Daniel Woodburn

The poetry displayed within Weaving History exhibits an applicability which listeners are able to relate to their contemporary circumstances. Woodburn highlights, “Poetry is timeless because it can be reinterpreted. If you can find value and you can find meaning from something written 100 to 200 years ago, then that’s what keeps it alive in the public consciousness.” With that being said, the preservation of written material from the Lancashire Cotton Famine and the attention given to its history from Weaving History alerts to the cyclical nature of history, in terms of its relevance to current events – but of course, with poetry in newspapers being replaced by posts on social media uploaded during times of local, national, and global crises. Walbank compared such events to contemporary concerns with climate change, along with the Ukraine War which consequently saw Britain and other nations experience supply chain issues involving crops, oil, and gas. Woodburn compares the Lancashire Cotton Famine to periods of high unemployment and recession during history, more specifically the 2008 financial crisis.

Weaving History compellingly notifies its listeners of a widely forgotten period of working-class history. Whether you are an academic, historian, or a casual listener, Weaving History provides ample opportunities to introduce individuals to a new perspective of literature whilst learning and comprehending an otherwise untold history.

Comments