Why Martin Scorsese is right about superhero movies

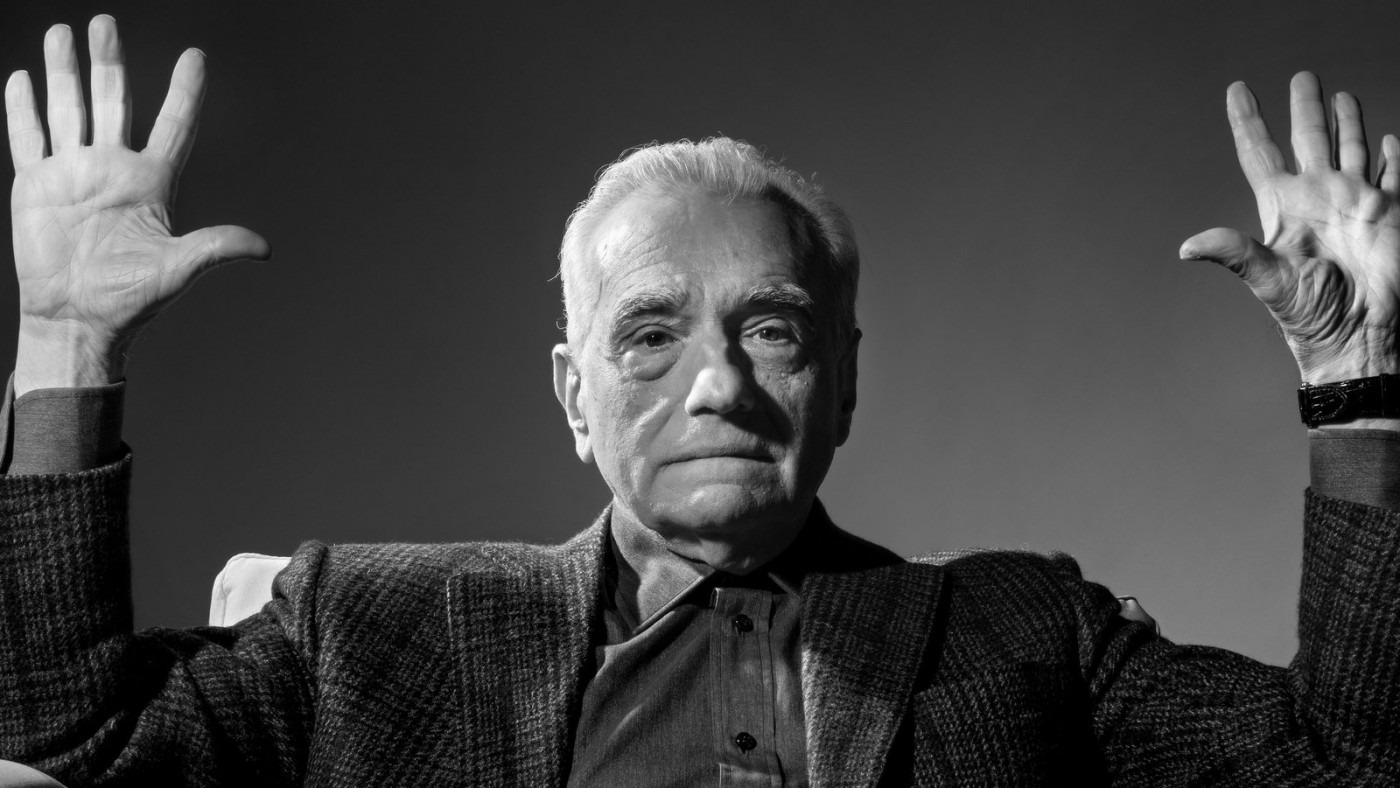

Once again, Martin Scorsese has stirred up the contentious debate surrounding the Marvel Cinematic Universe and superhero films in general, probing its effect on the public image of cinema and its status as an art form. In an interview with GQ promoting his latest venture, Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese reiterated his perspective on the damaging impact that comic book movies were having on audiences’ perceptions of cinema, arguing that coming generations would view these franchises as the predominant thing that the industry has to offer them. His view is that these movies are “manufactured content”, insofar as their goal is to provide amusement, as opposed to enrichment. In essence, Scorsese maps out a bleak future, one that he passionately urges a pushback against, in which comic book movies command the big screens, leaving little room for individual creators to showcase their crafts to wider audiences. Or perhaps, more frighteningly, this is the future we are already living in. Amongst his comments, the 80-year-old director acknowledged his own mortality (“How much longer can it be me?”), a stark reminder that the beloved filmmakers of his era will not always be around to keep up the fight for cinema.

Scorsese is not the only director to have voiced these concerns. Francis Ford Coppola, for example, has gone on record to describe comic book movies as “despicable”, arguing that they fail to use storytelling as a medium to inspire audiences.

Predictably, the legendary filmmaker’s latest intervention has met with several reactions, opening up questions regarding the future of cinema. Does Scorsese simply represent the ageing class of directors reluctant to embrace the modern cinematic era of action-packed franchises and superheroes galore, or are his words a prophetic warning about the dangers of indulging in Marvel mania while the fate of authentic cinema hangs in the balance?

The crux of Scorsese’s argument rests on his belief that comic book movies fail to exhibit a personal level of artistic expression, a story to be told through the creator’s individual voice

The crux of Scorsese’s argument rests on his belief that comic book movies fail to exhibit a personal level of artistic expression, a story to be told through the creator’s individual voice. In his words, “You’ve got to say something with a movie”, otherwise it is just content produced simply to provide instant gratification for the viewer. They do a disservice not only to cinema but also to audiences; the prolific manner in which studios endlessly churn out films of this genre inevitably leads or perhaps, according to Scorsese, has already led to their acceptance as the embodiment of modern cinema. In contrast, the films expressing intimacy and originality are designated to the ‘indie’ group, marginalised to a smaller audience while funds move in favour of the blockbusting money-making franchises.

Some would protest, citing the popular appeal of such movies in bringing hordes of engaged fans to cinemas. After all, if these films are consistently successful in packing theatres and satisfying moviegoers, why is this such a bad thing? To answer this question, one has to first determine what the purpose of cinema is. For Scorsese, the purpose of cinema is to leave audiences enriched and enlightened, not just momentarily but with a lasting impact that allows them to gain something from their viewing experience. For this to occur, directors must have artistic control over their projects, rather than remain constrained at the behest of studios. Scorsese reflects this attitude in his own work, from Mean Streets to Silence, his films consistently embody a sense of his personal identity, whether that be his Italian heritage or his Catholic faith.

In this light, Marvel movies are seen to prioritise profit over artistic endeavour. This is not to suggest that such movies do not provide an enjoyable viewing experience or demonstrate commendable effort from crew and cast. However, when these comic book movies are being released at such a rapid rate, taking up so much exposure and financial support, where does this leave those filmmakers who venture on riskier grounds, with original stories to put to the screen and an abundance of talent to showcase? Those who find themselves aggrieved by Scorsese’s comments should consider his remarks not as an attack on Marvel but as a defence of the art of cinema that he and filmmakers like him are fighting to protect.

The cinema of human experiences, conveyed through an audacious narrative structure and expressed through the director’s unique vision. A film that is designed to provoke audiences, to inform them of a pivotal moment in world history, and to leave them reflecting on their mortality as they watch the credits roll.

Although the future of cinema may seem to be in peril at the moment, it has certainly not reached the point of no return. Just as comic book franchises are a thing of the present, auteur cinema is still alive, with creatives using new technology to experiment with storytelling through cinema. Scorsese has drawn attention to the accomplishments of contemporary filmmakers, including Christopher Nolan and the Safdie brothers in particular, as those who exemplify this artistic form of cinema. Nolan’s most recent picture, Oppenheimer, an acclaimed biopic of the American physicist grappling with his moral conscience after mastering the bomb, epitomises Scorsese’s definition of cinema. The cinema of human experiences, conveyed through an audacious narrative structure and expressed through the director’s unique vision. A film that is designed to provoke audiences, to inform them of a pivotal moment in world history, and to leave them reflecting on their mortality as they watch the credits roll.

Combined with Greta Gerwig’s feminist sensation Barbie, a compelling story of womanhood told through the lens of a female director, the Barbenheimer phenomenon is proof that audiences are still geared towards individual-minded projects bearing the personal stamps of their respective filmmakers. All is not lost yet.

If the preservation of art is truly a worthy cause, then Scorsese’s plea to fight back and never give up must be heeded. The time has come to save cinema from the superheroes.

Comments