My life with Milan Kundera

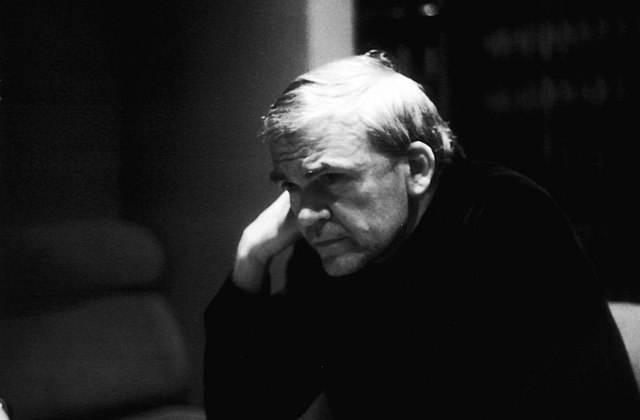

There has not been a writer that stayed with me ever since my teenage years. I must have been around the age of sixteen when my father, an avid fan of literature, recommended me a short story collection called Laughable Loves by a Czech author named Milan Kundera. I remember opening the destroyed copy that has occupied my family’s nightstands for many years; I found it intelligent, funny and also very playful. But now, after 94 years of living and many years of writing, Milan Kundera died on 11 July, 2023.

A series of stories, ranging in lengths and styles map love in all its forms. In one of the stories, titled The Hitchhiking Game, a couple going on holiday decides to act like strangers to each other; lovers are, because of this, turned into enemies and see each other with disgust. In Eduard and God, a boy starts dating a Christian, which is not deemed appropriate in communist Czechoslovakia, and thus he has to decide what to do. The book was published in 1970.

Kundera has been a prolific writer and even though he has been mainly recognised for his novels — for an international reader, Kundera’s name is deeply connected to his 1984 novel: The Unbearable Lightness of Being. He was also a poet, an author of plays, and, for some scholars, an essayist. However, his novels contained features of philosophical essays — from his long discussions of folk music in his first novel The Joke — a text that a Slovenian philosopher and cultural critic Slavoj Zizek called Kundera’s best — to an explanation of why girls always walk in pairs. The connection between philosophical thought and fiction has obtained him many fans.

My classmate and friend, Kishan Katira, currently finishing his master’s degree in Critical and Cultural Theory at the University of Warwick, is one of them. He has only read The Unbearable Lightness, but he had recommended it to four other people to read. He wrote to me in a message that he sees a connection between this novel and Notes From Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky, as they “both present people as unhappy with the fact that they depend on other people”. Kundera’s writing has been influenced by many, for example authors like Franz Kafka, Giovanni Bocaccio, and many classical music composers.

Kundera is also interesting for the Czech reader due to another reason: his ban on artistic adaptation

However, speaking of Kundera solely as a Czech author would do him injustice. This text does not aim to explain the not-so-great relationship some Czech readers have with the author, as I do not view it as correct so close to his death. Also, me being a follower of Roland Barthes’ 1967 essay The Death of the Author, I do not see anything useful or valuable in diving into controversies connected to the author’s private life. Kundera’s name became heavily discussed in 2020 after Czech writer Jan Novák published an almost 900-page-long literary biography of him. There, he framed Kundera as someone whose actions lead to imprisonment of others. A Czech literary scholar and critic Petr A. Bílek stated, in a review of the book, that Novák is “in the sphere of general and literary history an egocentric dilettante” due to his tabloid-like way of framing the author. Maybe in the future I will have more to say about the Czech author who was as loved as he was hated in his hometown. That, however, seems like a battle to be fought some other time and somewhere else.

Kundera is also interesting for the Czech reader due to another reason: his ban on artistic adaptation. The Unbearable Lightness of Being begins with a note: “any film, drama or television adaptations are banned”. This, existing on the very first page of the 2006 version of the book is in a sense comedic, considering the 1988 film directed by Philip Kaufmann, starring Juliette Binoche and Daniel Day-Lewis as Tereza and Tomas. A reader must forgive me: an essay exists, or at least a translator’s note, somewhere, where Kundera’s hatred towards adaptation is mentioned and explained. I, unfortunately, am unable to find it at the moment.

Reading Kundera is like going on a first date with a beautiful girl to a fancy restaurant

I was continually reading Kundera’s work ever since my high school years. There was, however, a hiatus for a Czech reader; some pieces got translated to Czech only a couple of years ago: La fete de l’insignificance (2020) and L’Ignorance (2021). Kundera left Czechoslovakia in 1975, seven years after the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, and started living in Paris. His hometown was not his hometown anymore — and that is one of the reason why I rate L’Ignorance so highly.

Since I started living in England in 2018, the book spoke to me in a way a book has not done in a long time. It is about Irene, an emigrant, who left communist Czechoslovakia and moved to France. Coming back after 20 years, she not only meets her old love who she had not seen for many years, but also meets her old friends, whose lives changed just as hers.

There is so much to say about Milan Kundera. His writing has influenced me and truly changed my life. I have always viewed him as one of the two biggest writers of my country, the other being Bohumil Hrabal. I came up with an analogy about the two: while reading Hrabal is like going to a pub to drink cheap pints with your friends, reading Kundera is like going on a first date with a beautiful girl to a fancy restaurant. Both have something that the other does not — and both are enjoyable in their own way. In the terms of literature, however, I have always enjoyed the latter a bit more.

Comments (1)

I am a big fan of Kundera too and I was really pleased to read this tribute 🙂

His work is philosophical and poetic, and psychological and comic! I am in love with this. It was the first time that a man made me question my relation to love, memory, and death while making me laugh. My life objective is to read everything he has ever written.

My favourite chapter of all time is a chapter in the Unbearable Lightness of Being, where Kundera writes a ‘dictionary’, as he calls it, and explains why words -such as ‘woman’, ‘cemetery’- have different meanings for two different persons. That was brilliant, his ability to dissect and analyse souls.

Kundera has genuinely changed my life.