The rise of Greek retellings

There are certain names that are making themselves big through the medium of Greek retellings. The tragedies they explore were, in another time, the only form of performative entertainment. But nowadays, when the modern consumer is spoilt for choice, the popularity of these stories remains, and their relevance is continuously re-established. From Homer to Shakespeare to contemporary novelists, the impact of Greek mythology lives on through the passion of the authors who write about them.

The themes that stand out the most within Greek mythology – love, lust and war – are those that are most compelling.

Other brands of retelling have experienced moderate success. For example, a wealth of fairy tale retellings has established prominence in not only literature but also film, TV and theatre. But, in terms of mythology, stories based upon Greek myth have certainly climbed to the top of the ladder. Emma Herdman told The Guardian that “There will always be an appetite for a retelling that offers us a new way into thinking about how we live today, for a retelling that’s beautifully written and has emotional perspicuity”. But what is it that induces a writer to embark upon retelling a story? The key reason that so many readers will pick up Greek retellings as soon as they hit the shelves is the content they portray. The themes that stand out the most within Greek mythology – love, lust and war – are those that are most compelling.

In the past, I have found a repetitive nature to reading novels like A Thousand Ships, The Song of Achilles and The Silence of the Girls consecutively. At first, I will thirst for more of the mythological world and the themes that exist within it. Most of these novels will vary in their narrative and stylistic choices, having been written by an array of authors. But being told the same story over and over again, with sometimes minimal changes but often the same characters and relationships, is exhaustive and bleeds all possibility from the reader’s imagination.

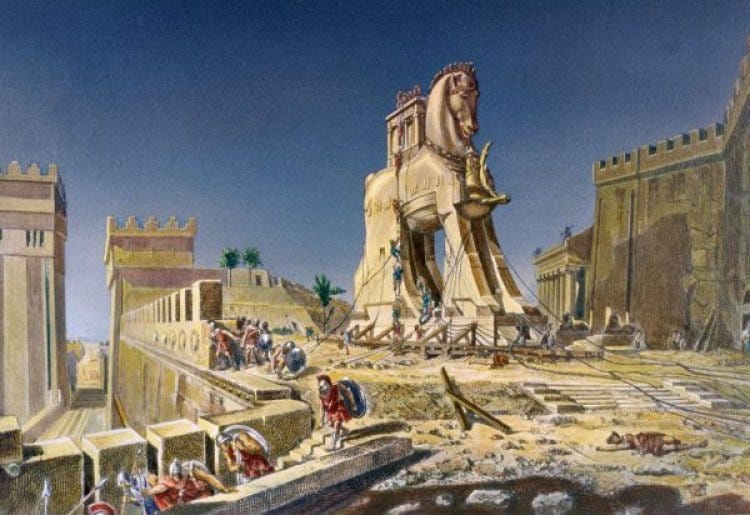

Surely once you’ve read one, you’ve read them all. How many different angles can be taken in regard to the Battle of Troy? Clearly, these retellings need to bring in fresh angles. Which is why, currently, the spin that authors seem to be taking is often that of a feminist twist.

Pat Barker’s The Women of Troy and The Silence of the Girls both tell the feminine perspective of tragedies that previously predominantly focused on the men involved instead. But, in such a story, where the ending is already pre-destined, there is never really true power commanded by the women; their stories cannot be re-claimed when the key moments are already told.

A connection has formed between the Greek retelling and the feminist interest.

The novella The Penelopiad, featuring the story of Odysseus and Penelope, was praised following its release in 2005 as a “feminist perspective” by Washington Post due to its portrayal of story-building female characters and women-centric themes. Yet, author Margaret Atwood proposes that there is nothing particularly feminist about her retelling. It is only that “every time you write something from the point of view of a woman, people say that it’s feminist.” But the demographic of the writers and readers of these stories currently stands out. A connection has formed between the Greek retelling and the feminist interest. Even when awarded for their work, these authors gain a significantly greater dominance in the longlists for the Women’s Prize for Fiction than the non-gendered Booker Prize.

Stephen Fry, following the publishing of his novel Mythos, told The Telegraph that Greek mythology is “addictive, entertaining, approachable and astonishingly human.” Mythos, and its sequel Heroes, sets out to make the usual stories approachable for those without “classical education”. This is, arguably, an issue that a lot of other retellings are criticised for not taking into account. But, does the author have an obligation to contextualise their text for the widest possible audience? It seems that the popularity of existing Greek retellings illustrates that success is still available to those who write for a niche crowd.

Another issue established by the regularity at which the exploration of Greek mythology is currently published is that there is no transparent line between what is a work of fanfiction, and what can be considered a true “retelling”. Other cultures’ mythologies, whilst occurrent in modern literature, simply are as frequent and thus are not what we think of when we think of “retellings”.

Some authors, like Daisy Johnson’s Everything Under, which reimagines Oedipus Rex, take the underlining element of Greek mythology, placing it in a different setting, often one more familiar to the writer and a modern audience. Johnson’s novel was praised by The New York Times with the achievement of “making something very old uncannily new”, in what seems to be an attraction towards literature that puts a modern spin on age-old themes.

The discussion always leads to how the retellings are not true to the classics’ source.

There is no true obligation to stay close to the source material, other than in breeding interest from readers who are familiar with the original myths that are being twisted. Some readers complain that inaccuracies in retellings are blasphemy. Often in conversation about such novels, the discussion always leads to how the retellings are not true to the classics’ source. But then it is possible that the stories are already so different from how they were first told, and that there is no further harm by adding further manipulators to the plots and characters.

The rise on #BookTok of Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles particularly stands out. Novels about homosexual men serving as warriors in an army are very rarely the subject of Women’s Prize for Fiction winners. Yet, this book’s passionate and emotive exploration of love and death is so beautifully written, that it stands out entirely on its own.

Frequently over the last decade or so, the novels above have been honoured with making the shortlists of many literary prizes. The most recent success in the popularity of Greek retellings is that of the novel Stone Blind being longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction. Natalie Haynes’ novels are not her only creative passion towards Greek mythology. In addition, she narrates a podcast Stand Up for the Classics which demonstrates that although the source material may be embellished in literature form, it is still relevant to discuss the origins of these stories and how they have developed the characters we know today.

Comments