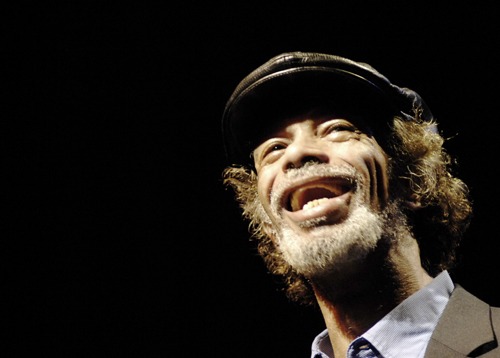

The death of the protest song

On his song ‘The Revolution will not be Televised’, Gil Scott-Heron details how revolutionary activism will not exist within corporate entities, concluding the song with the idea that “the revolution will be live”. It was one of the defining protest songs of the twentieth century, but also, even if inadvertently, details the death of the protest song within modern music. Over the past few decades, songs explicitly discussing protest and pushing the listener to engage in these acts are dwindling and are almost non-existent. In the current musical landscape, they no longer exist where they thrived across genres a few decades ago.

Countless songs were banned

Of course, to say that the protest song is dead is not to say that there are no songs that discuss politics at all. Kendrick Lamar has spent his career detailing the experience of being a black man in a racist America, Rina Sawayama’s ‘XS’ explicitly discusses the shallowness of consumerist culture, ‘Your Teeth in my Neck’ by Kali Ulchis is about being exploited by the rich in order to make them money, and YUNGBLUD has built an entire career off of songs that seek to appeal to disenfranchised youth. However, these aren’t protest songs – they’re too introspective, too analytical. Even the ones that present themselves as a cry for revolution are so wound up in the aesthetic of appearing as a progressive or a revolutionary that the actual strives for political progress are rendered void.

So, what changed? Throughout the twentieth century, there were legions of artists who would write songs that call for protest ranging from Bob Dylan to Rage Against the Machine to a lot of the artists working in the punk scene. However, at the start of the 21st century, there was a shift in this mindset, something that likely originated from the Bush administration in the fallout from 9/11. Following the tragedy, American culture and the western world more generally fell into line with the conservative ideals of the Bush administration. There was an idea that anyone who was not fully endorsing a sense of western supremacy was a threat to the entire institution. Whilst this came from a genuine place of hurt that was vaguely covered by the idea of removing anything that could be vaguely deemed an opposition, it quickly spread beyond that. Following the attacks, countless songs were banned from the overtly political, like Black Sabbath’s ‘War Pigs’, to the poorly worded, like Alanis Morrisette’s ‘Ironic’. To those who could hold sway over culture then, there was an immediate push for these dissenting voices to be silenced including in music.

However, it was not just the oppression of culture that led to the death of the protest song but also the rise of social media. Since it was first established, different social media sites have become clear places for people to start focusing on aesthetics over actual substance. Being able to conform to a pre-set aesthetic of the culture that existed in the society was imperative. This aesthetic process is something that was quickly extended to the art that people consumed. To listen to the right songs and disavowing the wrong ones would allow you to be truly a part of the in-group on an aesthetic level.

Politics and music are always two concepts that are heavily intertwined

These two converging ideals were the perfect combination to kill the protest song and they were able to work together perfectly regarding The Chicks. In 2003 the band, formerly known as The Dixie Chicks, were doing a concert in London and the lead singer, Natalie Maines, stated that she was ashamed that the president of the United States was from Texas. This relatively tame statement soon spiralled out into mass hatred for the band. Online forums and message boards found out about this small statement and campaigned for the band to be removed from the radio and record stores. These communities had become so connected to the idea of American supremacy that they had decided to take their ire out on a random country band. What Maines had said, which was a simple throwaway remark, was not relevant but simply the fact that the band had made an aesthetic divergence from what they were previously aligned with. With destruction of The Chicks over such a minor remark, almost guaranteed that the protest song that was once so prominent and beloved would never be able to truly relist in the landscape it was once in before.

Whilst there has always been some retaliation to a protest song it has only grown more prominent throughout the 21st century. The knowledge that any direct call for action will be met by such severe backlash from so many groups and the possible destruction of the career of the artist has made so many people turn away from it as a medium. Politics and music are always two concepts that are heavily intertwined but in the wake of these cultural changes, it is something that is no longer able to prosper and inspire change in the way that it once did.

Comments