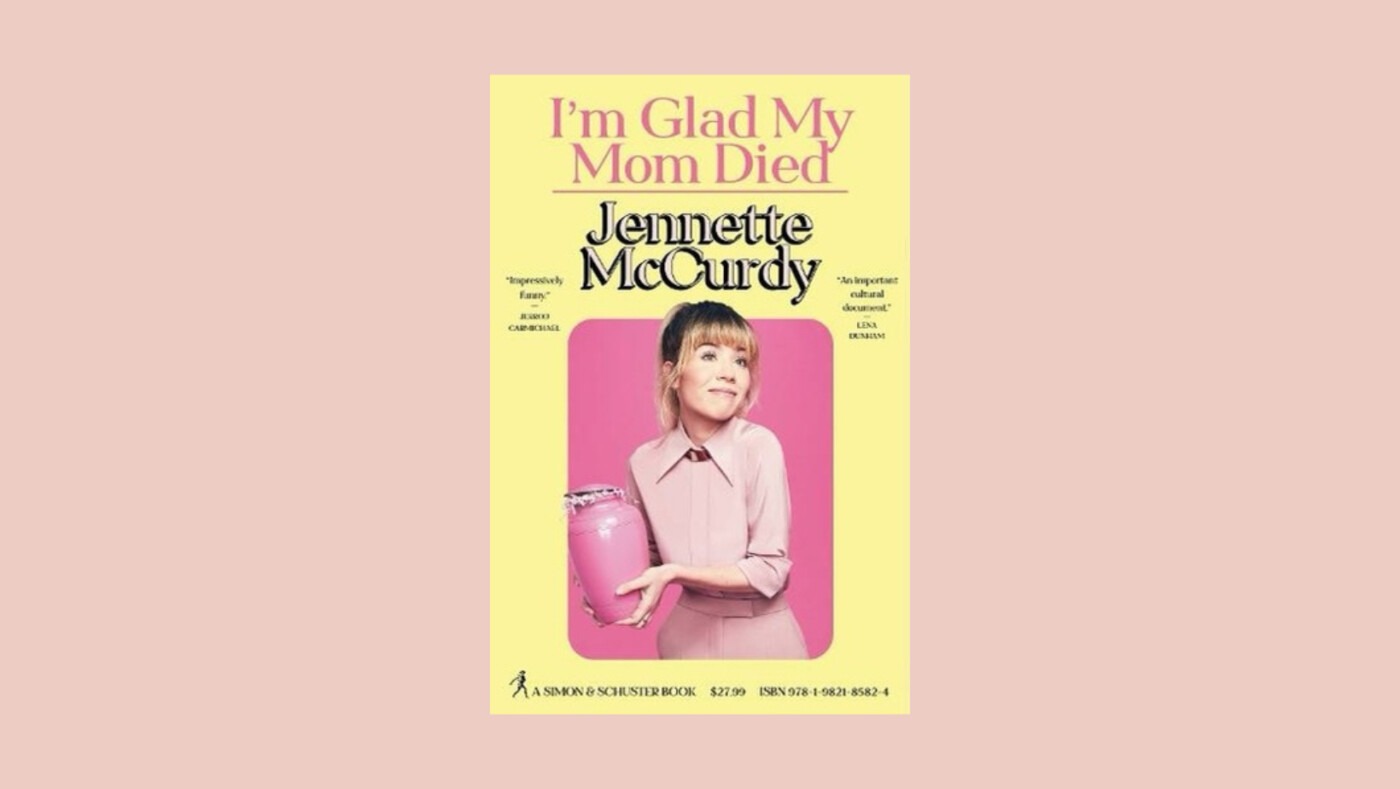

‘I’m Glad My Mom Died’ is THE child actress memoir

Abuse is something that overshadows your entire life, whether you realise its impact or not: that’s the central theme of child actress Jennette McCurdy’s revelatory memoir, (who was subjected to mental, emotional, and sexual abuse for as long as she can remember), which sold out on Amazon the day after release. Even prior to the book being published, I’m Glad My Mom Died, which documents McCurdy’s reluctant transition from childhood to Hollywood, had been a trending topic on social media, for the rawness and honesty seen in extracts. Although the easy-to-read memoir has been acclaimed for revealing the terrible working conditions behind the scenes at Nickelodeon, (McCurdy starred on iCarly and Sam and Cat), it is the heartfelt, confessional descriptions of the actress’s experiences of abuse and mental illness that the book should be recognised for. McCurdy captures the well-known but often unspoken truths of how growing up with an abusive parent can affect the rest of your adult life.

Without reading the book, the title can come across as harsh or even sacrilegious, (McCurdy highlights that they’re the most romanticised of any dead: “moms are saints… we non-moms must heap nothing but praise upon moms”). In how she structures the narrative, McCurdy gradually reveals how unforgivable her mother was like she’s peeling the layers of an onion, one at a time. It’s easy to explain away some of her behaviour: who’s mother hasn’t pushed them into doing things they don’t want to, for the sake of their own good? Who’s mother hasn’t worried about them growing up too fast and tried to restrict their independence a little?

It’s clever how McCurdy lures the reader into the mindset of somebody who’s experienced abuse, clinging to the positive aspects of the relationship and trying to explain away the negative. This is what it’s like to be entrenched in an abusive relationship, particularly with a parental figure, as her mom was kept on a “pedestal” that was “detrimental… to my life and well-being” despite the way McCurdy was treated by her. She captured my experiences well: even though I can recognise that my father was abusive, even typing it out now makes me feel guilty as if I’m betraying him somehow. I want to explain on his behalf. The reader harbours the same mixed feelings towards McCurdy’s mother— sometimes understanding, (she is a cancer survivor and obviously struggles with her own mental illnesses), other times hating her. By the end of the memoir, however, there’s no doubt that the reader has reached the same conclusion as McCurdy herself does: her narcissistic mother stole her childhood and consequently damaged the rest of her adult life.

She notes her discomfort at being forced to try on bikinis for The Creator’s benefit, when McCurdy would prefer to wear a one-piece (at least) or board shorts.

It’s notable that her mother never lays a hand on McCurdy, (she does throw things at her husband), so it’s unsurprising that her behaviour was never reported to anyone. A narcissistic mother doesn’t fit the ‘conventional’ idea of what an abuser is, despite constantly bullying her children, attempting to reduce them to an infantile state, (she worries how McCurdy will shower herself aged 18, as her mother has always done it for her), and creating an unsafe living environment. McCurdy also succeeds in shedding a light on abusive mothers, who are too often overlooked, and her growing up seemed to reminisce with many readers, who shared their own experiences of narcissistic mothers on social media.

From the early chapters, as a budding child actor, it is made clear by McCurdy that this is through no desire of hers. Young McCurdy is shy and anxious, desperate to please. She develops compulsive rituals that she has to perform to alleviate her anxieties and is forced to abandon her dream of being a writer, (although writing gives her a sense of control in her chaotic life) after her mother shows no interest in her first ever screenplay. This is mirrored, later in life, when Nickelodeon revokes her chance to direct an episode of Sam and Cat, despite it being the only reason that McCurdy agreed to star in the spinoff to begin with. Although McCurdy bravely suggests, as a young child, that she doesn’t want to act anymore, her mother turns violent and venomous, only softening when her daughter obediently changes her mind. By the time McCurdy does manage to quit Hollywood, the damage has been done by Nickelodeon: she has been mistreated, abused, and treated as ‘second rate’ compared to her co-star, Ariana Grande. The cherry on the top being that Nickelodeon offered her thousands of dollars to keep quiet about her negative experiences with ‘The Creator’, which McCurdy rejected outright.

Throughout her time in the acting industry, McCurdy was frequently groomed by older men who worked with her, as well as being forcibly sexualised by people involved in production: she notes her discomfort at being forced to try on bikinis for The Creator’s benefit, when McCurdy would prefer to wear a one-piece (at least) or board shorts. While readers might be distraught that McCurdy was further exploited, after already being abused at the hands of her mother, it isn’t just an unlucky coincidence. Studies have found that early exposure to abuse means individuals are at higher risk of ending up in abusive relationships later in life. It’s obvious that McCurdy was vulnerable, both due to her career (we can all think of a handful of child stars that have spoken out about being exploited) and her mother being her only source of knowledge. When McCurdy says she isn’t ready for sex, a much older boyfriend threatens to leave her until she performs a sexual favour, even though she doesn’t fully understand what she’s doing. There’s a string of unstable, unhealthy, and codependent relationships, which mirrors that between McCurdy and her mother.

McCurdy is only able to succeed in recovery by rejecting not just her own disease, but her mother’s, as well as the expectations that her mother had surrounding food, weight, and eating.

As the death of her mother is the central event of the memoir, the book is divided into two halves: ‘before’ and ‘after’. While the same themes run throughout the book, regardless of the split, the first half concerns what it was like being raised by an abusive mother and features the majority of the ‘acting’ stories. You might expect the ‘after’ half to deal with grief— which is touched on several times— but it mostly shows the ripple effect of losing a childhood to TV and abuse. McCurdy lacks a sense of self, from constant acting both onscreen and at home, and struggles to understand who she is without her overbearing, controlling mother. It could be argued that the second half of the book focuses on the inevitable downfall, if McCurdy’s struggles with mental health hadn’t been interwoven throughout the entire book.

While the subject crops up several times in the early chapters, the latter half of the book focuses heavily on McCurdy’s lifelong battle with various eating disorders and her multiple attempts at recovery. Like so many before her, McCurdy’s poor relationship with food was learned from her mother, (“by teaching me calorie restriction, she was helping ensure my success”), and becomes a faulty coping mechanism after her mother passes away. This isn’t as uncommon as you might expect, as we often adopt or outright reject our parents’ habits, whether it’s a conscious choice or just a result of social learning. Growing up, my own approach to food quickly became skewed as a result of being raised by a mother who bounced between comfort eating and crash dieting, unable to process her own emotions in a healthy way. In Wasted, one of the most celebrated memoirs on eating disorders, Marya Hornbacher is encouraged by her mother (like McCurdy) to take up extreme dieting and notes that her anorexic grandmother thinks of meals as “an excuse for a few drinks”. Like many illnesses, eating disorders are genetic— but they’re also taught. McCurdy is only able to succeed in recovery by rejecting not just her own disease, but her mother’s, as well as the expectations that her mother had surrounding food, weight, and eating.

The development of anxiety, substance abuse, and eating disorders (all of which McCurdy struggles with) has also been linked to early experiences of abuse and interpersonal trauma. Joanna Iwona Potkanska, a trauma-informed psychotherapist, suggests that abuse results in losing a sense of self (“without Mom around, I don’t know what I want… I don’t know who I am”) and that the abuse is deeply internalised. A scene that particularly resonated with me was when McCurdy fled from a therapist, cancelled their future sessions, and blocked her number because she felt threatened that the therapist was getting too close to the truth. I’ve never spoken to a therapist about my abusive childhood, which has set back my healing process for years now because I blame myself for it. Potkanska says that this is a common response when abuse comes from a caregiver, as society puts parents on a pedestal and suggests that they can do no wrong. Or, if they do some wrong, it’s because they had no choice.

Abuse, especially when it comes from a caregiver, casts a long shadow over the rest of your life. (…) I was astounded by her ability to seek help from others and finally embark on the path to recovery.

This is the line that was fed to me and the same one that was fed to McCurdy. Her mother’s grave is inscribed with words like “kind, loyal, sweet, loving”. This was the same mother who called her a “whore” for having a boyfriend, who forced her into an unwanted career at the age of six, and (every time McCurdy was showered) conducted unwanted “breast and vagina examinations”, which McCurdy blacked out due to it being so traumatic. It’s no surprise that McCurdy finds herself (and her memoir) filled with anger, at everyone in her life, for canonising her dead mother as a saint. How could a parent have treated her like that? Why didn’t anybody help her? How did she grow up thinking that taking abuse was normal? I’m not surprised she’s angry. I’m angry too.

I’m Glad My Mom Died is a heavy read, to say the least, but I found myself unable to put it down for even a second— somehow, it felt like I was abandoning young Jennette in the same way that everyone else had. Despite only being in print for a few weeks, it has already become one of the most popular ‘celebrity’ memoirs to come out in years and has received warm appraisal from a generation of ‘forgotten children’ who find themselves or their families in her writing. While it touches on many themes, it feels to me like they always center back to McCurdy’s relationship with her mother and how it shaped the rest of her life: her unwanted career, her vulnerability to exploitation, and the eating disorders that could’ve easily killed her. Abuse, especially when it comes from a caregiver, casts a long shadow over the rest of your life. And while it might seem, from reading this review, that McCurdy is nothing more than a victim, I was astounded by her ability to seek help from others and finally embark on the path to recovery. There is nothing more difficult than stepping out of that dark shadow and into the light— but like everything else McCurdy throws herself into, (whether it’s acting, comedy, or writing), she succeeds.

Content warnings: emotional and sexual abuse, grooming, eating disorders.

Comments