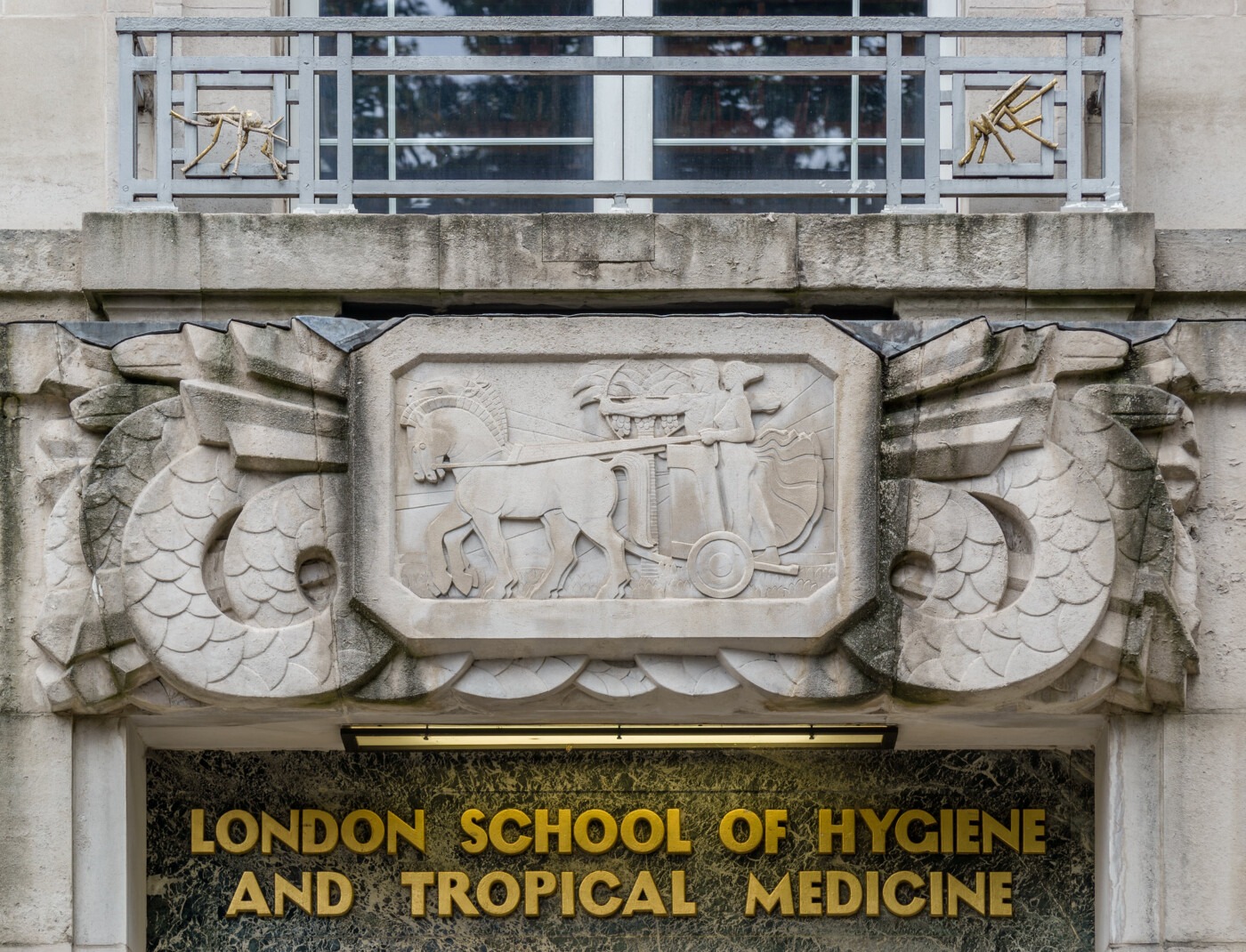

London medical school benefited from colonial exploitation, report finds

A report has found that the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) benefitted from colonial exploitation. It says that the development of “tropical medicine” at LSHTM was shaped by white supremacy and racist pseudoscience.

The initial and establishing funds for LSHTM were donated by an Indian Parsi philanthropist known as B.D. Petit. It relied on Britain’s colonies (particularly those in Africa) and colonial companies for funding. Despite this, its medical research only benefited white people.

The report explains that the original mission of the school aimed to reduce costs to British taxpayers for having to replace colonial officers who contracted (at times resulting in their death) tropical diseases such as malaria instead of aiding and improving the health of the colonised indigenous populations.

This meant that the school ran in close cooperation with the British government’s colonial office and helped to strengthen imperialism, said report author Dr Lioba Hirsch (from LSHTM’s Centre of History in Public Health). The study commissioned by the school itself argues that the development of tropical medicine can be attributed to white supremacy and racist pseudoscience such as eugenics. It details how senior staff publicly claimed that black and brown colonised people were both physically and mentally inferior to white people. LSHTM, being the main training centre for white doctors working in British colonies, then helped propagate such racist notions, the report notes.

It also follows the careers of the few people of colour that studied there in its initial decades. Many of the white students went on the become staff at the school. However, no students of colour were recruited until the late 1940s and 50s. For white students, studying at the school gave them the opportunity to serve with the West African Medical staff which from 1902 openly barred doctors of non-European descent. Students of colour were additionally segregated in their training, with senior staff expressing concern about them treating white patients in the 1920s.

Joseph Chamberlain, the secretary of state for the colonies, also encouraged medical officers in the colonies to send pathological specimens, materials and parasites to the school for teaching and research purposes often without consent from the patients. In addition to this, two London hospitals provided “native patients” from India, China, Japan and Goa.

Hirsch’s report also raises concerns about the medical ethics of the school’s founder, Patrick Manson, prior to the establishment of the LSHTM referring to an experiment conducted in 1877 that allowed others to prove the mosquito’s role in transmitting malaria. Manson used a Chinese man known as Hin Lo for his experiment, placing him in a hut where insects were allowed to feed on his blood as he slept. Manson conducted this experiment as suspected mosquitos to transmit the single-celled parasite that caused a tropical disease called elephantiasis. Hin Lo’s role in this has not been acknowledged by the school.

Referring to another independent review that uncovered structural racism at the institution in 2021, Hirsch said she hoped the school would issue an acknowledgement of the racist structures that contributed to its building and “that turned it into the intellectual powerhouse that it is today”. The review in 2021 had found that the institution’s colonial legacy continued to have a negative impact on the students and staff of colour and that leadership has been slow to act on issues of colonialism and racism.

Both the director (Professor Liam Smeeth), as well as the deputy director and provost (Professor Anne Mills) of the LSHTM, have commented on Hirsch’s report. Professor Smeeth said that the report “shows the reality of LSHTM’s colonial past” and also apologized to those who have been negatively impacted. Professor Mills added that they were committed to LSHTM “being a place of anti-racist education, employment, research and partnerships”.

Comments (4)

Very well written article. Enjoyed reading it .Interesting to see that Goa has a special mention along side INDIA. Thank you so much

Yet another revelation of ugly British colonial racism! Well researched and very well written.

Loved the content and flow of the article. Very well written and structured.

very well written. All points covered.