I am an activist, I am Spartacus: when everyone is an activist online, is anyone?

Posturing. Woke washing. Pandering. Clicktivism. It seems that people are finally aware that injustice is embedded into the foundations of our society, and they are now calling upon celebrities, and businesses to join in the fight against inequality. While this has led to greater awareness about issues such as sexual assault and police brutality, largely thanks to hashtags like MeToo and BLM, it has also led to a rise in self-proclaimed activists.

Many of these new ‘activists,’ are young members of Gen-Z, or as they have recently been dubbed, “Generation Anxiety.” To put this into perspective: if someone was to Google: ‘why is the world so…,’ the following adjectives would appear: miserable, unequal, and depressing. Following record breaking temperatures, a pandemic, and laws overturning fundamental aspects of human rights, it is unsurprising that people are not only feeling overwhelmed by the news, but also that they want to make a difference. After all, in a world that is changing in unprecedented ways, and not always for the better, striving for positive change can seem to be the only way forward for many people and businesses.

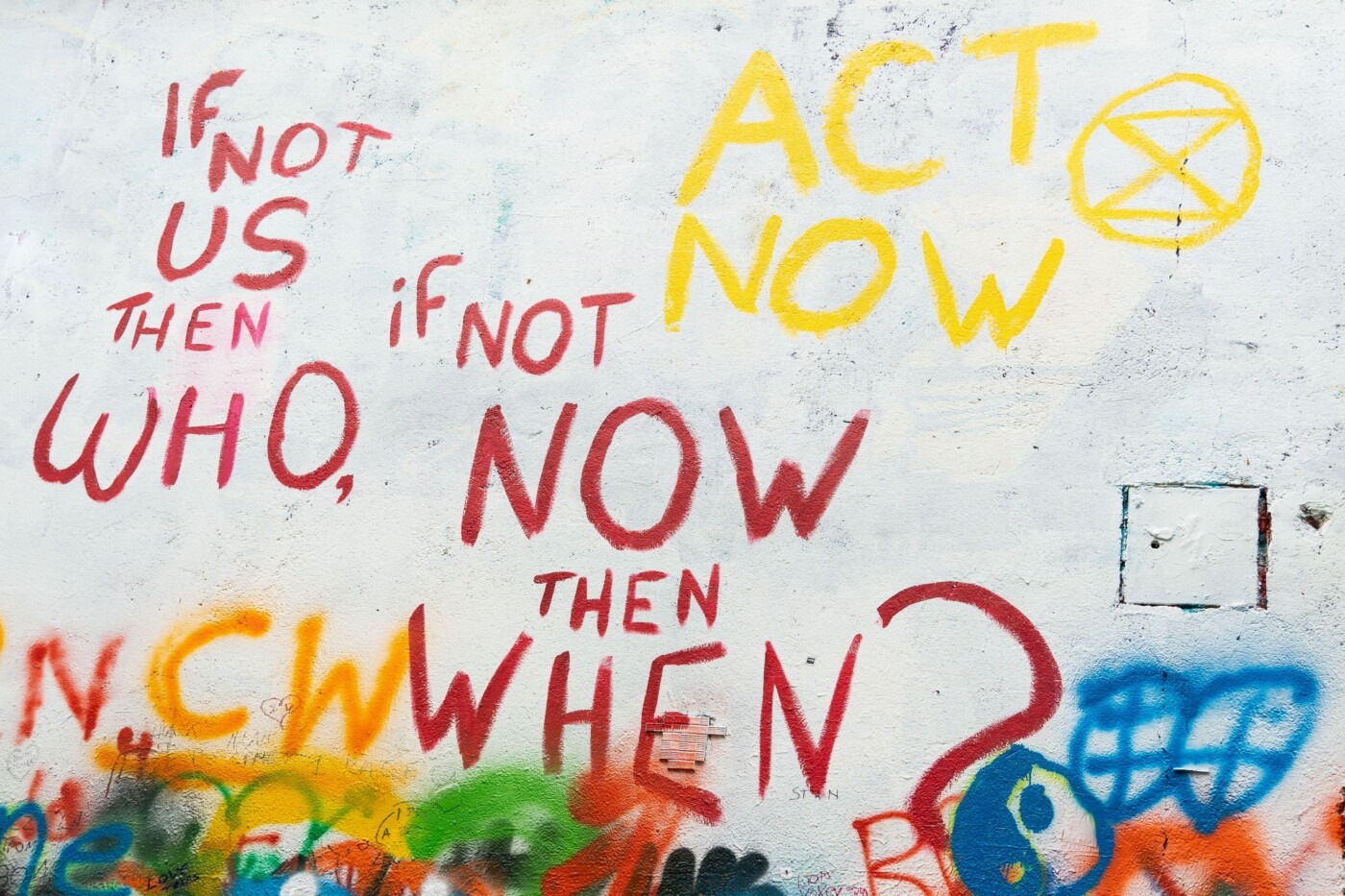

But this has caused a rising trend: across counties and industries, businesses are utilising social justice lingo to sell and advertise their products, such as Marks & Spencer’s ‘LGBT’ sandwich (a ‘woke’ twist on the classic BLT made especially for Pride Month). Likewise, more and more people are describing themselves as activists online. To put it simply: activism is now in. While this could mean that the world’s issues, that seem to be growing, are being identified, in both commercial and personal spaces, or even that the role of an ‘activist’ covers a complex multitude of identities and motivations, it is also raising questions. What does activism mean today, and who deserves the title of an activist? Should we all be one?

To many, the sacrifice of freedom, financial security, and even safety are all parts of the activist’s role.

One attempt to answer these subtle questions comes to us from the field of linguistics. The term ‘semantic broadening’ refers to words that can now be used to describe more things than they could in the past. And this term certainly applies to our understanding of activism in the 21st century. The definition of ‘activist’ has broadened over the last few decades, and some would argue that this shift offers hope to the younger generation coming of age in an increasingly polarised world, telling them that they can also make a difference.

One typical association of activism is that of camaraderie and strength. A visual demonstration of this would be the infamous ‘I am Spartacus’ scene in Stanley Kubrick’s 1960 film. Spartacus tells the true story of a Roman slave revolt led by the eponymous man. Decades later, it is widely considered a classic. Even those who are unfamiliar with the film may be familiar with the final scene: when a Roman General seeks out the leader of the slave revolt, expecting complete compliance, he is surprised to find brotherhood and deceit in its place. Rather than turn over the man that inspired them to fight for their freedom, the fellow slaves cry: ‘I am Spartacus.’ Of course, there was no way that every Roman slave was called Spartacus, but the insistence showed gratitude and courage, and to some, this scene reflects the solidarity that is seen in the landscape of modern political activism.

The actual actions of Spartacus screenwriter, Dalton Trumbo, echoed the solidarity he expertly captured in his script. In the forties and fifties, Hollywood blacklisted known communists, and Trumbo was imprisoned for his communist beliefs and his refusal to identify other communists. The professional punishment he suffered – struggling to find work under his real name – combined with the solidarity he displayed to his fellow communists, was emblematic of the job of an activist (despite falling short of the dictionary definition of vigoruous campaigning for social change). Similarly, Miriam Makeba spent decades in exile for her vocal disapproval of apartheid regime, Malala Yousafzai was shot for speaking out against gender inequality in education, and Judith Heumann set aside physical hygiene during a 24-day sit in, while fighting for disability rights. To many, the sacrifice of freedom, financial security, and even safety are all parts of the activist’s role.

Some find the insistence that anyone can be an activist anything but inspiring.

And this could be why the widespread use of the title ‘activist’ has sparked controversy. Some find the insistence that anyone can be an activist anything but inspiring, especially when considering the challenges and sacrifices other activists have to make for their causes. Many have condemned the broadening of this role, suggesting that the term has been watered down. Critics are worried that if ‘activist’ becomes an empty title, that anyone can award themselves with, then the original intent and impact behind these slogans will be lost. Some of the self-proclaimed ‘activists’ on social media may participate in demonstrations without necessarily recognising the gravitas of what they are doing. Critics are also concerned that members of marginalised communities could come to rely on said ‘activists’ only to find that their trust has been misplaced, and that the ‘activist’ in question does not have the capacity to meet their needs and enact change.

These arguments aren’t just theoretical. Earlier this year, an organisation founded by Academy Award winning actor Brad Pitt, reached a $20.5 million settlement with victims of Hurricane Katrina. Pitt’s foundation built dozens of affordable homes for those affected by the hurricane. This would have been another philanthropic gesture of Pitt’s. However, these homes had mould, rot, and termites. So, there are genuine risks when it comes to putting unqualified people in positions of responsibility. Brad Pitt is a highly decorated actor and producer, but an activist? When people decide to dip their toes in activism, it can appear like thay have simply jumped onto a bandwagon – one that they will eventually (and often pretty quickly) jump off of. In the face of activism being treated like a trend, Leina Gabra, in Zora Medium, suggests that people continue to challenge oppressive systems even when “social media inevitably moves on to the next viral news story.”

While an abundance of self-proclaimed activists can garner scepticism, particularly in an age where young activists have book deals, TED Talks and keynote speeches at the United Nations, this display of widespread discontent could actually become productive. Not just a case of absent-minded, bandwagon-jumping activism, but thoughtful online action. This online activism has led to real change before. For instance, there was an uptake in vote registration after several posts from notable celebrities. In Vice, Vote.org’s director of partnerships, Nora Gilbert, said that: “The impact is real. When we see Taylor Swift or Kylie Jenner or Rihanna post Vote.org stuff, we see the engagement on the platform.”

There is no glory in denigrating the work that online activists do because many people benefit.

Clearly, people from different professional backgrounds using their platforms to promote social change can be very effective. When people call themselves activists, it usually comes with the expectation that this person will use their resources to support marginalised communities. This might be via sharing Go Fund Me pages, posting infographics or even creating spaces online for discussion and transparency. There is no glory in denigrating the work that online activists do because many people benefit from the ways they use their platforms.

Social media, and online activists, have also supported people trying to enact change. For example, in 2016, when images of 13-year-old Zulaikha Patel went viral, as she, and her fellow students, protested alleged racist hair policies in Pretoria Girls High, the school removed the natural hair ban, following the pressure that had amounted online. While it could be argued that had every person who retweeted called themselves an activist, the cause would not have carried the same weight as Patel calling herself an activist. But it did show that people can show solidarity as part of a cause and help the process of enabling change.

Ultimately, social media is a valuable tool in activism. While people should describe their endeavours as activists to make it clear that they are seeking support from experts in the field, it would be hyperbolic to claim that the term ‘activist’ is cheapened by young people who call themselves activists on Twitter or Instagram.

Comments