The World of Yesterday Review – Memoires and nostalgia of a European

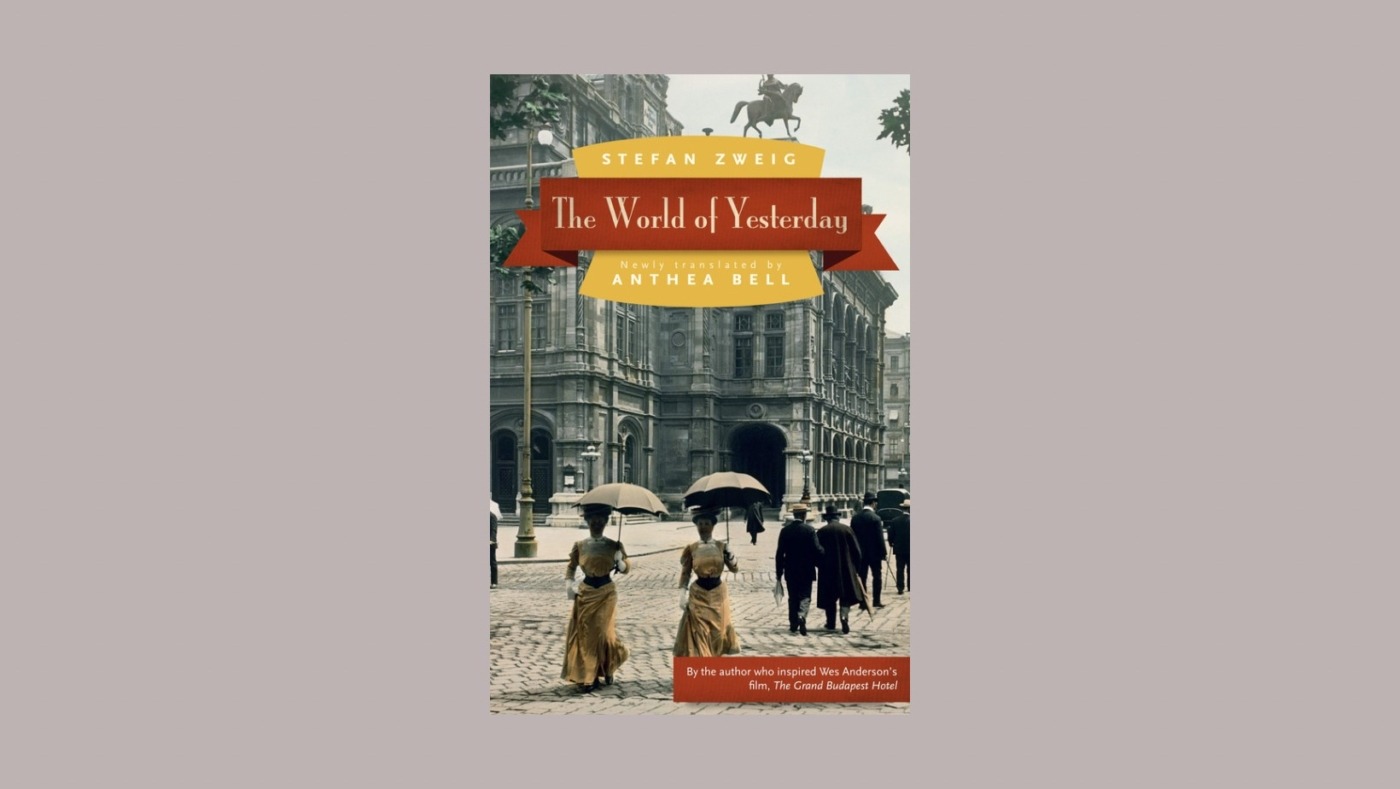

Stefan Zweig’s last work, which he wrote just before his death, is an account of the fall of a civilisation. A portrait of an era, from 1881 to 1942, it is a hymn to European culture, which he considers lost, eaten away by war and hatred. Stefan Zweig is very nostalgic, regretting an era of stability and freedom of thought, the golden age of security that collapsed with the First and Second World Wars. Thus, The World of Yesterday is not a personal testament, the reader will not find snippets of his intimacy. Zweig does not talk at all about the two wives he had and very little about his family. Instead, he captures the atmosphere of the great European societies – Austria, France, the UK, Germany, Switzerland, Russia, and Italy, among others – and the disasters of his time in a rich, detailed and classical style.

Stefan Zweig begins his story by evoking the Vienna of the good old days, at the end of the 19th century, when the city was oriented toward the most demanding artistic creation. This cultural dynamism was supported by the affluent, multilingual, and cultured Jewish bourgeoisie of which Zweig and his friends were a part. A perceptive observer, Stefan Zweig does not idealise all aspects of the world he regrets, which lends credibility to his view. For example, he is scathing about the school of the past, whose rigid and archaic framework prevented the free development of pupils. According to him, boredom stifled their best curiosities and intentions.

Even Zweig, the passionate anti-war man, had to admit that there was something impressive and exhilarating about this patriotic intoxication.

Stefan Zweig excels above all in describing the great events of his time. He paints a realistic and accurate picture of Hitler’s rise to power and the resulting gradual banning of the Jews. His writings on post-war inflation and living conditions – hunger, cold, destruction, instability – are also excellently written pages, rich in detail. What struck me most was the description of the atmosphere in the streets of Vienna after Austria entered the war. Processions formed, flags were raised, music resounded, young recruits marched in triumph, their faces beaming, and the Viennese crackled with joy as they passed. Even Zweig, the passionate anti-war man, had to admit that there was something impressive and exhilarating about this patriotic intoxication. This unique and paradoxical moment of fraternity is a terrible illusion when one knows the realities that the little Europeans will have to face.

I really liked the sense of proximity one has with Stefan Zweig. I had the impression that he was sitting right next to me, recounting his journey, his horror of violence. One can live through his eyes the events he describes. The effects produced by the Munich Agreement of 1938 on the population are a very good example. One can feel the appeasement of hearts made possible by the ‘’peace of our time’’. One can feel the relief of Londoners, refreshed and invigorated by Chamberlain. One can feel the hope created by the possibility of avoiding another inhuman massacre.

He sent the manuscript to his publisher the day before he committed suicide, wishing to preserve a trace of the world he cherished.

Another exceptional part for me is his journey in Paris. Indeed, I was born and raised in Paris, and I still live there; Stefan Zweig wonderfully transcribes the essence of Paris. When he writes that ‘’nowhere else could one experience the carefree life in a happier way than in Paris, made possible by the beauty of the forms, the mildness of the climate, the wealth, and the tradition’’, his words resonate with me.

Finally, the conditions under which The World of Yesterday was written add to the tragedy. Stefan Zweig wrote it in South America, after fleeing Europe, knowing that he would kill himself when he finished it. He sent the manuscript to his publisher the day before he committed suicide, wishing to preserve a trace of the world he cherished. His nostalgia for the golden age was too painful. He was consumed by the fall of the world of his youth, yet full of promise and destined for new progress. He would rather die than live in the present world, ravaged by war and fanaticism. The disarray is not only political but also personal. Throughout the 1930s, Jews were persecuted, and his plays were banned in Germany. His books fed the Nazi autodafés. The last shock he suffered was the withdrawal of his Austrian citizenship after the Anschluss. Although for almost half a century Zweig had trained his heart to beat like that of a European, a citoyen du monde, he nonetheless admits that when one loses one’s homeland, one loses more than a piece of land bounded by borders. The last line is upsetting, “only the person who has experienced light and darkness, war and peace, rise and fall, only that person has truly experienced life.” It can be connected to the letter he let after he committed suicide, ‘’I send greetings to all my friends: May they live to see the dawn after this long night. I, who am most impatient, go before them’’.

Comments