Experimental drug causes cancer to vanish in all patients

Taking the lives of nearly 10 million people in 2020, cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide. There are many different forms of cancer, with treatment efficacy varying from patient to patient. However, in a recent drug trial, the tumour disappeared in an astonishing 100% of patients.

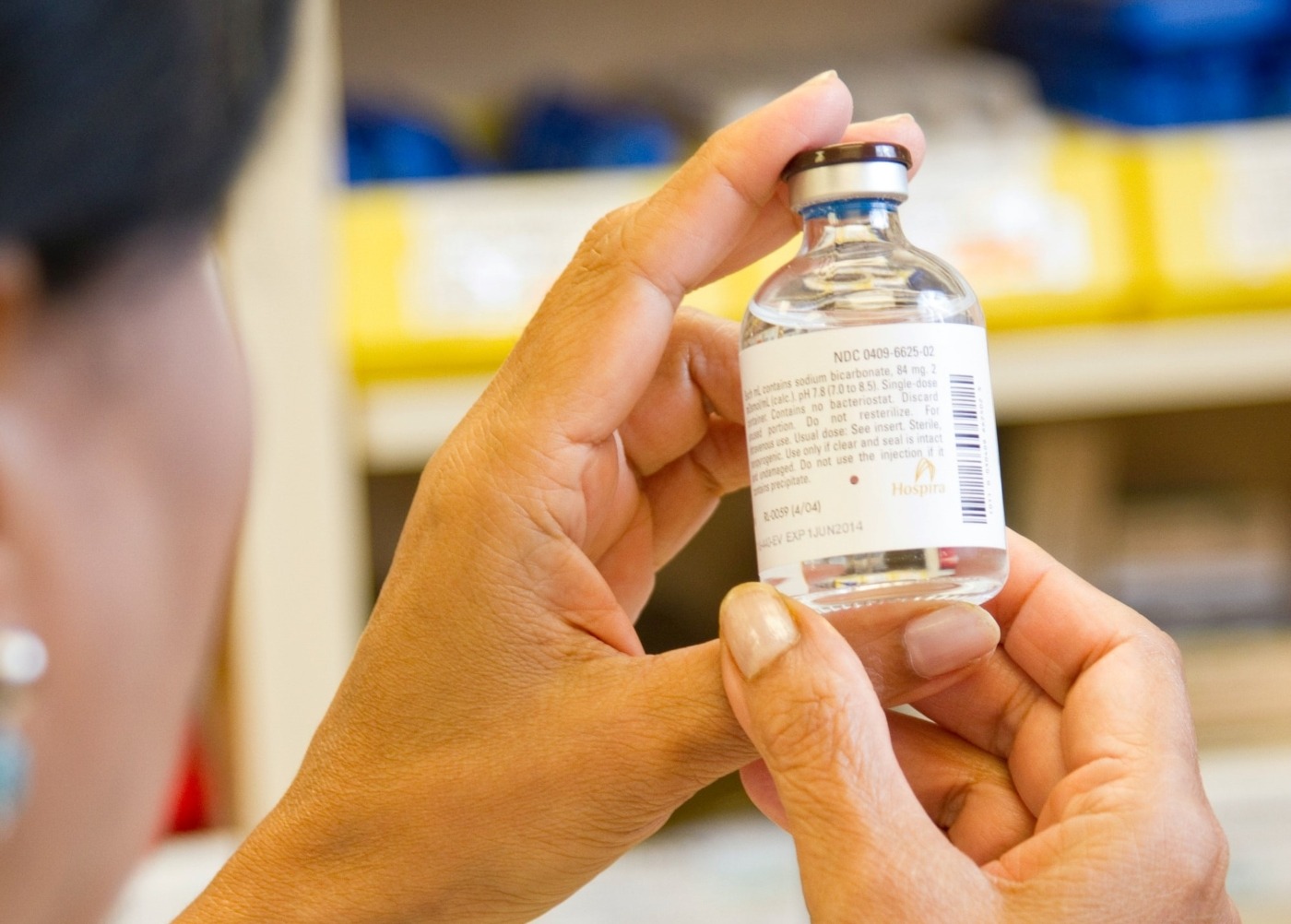

The trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, focused on 14 patients diagnosed with early stage rectal cancer. The treatment administered was in the form of a drug called dostarlimab. This drug acts by blocking a specific cancer cell protein that typically causes the immune system to withhold its cancer-fighting response. In other words, by blocking this protein, the immune response against cancer is not withheld and our cells can recognise and attack the cancer. Treatment was administered in nine doses over a series of six months.

A 100% success rate has previously been unheard of in cancer trials

Following the treatment, no traces of cancer were detected in all patients as confirmed by numerous scans, biopsies, and physical exams. This is an astonishing result as a 100% success rate has previously been unheard of in cancer trials. Furthermore, the patients did not require any further treatment and did not experience any significant complications or side effects.

Although rectal cancer is often survivable, especially if detected early, treatment for it has been far from ideal. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery can often lead to some extreme side effects for patients. In the case of rectal cancer, these can be permanent effects such as bowel and bladder dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and infertility. These complications can have a massive impact on an individual’s quality of life. Fortunately, such complications could all be avoided with the new drug.

The efficacy of this therapy on other forms of rectal cancer remains uncertain

The results of the drug trial are definitely remarkable, however, they do come with a few caveats, the biggest of which is the small sample size. The sample was diverse in age, ethnicity, and race, however, with only 14 individuals, it was definitely limited in size. Also, the treatment may not be applicable to all patients with rectal cancer. This is because the group chosen all had a specific abnormality known as mismatch repair-deficiency which prevents the body from repairing abnormalities in cells. This deficiency occurs in about 5-10% of all rectal cancer patients. Therefore, at this stage, the efficacy of this therapy on other forms of rectal cancer remains uncertain.

As the treatment is novel, we do not yet know whether the effects will be long-lasting or if the tumour will recur at a later date. The patients have been given the all-clear, but they will continue to be monitored for a number of years to catch any potential recurrences or spread of the cancer.

Overall, this trial is extremely promising and has the potential to change cancer treatment as we know it. We have already come a long way in terms of our understanding of the mechanisms of cancer and how it can be treated, however, this is the next step in finding effective treatment that can not only help get rid of cancer, but also minimise side effects on patients.

Comments