Last Night I Watched ‘Hardcore’

Oh my God, that’s my daughter.

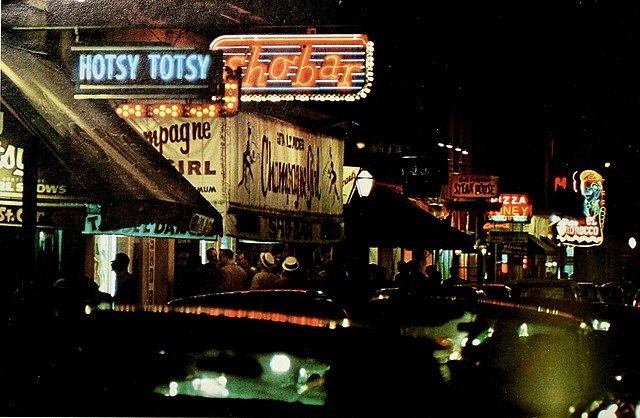

This simple tagline effectively conveys the premise, emotion, horror and angst of Paul Schrader’s inexplicably underrated drama Hardcore. Opening with images from a scenic, snowy Christmas day in the Midwestern American suburbs, Schrader introduces us to the close-knit homogenous Calvinist society of Grand Rapids. A series of smiling white middle-aged adults gather round in their nice tidy homes to set the dinner table, prepare their presents and cut the turkey. These people would never dream of missing their Sunday church service and they’re quick to make sure that their businesses are decorated with appropriately subdued colours. One such reserved but seemingly content Calvinist suburb-dweller is Jake Van Dorn (George C. Scott), a single small-business owner who lives with his teenage daughter Kristen (Ilah Davis).

After spending a picture-book Christmas with her father and close family, Kristen leaves Grand Rapids on a church field trip to California. Jake’s peaceful life is shattered when he’s told that Kristen has gone missing. After hiring an LA private eye (Peter Boyle) to look into her disappearance, Jake is shown footage of his daughter taken after her disappearance: she’s starring in a grainy 8mm pornographic film.

Schrader takes this undeniably intriguing premise and uses it to paint a fascinating portrait of a country undergoing a fundamental and irreversible cultural shift

At this point I’d forgive you if you rolled your eyes. You might expect that Schrader’s movie is a conservative backlash picture, where the righteous Reaganite Christian forces of the midwest roll into the liberal hippie coastal dens of depravity and rescue the innocent, powerless girl from her captors. Thankfully, Schrader is too strong a writer and too talented a director to make a movie that dull, simplistic and tediously conservative. Instead, Schrader takes this undeniably intriguing premise and uses it to paint a fascinating portrait of a country undergoing a fundamental and irreversible cultural shift.

Jake Van Dorn’s stable, quiet, Christian vision of American society is being challenged by forces that he doesn’t fully understand and cannot control. His daughter is a personification of the rebellious American youth of the 1970s: kids who were bored at church, stifled by conservative conformity and desperate to run off to LA and experiment with every kind of pleasure forbidden to them at home. Home is safe, but it’s suffocating; LA is dangerous, but it’s liberating. Jake Van Dorn’s daughter has chosen a very risky form of liberation, and Schrader unflinchingly shows us what happens when her father submerges himself in a culture that he despises.

The parallels with Taxi Driver (a movie written by Schrader) are obvious, but the clearest cinematic echoes here are The Searchers and Chinatown. As in John Ford’s iconic Western, we follow a dogged middle-aged man pursuing a young female family member living in an alien culture, and as with Robert Towne’s neo-noir story we see a man lost in a place that he cannot truly understand and surrounded by people who he cannot help. A particularly poignant moment sees Van Dorn browsing a sex shop, skimming his eyes over shelves of pornographic magazines, hoping to find clues to his daughter’s whereabouts.

We realise that we’re staring at an entire generation of people who broke from hundreds of years of conformist, conservative tradition

As the camera provides Van Dorn’s POV of the women occupying the magazine covers, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s tune ‘helpless’ quietly buzzes out of a shop radio. It’s a song about Young’s isolated childhood years in rural Canada and the band playing it are emblematic of the Californian countercultural scene of the 1970s. As we listen to the music and look at these young girls who have become pornographic models, we can almost read Van Dorn’s mind. How many of these girls are runaways from rural, Christian homes? How many of these girls are just like my daughter? We realise that we’re staring at an entire generation of people who broke from hundreds of years of conformist, conservative tradition. It’s a powerful, deeply evocative moment that captures the mood of a society rapidly undergoing profound change and it works because its power isn’t conveyed through clunky dialogue or an internal monologue. We get it all though music and imagery.

The best movies aren’t content with limiting themselves to a linear narrative. They reach for something greater by endeavouring to capture the spirit of their time and trap it inside the film can. Hardcore does this perfectly. In his search for Kristen, Jake meets a young sex worker called Niki and they agree to work together in locating Jake’s daughter. They share a series of conversations in which each lays bare their philosophies. Jake explains his Calvinism, telling Niki that all men are evil as a result of original sin, and that god has known from the beginning of time the few people on Earth that can be saved from their evil. Niki calls her own philosophy “Venusian”, telling Jake that sex isn’t important to her, so she doesn’t mind sleeping with lots of men. Here they have a strange point of connection. Sex is unimportant to Jake too.

Both are decent enough people, neither wishes harm on the other, but their relationship can only be temporary

As we watch this relationship develop, we see two people who represent completely different and opposing sections of American society meeting under heated and emotionally confused circumstances. Schrader doesn’t play this for cheap “we’re not so different, you and I” commentary. Instead, he recognises the sadness of their relationship. Both are decent enough people, neither wishes harm on the other, but their relationship can only be temporary. What can Jake truly do for Niki? Can he help her? Does she even need help? They are polar opposites, meeting by bizarre chance and destined for separation from the moment that they share their first conversation.

It’s this subtlety and intelligence that makes Hardcore a great movie. What other crime drama or movie about the porn industry explains Calvinist theology in great detail? What other mainstream American movie has a relationship this compelling and heartbreaking between two characters of opposite sexes with no hint of romance or shared ideology?

Schrader’s skill for creating characters with flawed but redeemable humanity and immersing them in a fascinating society shines through brilliantly here. Hardcore is a film about a torn and unbridgeable cultural landscape masquerading as a sleazy thriller about porn. After the credits roll and Van Dorn’s quest is finished, George C. Scott’s beleaguered face will stay planted firmly in your mind, and you’ll inevitably drift back to thinking about all those girls who never came home.

Helpless, helpless, helpless, helpless…

Comments