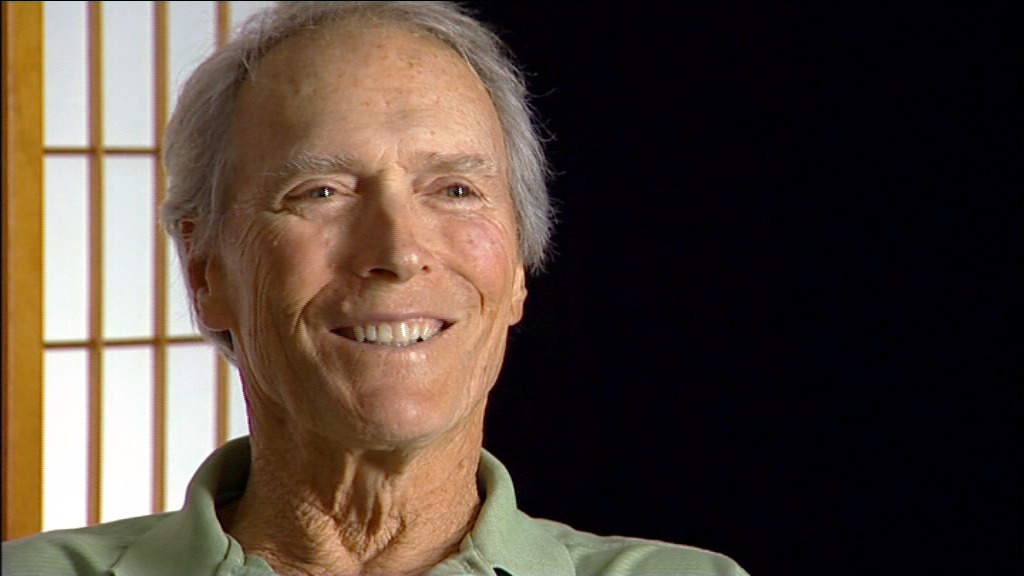

‘Cry Macho’ finds Clint Eastwood content with his last rodeo

Grace notes. They’re something the legendary John Ford used to speak of frequently when he made films, those magical moments that forgo plot in favour of pure feeling or emotion. It is only fitting, then, that Clint Eastwood, the closest we’ve ever gotten to an heir to Ford, has populated his 39th directorial effort primarily with grace notes. Cry Macho is a film of quiet moments, of people appreciating life as they have it, of being content with the time you’ve had… and the time you have left.

Based on the novel by N. Richard Nash, Cry Macho stars a 91 year old Eastwood as Michael Milo, an ex-rodeo star who retired after a back injury. He’s hired by former boss Howard (Dwight Yoakam) to travel to Mexico in order to bring back his 13 year old son Rafael (Eduardo Minett). After Michael finds him, Rafael’s mother sends men to follow and prevent the two from returning to Texas.

Cry Macho reveals itself to be a film happy to wallow in the small moments

If you’re expecting an intense, high octane thriller based on this synopsis, and as suggested by former casting choice Arnold Schwarzenegger, then that is not at all what Eastwood is interested in delivering. Instead, and frankly for the better, Eastwood delivers a leisurely Western with a sheer lack of plot urgency. Events happen as they please, and it’s not long before Cry Macho reveals itself to be a film happy to wallow in the small moments.

The majority of the film takes place in a small Mexican village – which Eastwood and director of photography Ben Davis refreshingly shoot without that irritating yellow filter that Hollywood assumes is the natural tint of Mexico – with Eastwood’s Mike basking in the delightful now: breaking horses as if he were a young man, taking multiple naps after hearty meals, and dancing with a pretty girl. It’s the latter in particular that holds a lot of the heart of the film, with Mike and Marta’s (Natalia Traven) relationship being almost wordless as the two do not speak the same language. Instead, their relationship is told wholly through gestures and glances, a suggestion that we could all use a little quiet and reflection in life, that the important things always find a way.

an image of Eastwood driving as a team of horses gallop alongside is a most poetic image of a man’s past

Of course, this being a Clint Eastwood film inherently suggests moments of self-reflexivity, as I heavily noted in my review of his previous film Richard Jewell almost two years ago, and Cry Macho could very easily venture into the realm of the greatest hits compilation: Eastwood’s interactions with the rooster Macho recall Eastwood’s natural chemistry with the orangutan Clyde in Every Which Way But Loose (1978), his status as an ex-rodeo star echoes Bronco Billy (1980), and an image of Eastwood driving as a team of horses gallop alongside is a most poetic image of a man’s past. Seeing an image of Eastwood don a cowboy hat on horseback is a pure crowd-pleaser, resulting in the sort of pleasure I assume fans of superheroes feel when they see Captain America interact with that raccoon, or whatever happens in those movies these days.

Granted, there is much joy to be had in watching a frail 91 year old Eastwood engage in fistfights and growl through his teeth (one example of this is highly reminiscent of his role as Harry Callahan), even if there is a consideration of melancholy here, that the old ways of masculinity perhaps aren’t the best – “This macho thing is overrated” he says to Rafael at one point.

Yet whereas The Mule (2018), the last Eastwood film in which he threatened to say goodbye, found its star/director self-reflexively repenting for past mistakes and, perhaps, unquestioned privileges, Cry Macho finds Eastwood reflecting on his life and being fulfilled with the life he’s had, appreciating the short time he has left. This is most evident in the aforementioned lack of plot urgency, but it is also clear in Eastwood’s controlled direction. His direction is economical yet precise, determined yet leisurely, a simplicity concerned with telling a story the same way the Classical Hollywood masters would.

One could argue that the film is an act of rumination on a dying genre and the death of the movie star

Shots of characters immersed in the landscape are at times pure John Ford, with one moment particular early on seeing Mike sat on a chair overlooking the mountains and valleys, layered as if the myths of the West were reality. So is a sequence whereupon Mike dances with Marta, light beaming through the window shades as if to confirm that romance can be found at any age – Cry Macho sure is an apt title in this scene’s case. One could argue that the film is an act of rumination on a dying genre and the death of the movie star, yet is there really much point in getting worked up over it when such calmness and moments of tenderness are available?

There’s a shot early on in Cry Macho, whereupon Eastwood, backlit against the setting sun, settles down on the ground to fall asleep. Gradually he lies until he eventually merges with the earth – a filmmaker and film star merging with his mise-en-scene, content with the life he’s lived, intending to keep going even though he understands his time may almost be up. The last of the great American filmmakers, there will never be another like Clint Eastwood. If this must be farewell, then Cry Macho is a fine farewell indeed…

Comments