The rise of NFTs in the art world- and what they mean

“We are the new avant-garde,” said Mònica Belevan, in a crowded Clubhouse chat, ahead of the launch of the flagship NFT auction by Accursed Share, a crypto art production studio, before describing the project as a new rebellion, a heist from the establishment, and the process of creating a new world.

For those who are unaware, an NFT, or non-fungible token, is a unique piece of data stored on a blockchain, which is a decentralised, peer-to-peer, data storage. Blockchain technology also lies behind bitcoin, but NFTs are not intended as an interchangeable form of currency. The art image itself acts as a sort of certificate-in principle – it relates little to the underlying technology. NFTs can thus utilise any image, be it an original work or a meme that has been viewed and shared millions of times.

Rather than seeing NFTs as a celebration of the commodification of art, many supporters view them as an opportunity to reclaim art

To outsiders, the idea might seem more than a bit mad. Why would people shill out eight-digit figures to purchase what is in many cases just a reproduction of a visual anyone could copy online? An easy response to this might be that in what social critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin called the “age of mechanical reproduction.” It has always been possible to make cheap duplicates of famous art. You can download the Mona Lisa, print it up, and stick it on your wall at practically no cost. So paying top dollar for an NFT of, to list one example, “Charlie Bit My Finger,” might not seem entirely unreasonable within an art world pure rationalists could always write off.

Rather than seeing NFTs as a celebration of the commodification of art, many supporters view them as an opportunity to reclaim art, in a sense, by commodifying it ahead of its commodification by stagnant, mouldy, centralised institutions.

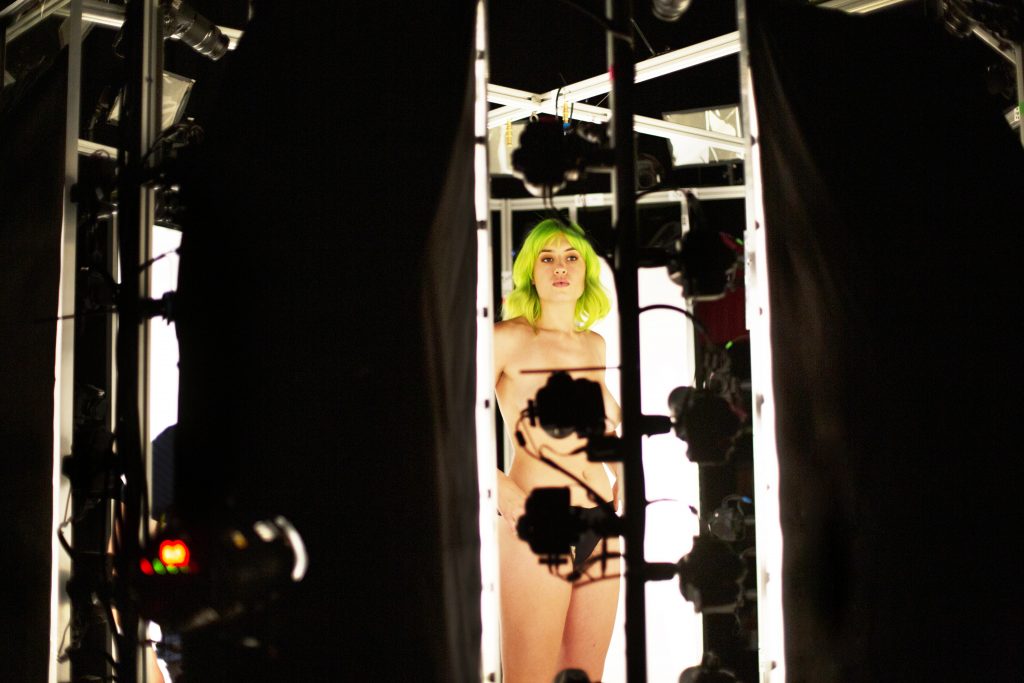

It’s the same ethos, many of them say, behind WallStreetBets, the amateur investor craze that disrupted financial markets earlier this year by pushing up the value of GameStop and other stocks. Accursed Share’s first project (named after a book by Georges Bataille), Curse NFT, was based on the image of Krystall Schott, a young woman whose photo has been the number one image that you would see if you searched for ‘face’ on Google. In creating a gorgeous piece of digital art of Schott’s face and selling it as an NFT, Schott was able to “reclaim” the rights over her digital body as a form of intellectual property. In the end, the NFT sold for approximately $31,300 (about £23,000). However, if that sounds like a lot, NFTs have exchanged hands at totals many times higher.

It’s not surprising, then, that this form of art took off at a time when many museums were still closed due to coronavirus

Probably the most famous NFT creator is Beeple, whose work ‘Everydays – The First 5000 Days,’ sold earlier this year for a cool $69.3 million (£50.8 million). That’s the sixth-highest total ever paid for a work by a living artist. The major money being exchanged has forced both the art establishment and the conservative financial press to pay attention whether they want to or not.

In an article in its magazine, the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan featured an interview where NFTs were described as “the triumph of a kind of hedge-fund thinking”, but at a more intriguing and challenging level, as part of the increasing abstraction of our lives, as distinctions between virtual and physical reality are increasingly blurred.

It’s not surprising, then, that this form of art took off at a time when many museums were still closed due to coronavirus, in-person art auctions were severely restricted when not entirely cancelled, and with work, school, and shopping moved online, everyday life had become ‘gamified’.

Whether NFTs represent an innovation in artistic insight is another question entirely

Already, The Wall Street Journal has reported that websites like DeviantArt have taken steps to safeguard against NFT infringement, and there has been a myriad of fraud attempts surrounding them. Beyond the predictable criticism of being yet another speculative asset class for globalist billionaires to dump their earnings into at a time of record inequality, NFTs have also raised other concerns. Like bitcoin, the blockchain technology underlying NFTs demands copious energy, and therefore, environmental pollution.

NFTs still may end up as a flash in the pan, or be subject to massive fluctuations, like bitcoin, before they arrive at a relatively stable and predictable price. It’s still hard to see an institution like MoMA, or in the UK, the Tate Modern, shelling out millions of dollars to purchase a digital image that has been reproduced everywhere. But then, these same institutions gave credence to Duchamp’s “readymades” and Andy Warhol.

NFTs may thus have a bright future ahead of them as a novel asset class, and might even one day appear in the acquisition lists of major museums. Whether NFTs represent an innovation in artistic insight is another question entirely.

NFTs, like any other art form, will arguably need to provide something new in a message

If you interpret the “meaning” of an NFT as a commentary on the commodification of art, NFTs arguably just repeat the message, more than 50 years after the fact, of Warhol and Pop Art, to which they bear more than a passing resemblance. Camille Paglia, the lightning-sharp lightning-rod thinker on art and gender, said that Warhol, despite being her hero, “killed the avant-garde” by incorporating into it the imagery of consumerism.

As life becomes increasingly commodified, predictable, and sterile, NFTs, like any other art form, will arguably need to provide something new in a message, not just medium, if they are to prove this maxim incorrect.

Comments