Separating art from the artist

Questions of morality prove themselves to be so enriching and exciting, to me at least, precisely because they are the guiding force for how humans can live their best life. For many across the world, that morality comes from a faith in God. For me, I am guided by humanism and a strong belief in the potential for humans to make their own situations better, regardless of a need for a deity.

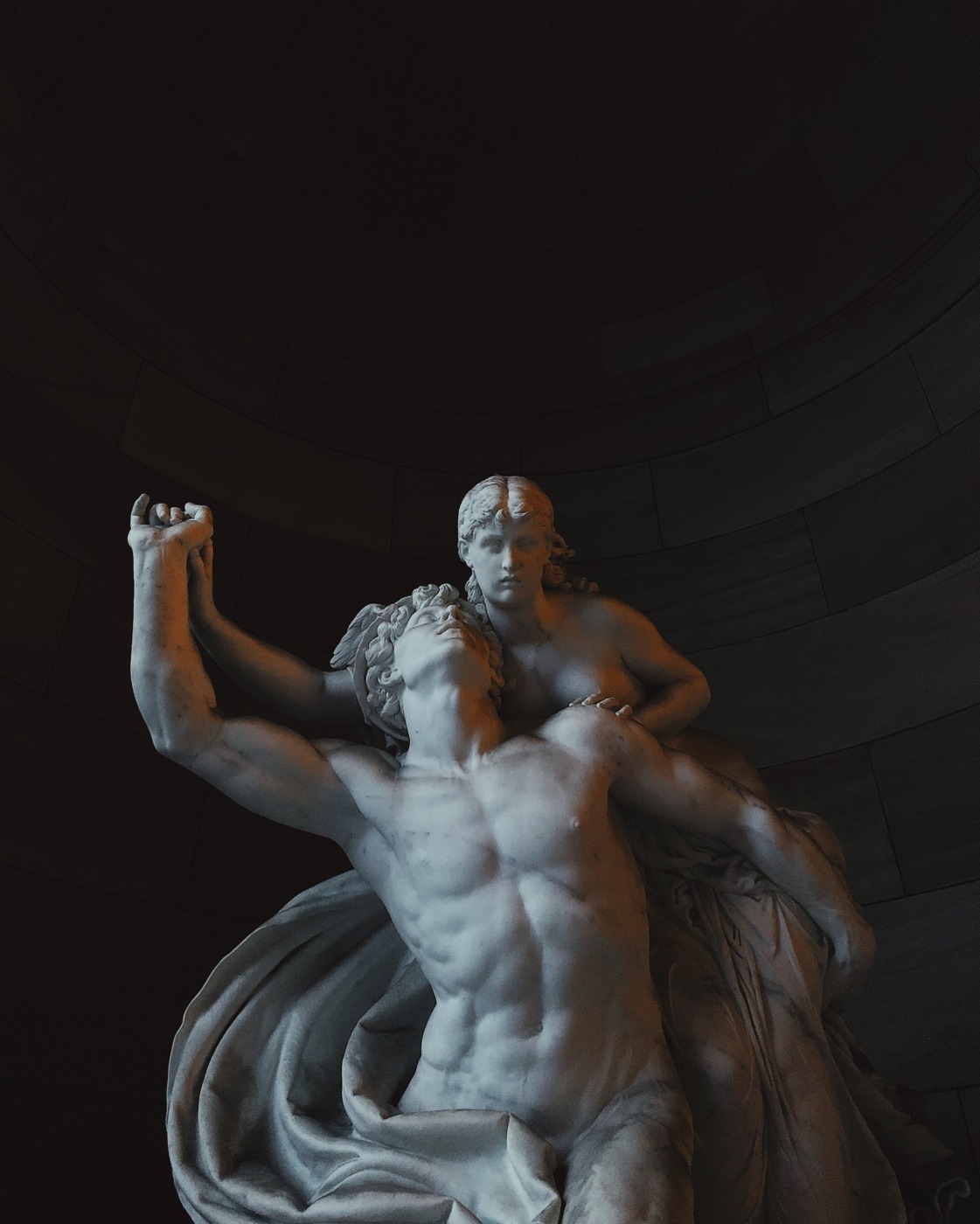

One of my favourite moral questions is about art. To define art, what art is, means you’d be writing a book that never ends. Its definition and examination is something scholars have and will continue to explore for millennia. Often, artistic creations relate to how humans seek to express something to others and pinpoint their view on the world.

Can we separate loving artistic creations while also loathing the individuals who made such pieces of work?

All of us enjoy art, be it music, films, TV programmes, paintings, sculptures, dance, architecture. We each experience cultural creations every single day. But what happens when the individual who created that art turns out to be a monster? What if they’ve made controversial political remarks? Who defines what is controversial? There then comes the question of whether we can separate loving artistic creations while also loathing the individuals who made such pieces of work.

That was the question tackled one cold Wednesday evening in Central Coventry by the Battle of Ideas. The organisation are holding a weekend of debate in London (where I shall be stewarding) but had also set up a satellite event here in the Midlands. My love of art, politics and ideas meant attending this discussion required no debate, something that is an exception when it comes to the Battle.

That an individual artist may have made some wicked remarks should not detract from the fact that their art, which could be completely unrelated, remains superb.

The general consensus in the room was that we should wish to separate the artist and art wherever possible. Why? Because awful people can sometimes make utterly divine pieces of art. That an individual artist may have made some wicked remarks should not detract from the fact that their art, which could be completely unrelated, remains superb.

Indeed, the debate was raised over what kind of art humans could value if we also held the artist up to immensely high standards. Artistic creators could perhaps remain the preserve of, bluntly, boring individuals who have no eccentricities or nothing of substance about them. The discussion involved a celebration of exceptionalism in art as a worthwhile end and something to celebrate, regardless of the creator themselves.

Where it becomes far harder is if the artist has committed a crime for which they have never been held accountable.

I found the conversation riveting with regards to separating an artist’s words and political views from any illegal actions committed. For example, an artist might have political views I deplore, but I still should be able to appreciate their art from that.

Where that becomes far harder is if the artist has committed a crime for which they have never been held accountable. The Oscar-winning film director Roman Polanski, for example, has been able to evade justice for his crimes in the late 1970s by living in Europe. That’s allowed him to carry on making films, with those who work with him choosing to suspend any kind of moral judgement on working with him. If I was to ever watch his films, I would always regard them as morally tainted.

There should be a celebration that artistic judgement – both of the art and artist – can only come with artistic freedom.

Some argued that separating the art from the artist was undesirable, for it was precisely who the artist was which so affected the art they went on to create. For example, the poet Phillip Larkin is often criticised for his immensely regressive views and socially conservative attitudes. Yet were they what made his poetry so interesting and riveting in the long term? That is a question up for debate.

The most important point I felt was made was the need to avoid any kind of censorship. While I will always deplore Roman Polanski, I would never campaign for his films to be censored. I view other artists who may have committed far lesser offences, or just have a different point of view to me, in a similar manner. Instead, there should be a celebration that artistic judgement – both of the art and artist – can only come with artistic freedom. In a society that calls itself free, individuals should not be deterred from making their creations and also knowing the public are individually entitled to have whatever view on the culture they like.

Comments