The science of stress

The stress response might be more familiar to you as the “fight-or-flight” response, and occasionally makes headlines when people perform incredible physical feats under pressure, such as lifting cars to free someone trapped underneath, or even fighting off a polar bear.

To put this into perspective, the record for a raw deadlift (i.e. without aids such as lifting straps) is 460 kg, however there are news reports of ordinary people lifting up to three times that much in life-threatening situations. Although the actual weight lifted in these circumstances is greatly exaggerated in these reports (the car is at most lifted a few inches off the ground, with three to four of its wheels supporting the majority of the car’s weight, meaning that the actual weight lifted by the ordinary person is closer to a few hundred kilograms as opposed to thousands), these incidences display the impressive effects that the stress response can have on the human body.

The sensations in our bodies that we recognise as “stress” are due to the release of the hormones cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline from the adrenal glands. As the adrenal glands are located behind the stomach in the abdominal cavity, the release of stress hormones can produce the familiar feelings of butterflies or knots in the stomach. Fluttering sensations are due to the increased sensitivity of the nerves in the abdominal smooth muscles in response to adrenaline, whereas at even higher levels of stress, electrical impulses will stimulate the muscles to contract more strongly and frequently, resulting in uncomfortable or painful cramps.

Other symptoms of stress include insomnia, a rapid heartbeat, tense muscles, nausea, and digestive problems as blood flow to the digestive system is redirected to the muscles.

By default, our bodies are programmed to respond with pain and fatigue when we have reached our safe physiological limits, which is about 60% of our potential muscle recruitment. However, in times of extreme stress this safety mechanism is temporarily suspended, allowing us to recruit up to 100% of our muscle fibres. Obviously, this comes with a high risk of injury such as muscle tears, which is why this only occurs in perceived life-threatening situations to ourselves or others.

The stress response is our physiological and psychological reaction to real or imagined fear of harm to ourselves or to other people. In the 21st century, we are less likely to encounter physically dangerous situations than in our evolutionary past when being eaten alive was a constant threat. However, as you will be aware this isn’t the only trigger for the stress response.

The stress response is our physiological and psychological reaction to real or imagined fear of harm to ourselves or to other people

As highly social animals, we are acutely sensitive to other people’s reactions and opinions, and the stress response can be elicited by a fear of failure, embarrassment or ostracism. As such, an important exam, a presentation, or a job interview can elicit strong stress responses as well, despite there being no physical danger present.

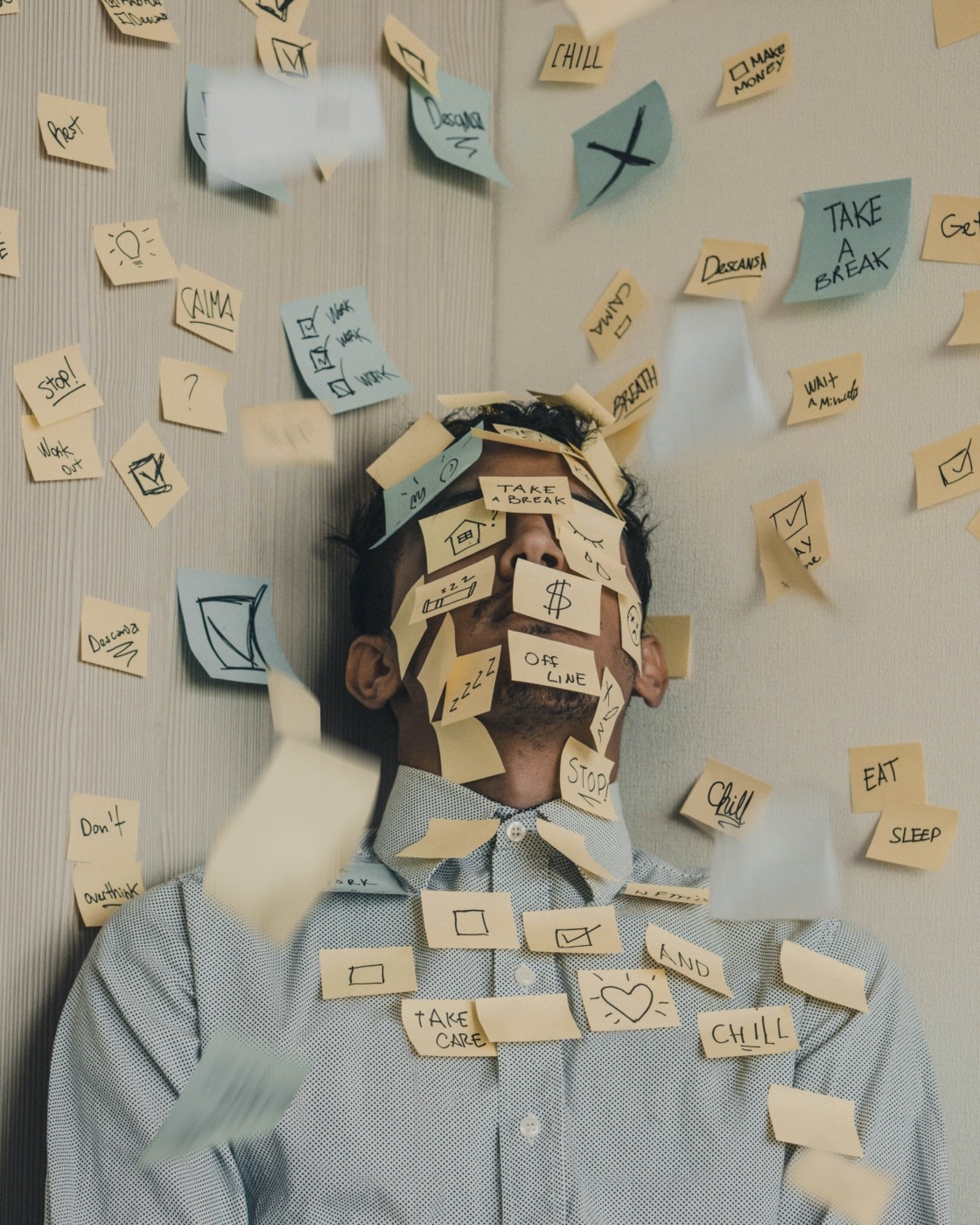

Stress can be beneficial, helping you focus and think fast on the spot. However, when stress levels don’t return to normal it can have very negative consequences for our physical and mental health.

Stress can be beneficial, helping you focus and think fast on the spot

The stress response evolved to provide a short-term burst of additional energy when the body most needs it. By definition, being in a stressed state for long periods is not sustainable, as you deplete your energy reserves faster than they can be replenished. Chronic stress puts a lot of strain on the body, causing and exacerbating mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. This can lead to weight gain, disrupt normal digestion and sleep, and increase the risk of heart disease. It can also lead to aches and pains in the chest area and in tense muscles as they struggle to relax.

As the exam period gets into full swing, it is more important than ever to allow yourself to relax. Taking breaks and relaxing are important parts of a healthy lifestyle and can help productivity by preventing burnout. Remember to exercise, eat healthily, get outside, and take time for things you enjoy. Why not watch your favourite Netflix show at the end of a long day or meet up with a friend? Your body and mind will thank you for it.

Comments