Childhood, identity, and the music that makes you: an interview with Pete Paphides

Most memoirists treat their childhoods as inconsequential. What really happens to you in the first ten years of your life, when your worries are minimal – no bills, no career to forge, no marriage to maintain – and you’re tied to your parents, limited in your explorations of the world? What is there to document other than running around the garden, jumping in puddles, or drawing on the walls?

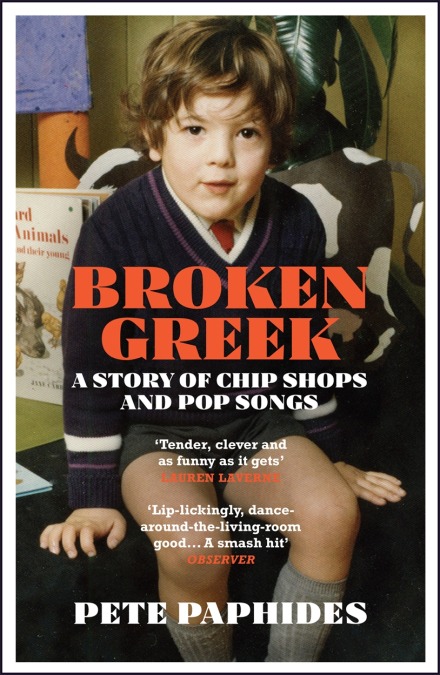

Pete Paphides, however, is not most memoirists, and his book Broken Greek is not like most memoirs. Indeed, his childhood was not like most childhoods – between the ages of four and seven, he stopped speaking to anyone bar his own parents. He was an anxious child, fearing tall buildings and Rod Hull puppets amongst other things, and quietly made plans in case his parents ever abandoned him.

All these records I love, the reason I love them, is because they were helping me to figure out who I was

– Pete Paphides

Even for memoirists who have had more ordinary childhoods, for Paphides, the idea that childhood isn’t worth documenting is flawed. “Those first ten years of your life [are where] the main building work on your personality is happening,” he argues. “It always surprised me that when you read a lot of memoirs, those are the years that writers seem to whizz past – they deal with it in half a chapter, or something. Those are the years I want to know about. Eighty percent of the reason why you are the way you are is because of all the stuff that happened in the first ten years of your life.”

The influence of this perspective in Broken Greek couldn’t be clearer – Paphides devotes close to six hundred pages to just seven years of his life. We never hear about his three-decade-long career in music journalism, but Paphides shows us what paved the way for it in the form of an evolving and ever-growing “obsession” with the pop music of the 1970s and early eighties, nurtured by Top of the Pops and Dial-A-Disk (ask your parents). “I wanted to celebrate this amazing period in the history of pop music that I was lucky to come of age in,” he says. The young Paphides is a witness to the days where David Bowie was a breakout star, the private lives of the members of ABBA were public business, and the UK was actually good at Eurovision (he latches on particularly to the 1976 edition’s winners, Brotherhood of Man). They are described with remarkable vividness for events that took place close to fifty years ago, especially when their impact was preserved in the still-developing memory of a child.

Equally, Broken Greek is a celebration of the wonder that music inspires that sometimes bypasses words, especially when you only have a child’s vocabulary to articulate it. Part of the joy of writing this memoir, Paphides says, was to convey the emotions of a child with the hindsight and vocabulary of his adult self. “I could remember how I felt about things, but I didn’t necessarily have the vocabulary,” he comments. He returns to the example of Brotherhood of Man winning Eurovision with ‘Save Your Kisses For Me’: “I wanted to write about it with the intensity that a lot of people might write about seeing David Bowie doing ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops – in its own way, it was just as intense. I felt like they were beckoning me from the TV screen. I wanted to portray that scene as epiphanic.”

Indeed, Paphides is the first to admit that Broken Greek is “two books in one,” both a childhood memoir and a personal history of the music he was growing up with. The narrative slips between accounts of particular events in Paphides’ life, and dissections of particular songs or albums in the register only a seasoned music critic could possess, infused with the wonder of his child self discovering it. “I [couldn’t] tell the story of one without telling the story of the other,” he explains. “The music was what I felt was explaining my situation. All these records I love, the reason I love them, is because they were helping me to figure out who I was.”

Finding an identity was a process complicated by his family background and their circumstances. Paphides was born to parents from Cyprus; his family was part of the influx of immigration into Britain during the 1970s from all corners of the world, from Bangladesh to Jamaica. Hoping for a better life, his parents left their then war-torn homeland for the Acocks Green area of Birmingham. They opened a fish and chip shop and lived upstairs, and it is this setting that forms the backdrop of Broken Greek.

Since the referendum, it’s been very easy for a lot of people to succumb to a slightly dehumanising perception of people from other countries

– Pete Paphides

The family returns to Cyprus at various points across the book, the question of whether they will go back occasionally rising to the surface. Despite his Cypriot heritage, however, young Takis feels the pull of British culture more strongly, with his ability to speak his native Greek becoming weaker (or ‘broken’, as is the book’s title), and he later changes his name to the more anglicised Peter. “If your parents are from another country to the one you were born in, then you’re always going to have some kind of questions of what your identity is,” Paphides observes. “I surely can’t be the only person because millions of people who grew up in this country, whose parents came from abroad, I imagined they must have gone through a version of the same thing.”

The book has certainly resonated for this reason, but it becomes particularly poignant considering that it has arrived in the aftermath of Brexit and the growth of xenophobic sentiment since the referendum – those who came to the UK looking to contribute to the economy and build a better life for themselves are now dismissed as a drain on resources. “Since the referendum, it’s been very easy for a lot of people to succumb to a slightly dehumanising perception of people from other countries,” he says. “Inadvertently, it’s kind of serendipitous in a way if that book plays just a small part in reminding people that the story of every person that comes to this country is a human story.”

For all the changes we go through, from childhood to adolescence to adulthood, there are some things that remain constant. “I haven’t changed that much,” Paphides acknowledges. “When I’m in a café, I probably order the same things I probably would have ordered when I was nine years old. I never travel anywhere without a capsule of concentrated squash.” And of course, he’s just as obsessed with music. The DIY music magazine he describes his ten year old self making becomes an endearing moment of foreshadowing by accident, to any reader familiar with the adult Paphides’ career in music journalism. Paphides says he doesn’t really keep up with what is in the Top 40 week by week, but still keeps up with what’s coming out. “I’ve been playing the Dry Cleaning album [New Long Leg] to death. I do like the music young people with guitars [are making] – there’s a certain kind of energy that you get with a young band that doesn’t hang around long.” Two years ago, he created a record label, Needle Mythology, which largely presses vinyls for albums that never got a proper vinyl release.

Paphides has “a couple of ideas percolating” for future books, and doesn’t rule out writing a sequel to Broken Greek that would chronicle other parts of his life. However, he’s not in a hurry. “I just like writing short pieces about music, enthusing about new records. I was fifty when [Broken Greek] came out. I’m just going to take my time.”

Comments