Why classic literature shouldn’t be consigned to the history books

Society’s assessment of the literary canon is an important indicator of what books it believes children should understand. It also relates to what purpose we hold the education system to – as a tool for enlightening children, presenting them with information from the past, and trying to improve their critical thinking abilities within contemporary society. Given that education must always be about far more than simply an approach to gaining employment, enlightening children with knowledge from the past is a vital aspect in ensuring the education system fulfils its purpose.

Learning about different books from historical and contemporary times is a key part of this process. Of course, factual historical events frame understanding within the minds of individuals for assessing their progress and making sure their understanding is adequate. Only by learning about the past is it possible to shape the future. However, history, the brilliance of writing, innovative ideas, and learning about the important figures that make up the past is just as essential and possible within English writing.

Shakespeare’s plays cover all of the human emotions and ideas: love, betrayal, hatred, fury, and revenge, to name a few

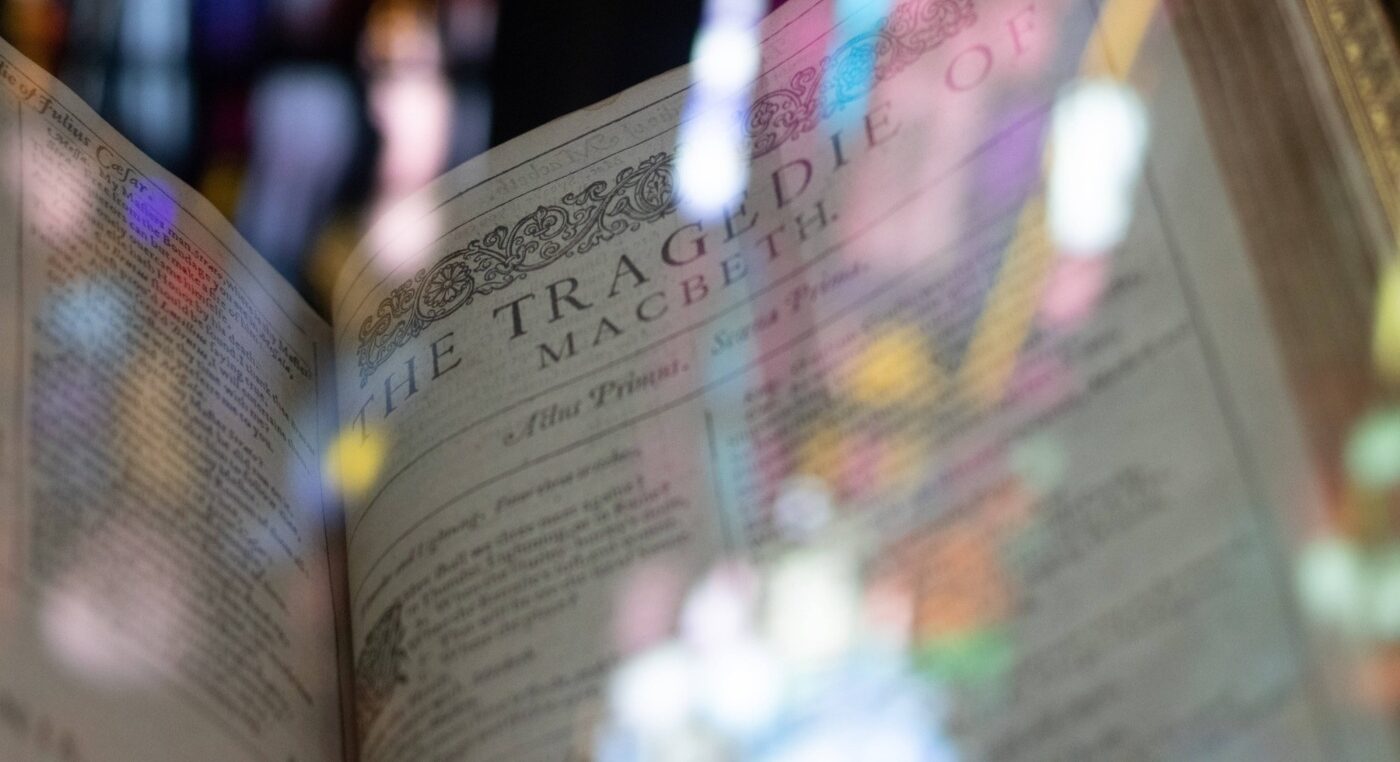

Shakespeare is probably the most archetypal historical figure contained within political and literary analysis. Given that his plays are compulsory at GCSE, analysing Shakespeare forms a key part of every person’s learning. With this study can easily come criticism. Specifically, what relevance does Shakespeare have today? Isn’t it time he was consigned to the history books, allowed to gather dust like so many other historical figures?

My reply: absolutely not. Though the language is antiquated, this is part of the brilliance and interest found when learning about his plays. It’s possible to see both how people spoke then, and also how language has subsequently developed. Similarly, many of the words we use today, including bandit, critic, lacklustre, and lonely, were invented by Shakespeare. A figure of such significant lexicon deserves recognition. Shakespeare’s plays cover all human emotions and ideas: love, betrayal, hatred, fury, and revenge, to name a few. These characteristics are as much a part of who we are as humans today as they were in the 17th century.

While the history books can reveal certain aspects, it is fiction that provides the comprehensive detail and ideas for this change

A similar trend can be seen regarding other authors that are historically studied. Charles Dickens, for example, is famous for his exploration of Victorian London. Nobody can accuse him of holding back on highlighting the widespread inequalities, poverty, and destitution within society at the time. However, the brilliance of his writing comes from such descriptions that take readers into a location they could have never possibly visited.

That is one of the fantastic things about literature: revealing what has, and hasn’t, changed within a society. Even an area that seems remarkably similar and unchanged by the forces of history will have been altered throughout time. While the history books can reveal certain aspects, it is fiction that provides the comprehensive detail and ideas for this change. It is just as relevant in the works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Susan Hill, and J. B. Priestley, all fine writers.

One of the disappointing things about the proposed evolution of GCSE English Literature has been the removal of American writers from the syllabus. The words of John Steinbeck, not least in Of Mice and Men, are a universal and important message that schoolchildren deserve to hear. Moving the focus towards solely British writers is reductive and narrows, rather than expands, the range of choices on offer to children.

The situation is slightly better at A-level. I studied English Language and Literature, which gave me the opportunity to read one of the greatest novels of all time: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. First published in 1925, it gives an excellent insight into the Roaring Twenties, and so ominously foreshadowed The Great Depression. Similarly, I also read Arthur Miller’s All My Sons. One of Marilyn Monroe’s many husbands, Miller’s examination of the conflict between family and societal loyalty is something that the generality of the textbook could not have matched.

The best writing should be about the importance of ideas and history. Exploring this in both historical and contemporary writing is not mutually exclusive. Similarly, recognising the need for this approach to be global is also important and essential. The literary canon of centuries gone by can teach the children and learners of today so much. The same is true for contemporary fiction published in the last year, potentially shortlisted for the Booker Prize. A zero sum game of what fiction deserves to be read helps nobody, and only hinders what the true reading experience should offer.

Comments