The science behind biofluorescent animals

While lockdown may have put the increasingly eccentric variety of laser lights at nightclubs on hold, a few animals can still throw a rave of their own. Recently, a team of researchers, from Northland College in the USA, discovered that two species of rabbit size rodents called springhares have the ability glow under black light. They are the newest member of an increasingly diverse biofluorescent club, a group of organisms that has long fascinated biologists.

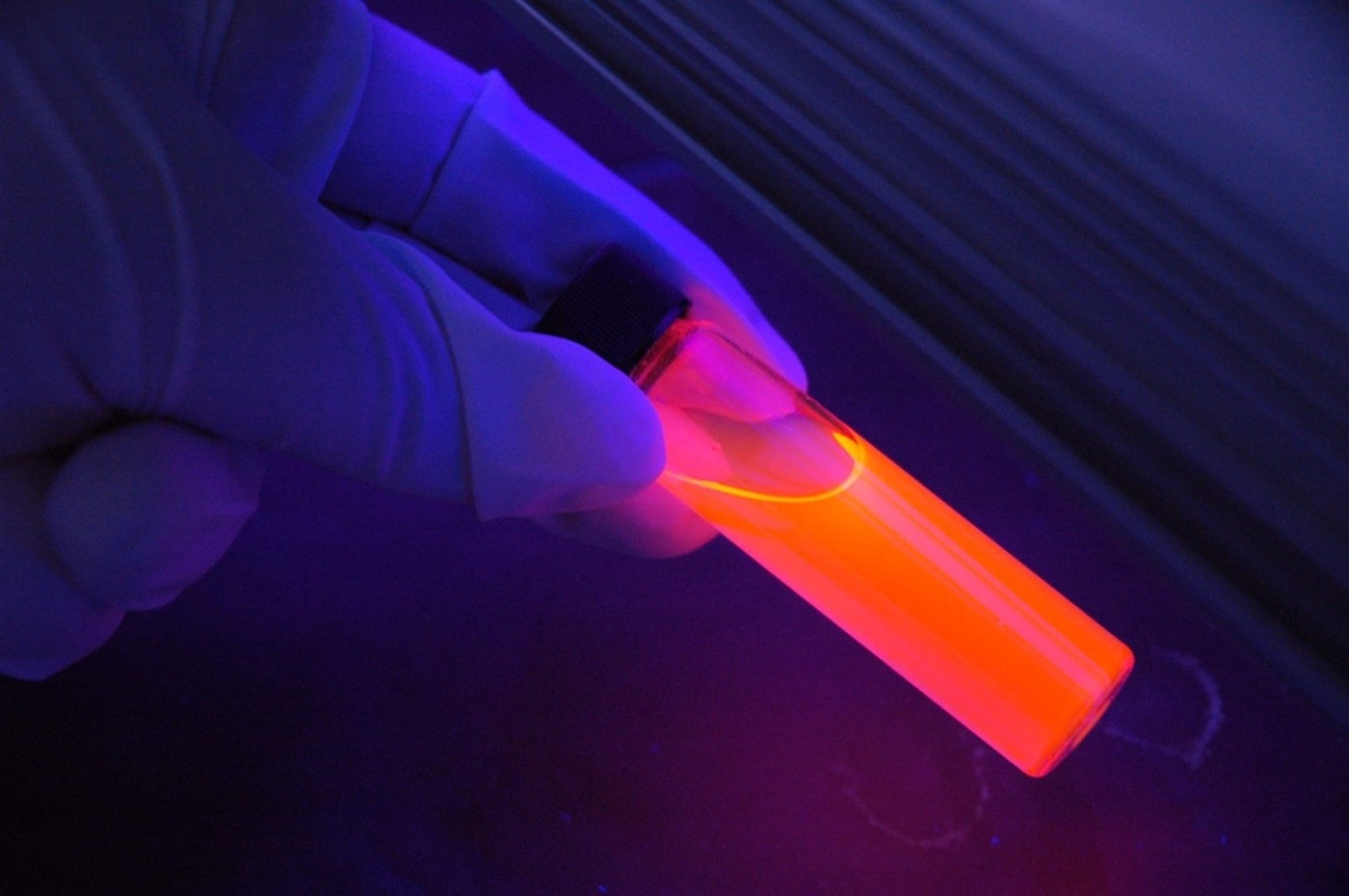

Springhares were a surprising addition to biofluorescent mammals. They are nocturnal mammals, which glow in a vivid pinkish-orange pattern concentrated on the head, legs and tail. The fluorescence comes from a set of pigments called porphyrins, which have been implicated in causing similar effects in marine invertebrates and birds. However, the purpose of the trait raises many unanswered questions. The evolutionary origins are also unclear. Scientists only recently discovered the mammals had this fascinating ability. Species which exhibit biofluorescence are often from different phylogenetic trees, with different habitats and lifestyles. It may be possible that biofluorescence might serve no purpose at all, other than – well, being really cool.

Scientists only recently discovered the mammals had this fascinating ability

Unfortunately, researchers don’t think the trait relates to another species of mammals that daub themselves in body paint before setting off to raves. The biofluorescent mammals identified thus far are mostly nocturnal or crepuscular, suggesting a correlation with night life. On the contrary, the lack of UV light during the night means in theory, less biofluorescence is possible. Some say it may have links with mating habits, but the evidence is limited. Other research suggests that prey may have evolved to hide from predators with UV vision, emitting wavelengths that are less visible. There is a huge variety in the pigments, proteins, and chemical reactions that account for the fluorescent effects, meaning that one singular evolutionary origin is less likely.

Biofluorescence and bioluminescence, although often used interchangeably, are actually two separate phenomena. Biofluorescence occurs when organisms absorb low wavelength light, and reemit the light at a higher wavelength, causing them to glow against a dark background – like the springhares. On the other hand, bioluminescence is when an organism emits light from their body due to chemical reactions that produce energy, in the form of photons.

There is a huge variety in the pigments, proteins and chemical reactions that account for the fluorescent effects, meaning that one singular evolutionary origin is less likely

Bioluminescence is widespread in the deep ocean amongst fish, squid, and gelatinous zooplankton – at depths where there is absolutely no natural sunlight. Research has suggested that up to 80% of ocean animals are bioluminescent. Some insects and mushroom also exhibit the trait, although this is seen less frequently. Symbiotic bacteria can be responsible for producing the light, as they contain photophores – which are light emitting cells. In other cases, the organism is in itself bioluminescent through oxidative dependent reactions. When a compound called luciferin reacts with oxygen, light is released. Some organisms have an enzyme called luciferase which speeds up this reaction. Depending on the location of these bacteria or luciferin-containing tissue, different parts of the animal body may light up to different extents.

Research has suggested that up to 80% of ocean animals are bioluminescent

Although still puzzling researchers, bioluminescence has been shown to confer more concrete advantages to organisms that possess the trait. In the darkness of the deep sea, bioluminescence may be used as a natural spotlight to locate prey, help organisms find food, provide defence mechanisms, or even assist in reproductive chances – unlike their rave-seeking mammalian counterparts.

Although the mechanisms and main function of bioluminescence isn’t entirely well understood, researchers are constantly finding new species and evidence for the fascinating phenomena. Collecting samples is often difficult, but a recent increase in deep sea exploration may yield new answers. The same remains with biofluorescence. Why organisms produce this “living light” still perplexes biologists, but an increasing number are hopeful that the mystery will soon be unravelled.

Comments