Last Night I Watched: ’12 Angry Men’

Recently, I rewatched the courtroom drama 12 Angry Men. Critically acclaimed and one of famed director Christopher Nolan’s favourite films, many thanks to my year 9 English teacher for exposing me to this film initially – it captivated me and my entire class. Based on the titular teleplay written in 1954, this film exemplifies the significance a tight script, creative directing, and competent acting has in inspiring an amazing movie.

Firstly, Sidney Lumet’s directing is impeccable. He knew, given the limited setting, he had to provide a dynamic presentation of the unfolding story and he does this with aplomb through a myriad of techniques. For instance, he utilises the mobile handheld cam for portions of the film, depicting the tension that fills the room. Moreover, he’s unafraid to have the camera linger on a particular character, hinting at the remaining direction of the drama. In one case, the camera lingers on Juror #3 after he shows the picture of him and his kid, revealing how that father-son relationship will prove vital eventually. Other techniques include intrusive close-up shots, deployed whenever juror #9 interjects the discussion, and zoomed out establishing shots – implemented during the brilliant scene when the other jurors grow tired of Juror #10’s prejudices. The minimal editing works too, enabling for the pressure and tension to be sustained for the majority of the 96 minutes. Ultimately, Lumet’s camerawork successfully dictates the pace and intensity of the movie; augmenting the pendulum swinging momentum of the conversation, and the volatile atmosphere.

The dialogue can be witty and charming; for example when the jury reluctantly decide to discuss things for an hour at first, Juror #10 starts to talk about a story before being sharply interrupted

The dialogue also paces the movie well. Crucial pieces of dialogue, like ones which prove the points that Juror #8 makes, are allowed time to breathe which emphasise the turning tides in the conversation. Other times, the dialogue can be witty and charming; for example when the jury reluctantly decide to discuss things for an hour at first, Juror #10 starts to talk about a story before being sharply interrupted. Of course, the source material may have been responsible for such dialogue, however the ‘50s cinematic charm is inimitable.

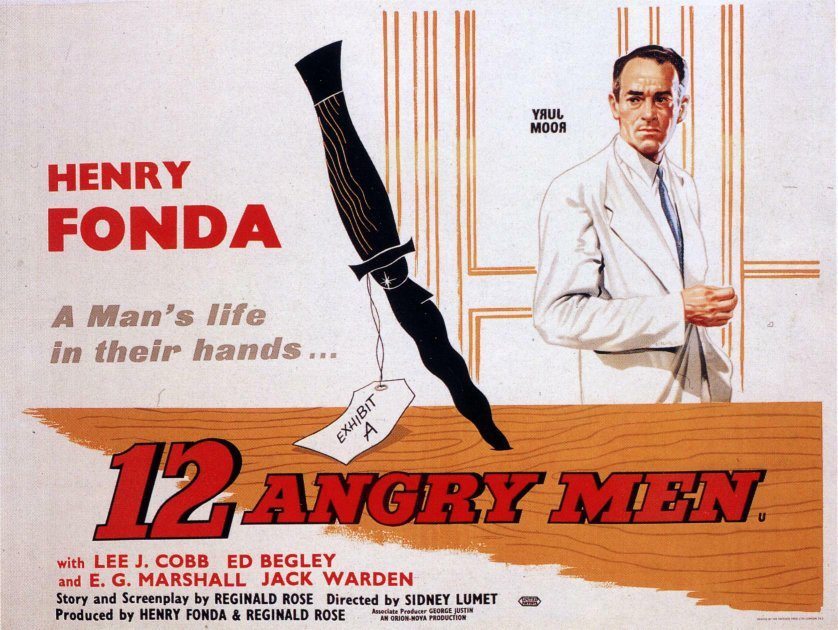

From the start, the varied characters are well established. It’s clear that Juror #7 is not emotionally invested in the case, as he’s frequently referencing the baseball game he wishes to see; just like it’s foreshadowed that Juror #3 will hold an intransigent position in the debate from his early exchange with Juror #2, and that Juror #8 would catalyse the whole discussion due to his pensive silence. The characterisation altogether is brilliant, but of course the standouts would be Jurors #8, 3, 9 and 12. Henry Fonda’s performance as Juror #8 is layered, with the character initially being reserved but grows in confidence and assertiveness throughout the runtime, in tandem with the growing legitimisation of his reservations. Lee J. Cobb as Juror #3 is expertly temperamental and intense, and Joseph Sweeney as #9 wonderfully portrays the insightfulness and mischief old people are capable of, illustrating how we shouldn’t simply underestimate them due to their suspected limited physical or cognitive abilities. Though his character isn’t the boldest, Robert Webber as Juror #12 effectively conveys a character who realises he’s out of his depth despite his early confident demeanour, shown in his stark indecision. By the end, we see him like a helpless fledgling being pulled pillar to post by Juror #8’s reasonable doubt and Juror #3’s emotive certainty.

Unsurprisingly, this courtroom drama indulges in salient themes: are people inherently good and evil?

The film’s symbolism is clever. For example, Juror #8 is wearing the brightest suit suggesting he’ll be the source of truth and justice. Moreover, the room becomes increasingly hot as the conservation becomes more intense; but, by the end, once the light is turned on, and the fan works, and the sweat from the characters dissipates, the jury reaches the just verdict as if the truth is coming to light.

Unsurprisingly, this courtroom drama indulges in salient themes: are people inherently good and evil? Is relying on a jury to exact justice fair given they may be saddled with prejudices? Can we really find out the truth of an event given it’s all about what can be proven?

12 Angry Men is simply amazing. It excels in the typical facets of filmmaking, and, regarding courtroom dramas, it doesn’t get much better than this.

Comments