How the toxic gas phosphine might indicate life on other planets

Jane Greaves, a radio astronomer from Cardiff University, was analysing the chemical composition of Venus’ atmosphere when she found something interesting in the Venusian clouds – phosphine gas. This gas (PH3) (which has an odour of rotten fish in its natural form and can damage lungs if in high enough concentrations.) it is often associated with the metabolic processes of anoxic life or human industry.

Early explorations to Venus (our other neighbour) quickly found it to be a furnace, with an average surface temperature of 471°C, clouds of sulfuric acid and a surface atmospheric pressure 92 times that on Earth

The idea of having alien neighbours in our own solar system has been especially interesting. Yet Mars often steals the limelight, This is partly due to its proximity to Earth. Early explorations to Venus (our other neighbour) quickly found it to be a furnace, with an average surface temperature of 471°C, clouds of sulfuric acid and a surface atmospheric pressure 92 times that on Earth. Not the best place to be planning a holiday. These discoveries soon dashed hopes of finding life there, and the collective search for life in our solar system turned firmly to Mars. Despite this, Venus is known as Earth’s sister planet, due to its similar size and bulk chemical composition.

This discovery was intriguing due to phosphine’s status as a biosignature.

Jane Greaves’s analysis, published in the journal Nature, was carried out using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) located on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. This discovery was intriguing due to phosphine’s status as a biosignature. These are chemicals that, when found on other planets, could be indicative of life as they have little chance of being generated abiotically (i.e. not involving biological processes) through actions like tectonics or meteorite impacts.

The concentration of phosphine in the atmosphere was also found to be 20 parts per billion, 1000 to a million times the concentration that is found here on Earth. Even with life and industry pumping more into the atmosphere, it is quickly removed due to the high concentrations of oxygen breaking it down. The instability of phosphine also means a similar process would likely happen on Venus. Researchers think the gas must be replenished by some unknown mechanism

The authors of the paper considered many alternate explanations for the source of phosphine, and emphasised they were not saying they had discovered life. “[…] we are genuinely encouraging other people to tell us what we might have missed,” Jane Graves stated, “our paper and data are open access; this is how science works.”

It can be generated abiotically but this is only possible in conditions not thought to be found on a rocky planet like Venus

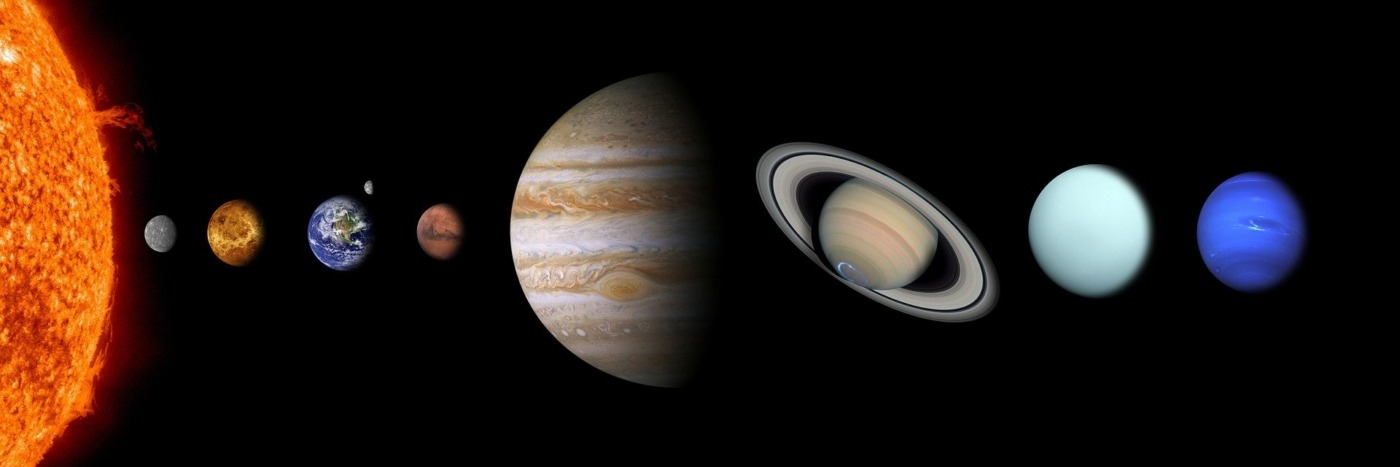

So why is phosphine gas such a good biosignature? Although it can be generated abiotically, this is only possible in conditions not thought to be found on a rocky planet like Venus, such as in the interior of gas giants like Jupiter. There are also no known chemical pathways that generate phosphine taking place in Venus’ atmosphere either. This creates an interesting scenario where if the cause of the phosphine reading is not found to be life, discoveries in the planetary chemistry of Venus are still likely to follow.

It has even been suggested that bacteria from Earth could perhaps have been brought by visiting probes into the Venusian atmosphere. However, given the vast quantities of phosphine found, it is unlikely that any visiting bacteria could multiply into the levels required to give such a strong reading. Further, the conditions there are extremely hostile to any visiting Earth organism.

It may seem unlikely that any life could survive on Venus, due to its previously mentioned hellish qualities, but at high altitudes (where the phosphine is located) the atmosphere is mild, relatively speaking. Temperature and pressure are much closer to conditions we would find on Earth and more sunlight is present than could ever reach the surface. However, the clouds are still composed of sulfuric acid and any life would likely be similar to the extremophilic organisms we find on Earth. These lifeforms are often highly specialised to extremes in pH, temperature and/or pressure, a requirement for life on Venus. Hypothetical adaptations for Venusian organisms could include an extremely thick outer cell wall to limit attack from the highly corrosive atmosphere, but this also prevents challenges for metabolic exchange with the atmosphere. Regardless, any microbe that could exist within the atmosphere would be very different to what we find back on Earth.

Overall, the discovery has shone an unexpected light on Venus and even in the (unfortunately) probable event that there is still no life on Venus, advancements in the field of planetary chemistry are likely to follow. Either way, it is an exciting discovery for our sister planet.

Comments