Scientists discover microplastics inside human organs

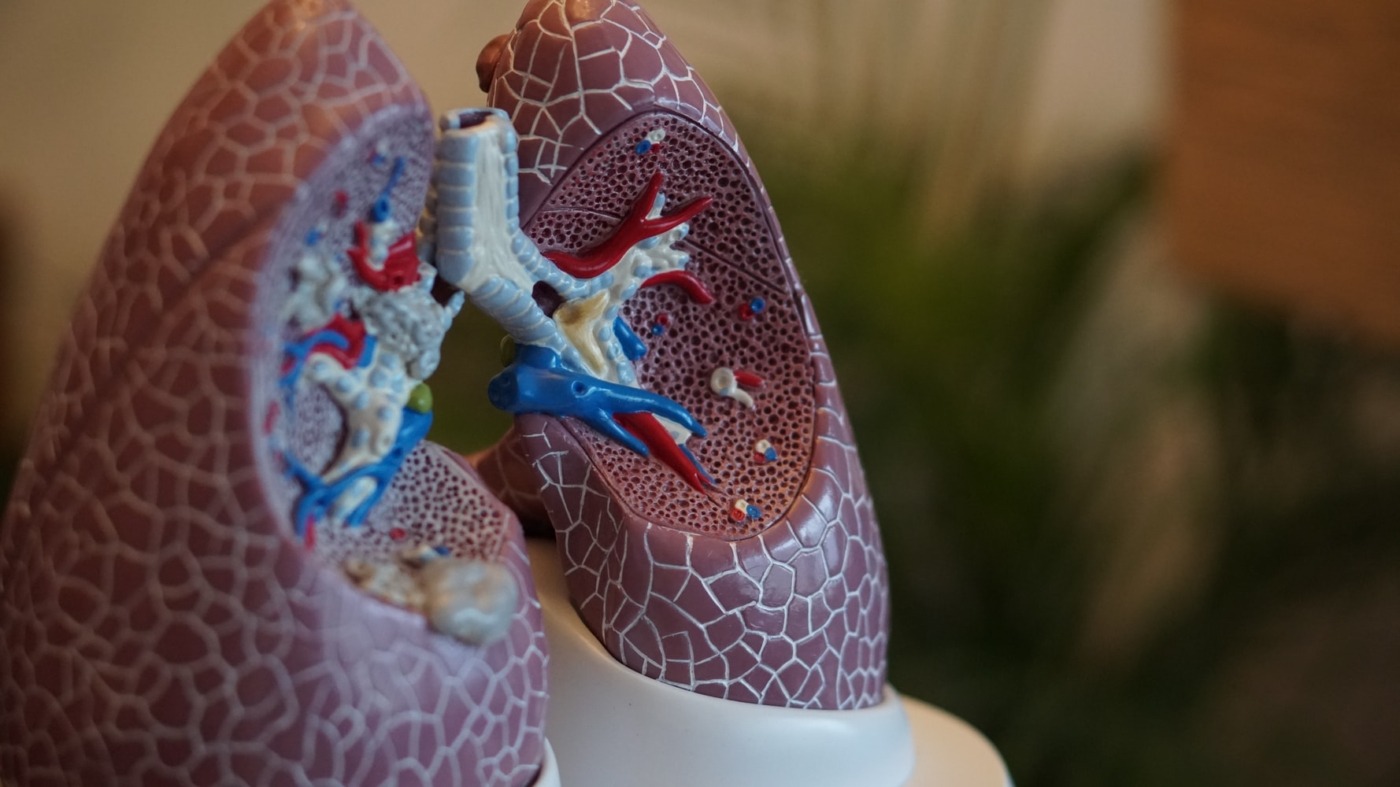

Last month, a group of scientists discovered microplastic particles in the organs of people who had recently died. A team of researchers examined the lungs, livers, kidneys and spleens of people who’d donated their bodies to medical science, and found plastic fibres in all of them. Varun Kelkar, a co-author of the study, said: “We never want to be alarmist, but it is concerning that these non-biodegradable materials that are present everywhere can enter and accumulate in human tissues, and we don’t know the possible side effects. Once we get a better idea of what’s in the tissues, we can conduct epidemiological studies to assess human health outcomes. That way, we can start to understand the potential health risks, if any.”

The experts believe that microplastics likely enter our system after we consume food and drinks that contained them. They have also been found in the air that we breathe. A microplastic is less than 5mm, and nanoplastics are thinner than a hair. As co-author Dr Rolf Haden said: “If we allow micro and nanoplastics everywhere in our environment – in dust, in air, in drinking water, in food – then a natural consequence is that we get exposed. It would be naïve to believe there is plastic everywhere but just not in us.”

Last month, a group of scientists discovered microplastic particles in the organs of people who had recently died

If scientists are worried about consuming so much plastic, then surely the best approach is to tackle it before it enters the environment. But where do we start? First, it is important to recognise the scale of the problem. A study led by the UK’s National Oceanography Centre found that there could be as much as 21 million tonnes of microplastic in the Atlantic Ocean, and studies found it in bottom-living sea creatures and sediments taken from the North Sea. Once ingested by small creatures, microplastics work their way through the food chain – it was found that one in every 50 mammals washed up on UK shores had ingested microplastics. They’re already part of the human food chain, and a WHO analysis found more than 90% of the world’s most popular bottled water brands contained plastic. This plastic is going nowhere fast – it is estimated that it will take centuries to decompose.

There are some things we can do to limit microplastics entering the environment. Avoiding plastic containers and beauty products containing microbeads will reduce the number of plastics in landfills, and air drying your clothes cuts back on the fibres released by washing. Similarly, buying clothes with non-synthetic fibres can reduce the number of microplastics that end up down the drain. And, if you’re worried about consuming animals with plastic in their system, limiting your intake of meat and fish can reduce your exposure.

A WHO analysis found more than 90% of the world’s most popular bottled water brands contained plastic

Individual actions, however, are only a small part of the picture. If we want less plastic pollution, it is imperative that we use less plastic. Currently, plastic production is increasing exponentially, with a projected 33 billion tonnes produced each year by 2050. Society can do its part by significantly curtailing unnecessary single-use plastic items, but the government needs to get involved. Some steps have been taken – the UK banned microbeads in cosmetics in January 2019, while the EU has proposed new measures to curb their use – but more needs to be done.

In the long term, action should be taken to improve rubbish collection and recycling systems, thus preventing plastic waste from leaking into the environment, and to improve recycling rates. In Europe, only 30% of plastic is recycled, and that drops to 9% in the USA. Scientists are also working on new ways to break plastic down into its most basic units, which can be rebuilt into new plastics or other materials.

In Europe, only 30% of plastic is recycled, and that drops to 9% in the USA

Plastic is absolutely everywhere, and humanity is faced with a two-pronged question. How do we look to the future to reduce the level of plastic in our environment? And, just as important, how do we cope with the sheer volume of plastic that is already there? As Janice Brahney, a scientist at Utah State University, says: “What should be imprinted on the broader public views is although we’re only noticing this problem now, it is not a new problem. It’s going to get worse before it gets better. There’s so much that we don’t know, it’s really difficult to fully comprehend the implications of plastics that are absolutely everywhere.”

Comments

Comments are closed here.