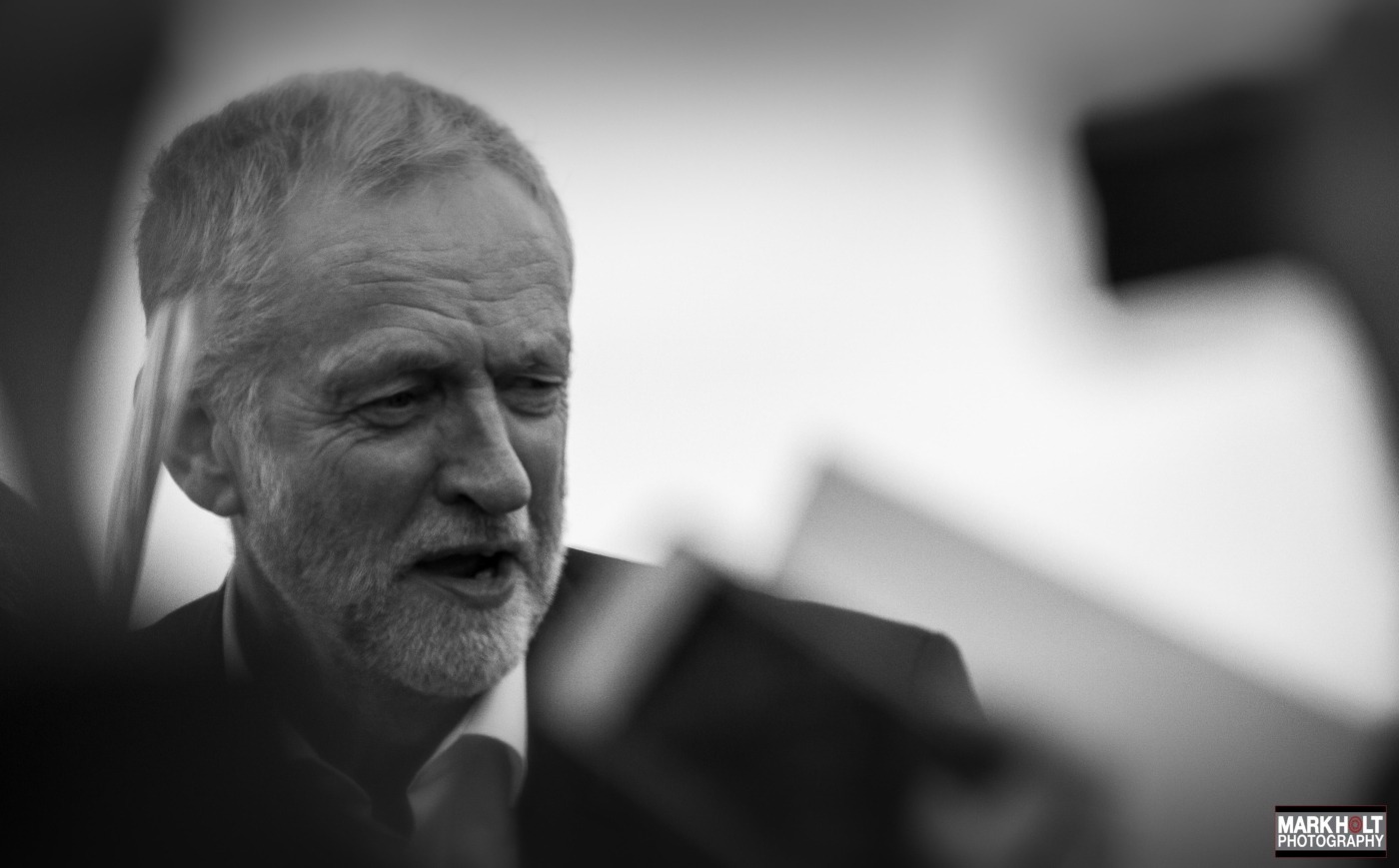

Reflecting on five years of Jeremy Corbyn

After a brutal defeat in the 2019 general election, the unlikely Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn is finally wrapping up his tenure at the top – so, what better time to reflect on the highs and lows of his nearly five years in power?

Corbyn was not expected to win the 2015 Labour leadership election – indeed, he was only nominated by many Labour MPs to ensure that the Left of the party was represented. He benefitted hugely from two main factors. Firstly, his rival candidates all represented New Labour and, as they had lost two consecutive elections, it was felt that it was time to move on. Secondly, the rules were changed by Ed Miliband, allowing new members more voting powers than ever before, and a huge influx of voters backed Corbyn. He won more than 60% of the vote, and membership rose considerably under Corbyn, making it one of the largest political parties in the continent.

He won 60% of the vote, and membership rose considerably under Corbyn.

The new leader set about doing things differently. He invited members of the public to send him questions to ask in Prime Minister’s Questions, sought to get the Labour membership more involved in decision-making and asked for a “kinder, gentler politics” that ended personal abuse. He appointed a number of allies, including John McDonnell (Shadow Chancellor) and Diane Abbott (International Development; then Health and, finally, Home Secretary), to his Shadow Cabinet, and it was the first Shadow Cabinet with more women than men.

But the knives were also out for Corbyn. Criticisms were frequently raised about Corbyn’s supposed support for the IRA and other terrorist groups – this, after a storm when he refused to sing the national anthem, contributed to an idea that Corbyn was ashamed of the country he sought to lead. A lifelong anti-nuclear campaigner and pacifist, he faced questions about whether he would pull out of NATO, scrap the UK’s nuclear deterrent (or, if not, be prepared to use it). There were talks of an army mutiny, with one general stating that “you can’t put a maverick in charge of a country’s security”. And then, there were the inevitable personal attacks, with many critics calling him “scruffy”.

Criticisms were frequently raised about Corbyn’s supposed support for the IRA and other terrorist groups.

The first sign of the issue that would sink Corbyn came in February 2016, when PM David Cameron announced a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU would be held in June. A Eurosceptic all his life, Corbyn tried to sit on the fence as his MPs and many of his young voters advocated for Remain. Older Labour voters tended to support Leave and were furious at Corbyn backing Remain – meanwhile, EU supporters were furious that Corbyn was lukewarm in his support of the EU. Reconciling this position would prove hugely difficult for Corbyn throughout the rest of his tenure.

An extra issue for the public was Corbyn’s ideology – he had openly professed an admiration for Karl Marx, and his Chancellor was a man who said he wanted to overthrow capitalism. After the referendum, Labour MPs decided that it was time for him to go, and orchestrated mass Shadow Cabinet resignations – more than two dozen ministers quit, and Corbyn lost a no-confidence vote by 172-40, but he simply refused to leave. The MPs had another plot, organising a new leadership election, but they failed to rally behind a figure. Ultimately, Owen Smith went up against Corbyn and the leader was re-elected, strengthening his position at the top.

Corbyn lost a no-confidence vote by 172-40, but he simply refused to leave.

No-one had high hopes for Corbyn when new PM Theresa May announced a snap election in 2017. Corbyn was underwater by 20% in some polls, and the Labour leader’s reluctant Remain position in the EU referendum was expected to be widely-exploited by Theresa May, who’d called the election with the pretext of strengthening her hand in negotiations. It was to be an easy win for the Conservatives, increasing their majority and destroying Corbyn once and for all.

That, of course, is not how things panned out. Whatever his criticisms, Corbyn was a highly-effective campaigner, mobilising the young vote and casting himself as a cultural phenomenon. He was backed by grime artists (#Grime4Corbyn trended during the election) and he received an enthusiastic reception at Glastonbury, where crowds of thousands chanted ‘Oh, Jeremy Corbyn’. Corbyn’s ascendancy came as the May campaign essentially collapsed, with a tax on social care and the choice to avoid debates among her weaknesses. Although the Tories remained the largest party, they in fact lost seats and were forced into a de facto coalition with the DUP. Meanwhile, Corbyn gained 30 and won 40% of the vote – he openly suggested that May should step aside and allow him to form a minority government.

Whatever his criticisms, Corbyn was a highly-effective campaigner, mobilising the young and casting himself as a cultural phenomenon.

Unsurprisingly, this was a Parliament dominated by Brexit, and Corbyn’s Brexit position was continually under fire. He was mocked for trying to sit on the fence, attempting to appeal to both Brexiteers and Remainers, and Labour was criticised for not really having a coherent policy. As the Conservatives went for Brexit and the Lib Dems angled themselves as an unequivocal Remain party, few could explain where Labour sat on the biggest issue of the day. Eventually, Labour came out in favour of a second referendum after pressure from the unions and the threat of emergent party Change UK, but he was later groaned at by a Question Time audience for pledging to stay “neutral”. Corbyn’s refusal to say whether he’d back his own renegotiated Brexit deal went down very poorly with voters.

Corbyn also became embroiled in a major anti-Semitism row which, along with Brexit, dominated his final few years in office. Back in 2016, Corbyn announced an inquiry into anti-Semitism and other forms of racism – its findings of an “occasionally toxic atmosphere” soon proved at odds with a raft of stories. A number of MPs quit the party, either victims of anti-Semitic abuse or in solidarity of those who were, and Corbyn repeatedly came under fire for being far too slow to act, and too lenient when he did. In a much-publicised incident, Corbyn ally Ken Livingstone was suspended for anti-Semitic remarks in 2016 – despite claims of zero tolerance, the issue was finally resolved when Livingstone quit the party himself two years later. Jewish newspapers and the Chief Rabbi urged people not to vote for Corbyn and, in May 2019, the Equality and Human Right Commission launched a formal investigation into the party. The only other party to be investigated in this way was the BNP.

Corbyn also became embroiled in a major anti-Semitism row which, along with Brexit, dominated his final few years in office.

In 2019, new PM Boris Johnson called a December election – unlike 2017, Corbyn was viewed as an actual contender for the job. Johnson made 2019 a Brexit election, and his cry of “Get Brexit Done” resonated with a weary public in a way that Corbyn’s elaborations didn’t. The party voted twice against holding an election at all, a fact that the Conservatives made a lot of noise about, and there was open scepticism that Labour’s manifesto was affordable and deliverable. In an interview with Andrew Neil, Corbyn refused to apologise for his handling of anti-Semitism.

Corbyn was framed as economically useless, happy to condone racism and ambivalent on the biggest issue of the day, and it chimed – Labour’s vote share collapsed, winning 32.1% of the vote and losing 60 seats. The party now had only 202, its worst result since 1935, and the Tories broke into Labour’s red wall, winning seats that had never voted Conservative before. On the doorstep, Corbyn’s leadership was frequently cited as a major reason that people did not vote Labour. One of their MPs, Neil Coyle, summed up the situation: “There were people who said they knew Boris Johnson was a liar and a cheat but they still preferred him over our leader.” It wasn’t the only reason that people voted Conservative, but it was a big one.

Corbyn was framed as economically useless, happy to condone racism and ambivalent on the biggest issue of the day.

The writing was on the wall now – Corbyn had to go. He called for a period of reflection and kicked off a new leadership election. At the time of writing, it seems likely that Sir Keir Starmer, Corbyn’s Brexit Secretary, is likely to win. The so-called ‘continuity Corbyn candidate’, Rebecca Long-Bailey, has essentially collapsed in the running – she was much derided for giving Corbyn’s leadership “10 out of 10” after the historic defeat.

What will Jeremy Corbyn’s legacy be? For his supporters, the country missed out on a genuinely empathetic and kind leader who hoped to bring about the societal change they feel is desperately needed. For his detractors, it’s good riddance to a terrorist sympathiser and incompetent who was dangerously close to power. Corbyn himself has said that the government’s investment in society during the coronavirus outbreak is a vindication of his economic proposals, and that society will fundamentally change at the pandemic’s end.

For his supporters, the country missed out on a genuinely empathetic and kind leader who hoped to bring societal change.

Corbyn was certainly heavily-maligned (with the fairness of some criticisms open to your opinion), but he represented a big difference in the status quo and managed to mobilise a force of young voters who felt previously ignored by political discourse. His political career is marked by two losses (one highly substantial) and a lot of controversy, but his supporters never lost sight of him as a force for good and change – even if he wasn’t the most successful politician, his cultural impact cannot be understated. It’s likely that Starmer (if he wins) will attempt to steer away from Corbynism and back to the middle-ground, seeing this period as an unsuccessful experiment, but Corbyn’s time as tenure will not be so easily erased.

Comments