Cutting edge exoskeleton technology allows paralysed man to walk

Ground-breaking research has allowed a paralysed man to move all four limbs using an exoskeleton that reads his mind. A two-year study, published in The Lancet Neurology, by French researchers based at the Clinatec biomedical research centre at the University of Grenoble trialled the system, which works by recording and interpreting brain signals.

Thibault, the 30-year-old who participated in the trial, has been paralysed for four years following a 50m fall from a nightclub roof but was able to successfully walk 10 metres and perform a series of complex arm movement with the aid of the AI-driven exoskeleton. He described taking his first steps as being like the “first man on the Moon”.

He described taking his first steps as being like the “first man on the Moon”

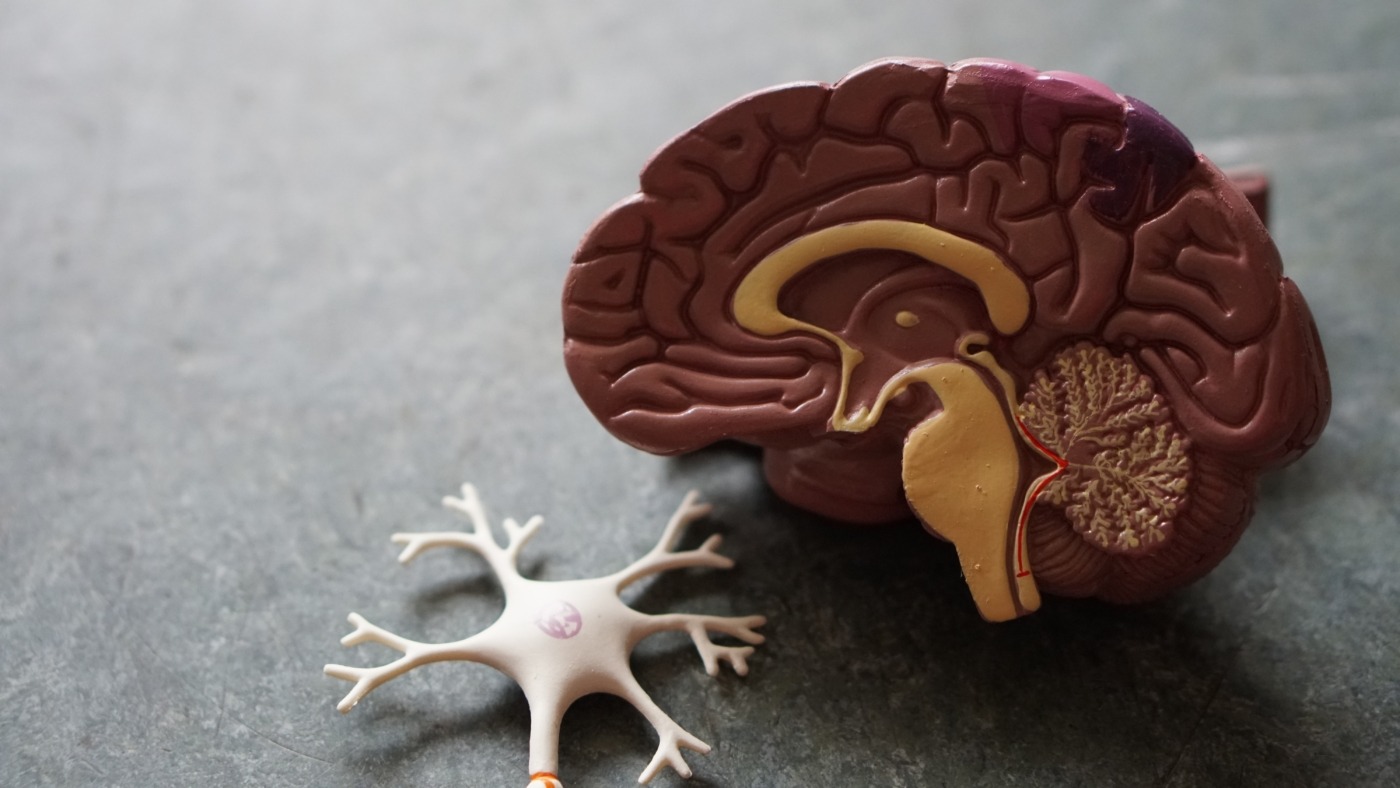

Prior to being strapped into the exoskeleton, Thibault underwent surgery to place two implants on the surface of his brain. The implants were recording devices, each containing a 64-electrode grid, and were placed either side of Thibault’s head to span the sensorimotor cortex, the part of the brain that controls movement. These implants wirelessly communicate with a computer, making them safer than past trials which have utilised wired brain-machine interfaces.

Over the period of the two-year study, the machine’s algorithm trained itself to recognise and understand Thibault’s brain waves as he moved an avatar around a video game on a screen. When the AI was deemed reliable enough, it was time for Thibault to try the exoskeleton suit. Once strapped in, merely thinking about walking would propel the robotic suit to move his legs forward.

Once strapped in, merely thinking about walking would propel the robotic suit to move his legs forward

It is thought that this ground-breaking discovery, which builds on previous research, will boost the quality of life and autonomy for the 20% of people with traumatic spinal cord injuries who end up quadriplegic.

Whilst the study is a notable advance on existing approaches to enable paralysed people to walk again, the exoskeleton is not yet ready to move out of the laboratory. In its current form, a ceiling harness must be attached to Thibault to reduce the risk of him falling in the exoskeleton. Laboratory aside, the high cost of such technologies also means it’s far from being implemented into a clinical environment. Professor Alim-Louis Benabid, President of the Clinatec executive board made clear that: “This is far from autonomous walking”.

Laboratory aside, the high cost of such technologies also means it’s far from being implemented into a clinical environment

The French scientists are continuing to refine the exoskeleton technology; of the 64 electrodes on each implant, only 32 are currently being used. Additionally, the potential to use more powerful computers and AI to decode the brain signals and gather information is a promising next step to bringing this technology closer to the real-world. Other future plans include the development of finger control to allow patients like Thibault to pick up objects.

Going forward, three more patients have joined the trial with the next step being to eliminate the need for the ceiling suspension system so that the exoskeleton could begin to be imagined outside the laboratory; and consequently, in the future, help better the quality of life of patients by extending their mobility.

Comments