“It certainly leaves you thinking”: review of Birmingham Rep’s ‘Blue Orange’

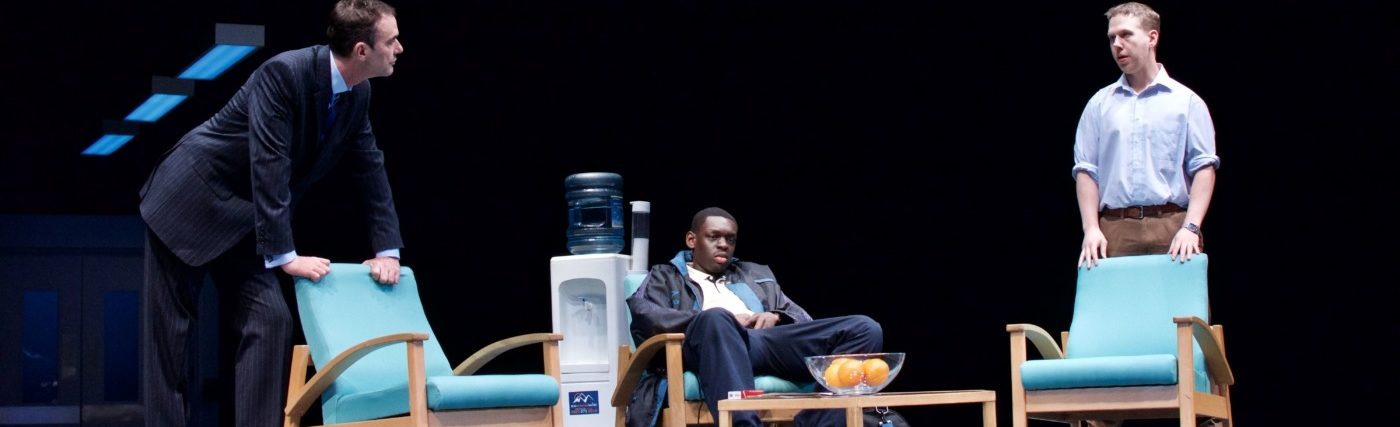

Blue Orange, the award-winning play by English playwright and screenwriter Joe Penhall, has been given a fresh face by the Birmingham Rep nearly two decades after it first debuted. Young talent Ivan Oyik, a British-Ugandan student of the Guildford School of Acting, makes his stage debut as Christopher, a black Londoner who has been sectioned under the Mental Health Act. With the end of his period of detention looming, his case is the subject of a heated dispute between two psychiatrists involved in his care at the psychiatric ward: consultant psychiatrist Robert (Richard Lintern), and Bruce, his trainee (Thomas Coombes) — both of whom are white.

To summarise their positions briefly, Bruce believes Chris that is a danger to himself and to others, and needs to remain in the hospital, while Robert argues for his release on the grounds that he would be better off in the community, for his own wellbeing, and more critically, because of a lack of beds. With neither willing to compromise, a lengthy but enthralling debate ensues between them.

Young talent Ivan Oyik, a British-Ugandan student of the Guildford School of Acting, makes his stage debut

For those without a background in race and mental health in Britain, black people are disproportionately sectioned. In fact, this occurs at four times the rate of white people. They are also more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, a phenomenon that critics have been linking to racism for decades. Chris’ blackness isn’t a coincidence; it’s central to the play’s social commentary.

Although Blue Orange premiered in 2000, it remains as timely as ever, if not more so. With Brexit looming as well as reforms to the Mental Health Act, which aim to reduce the number of patients involuntarily detained, what better time to devote nearly two and a half hours to questions about the enforcement of involuntary psychiatric detention? And what better time to ask these questions in relation to racism and xenophobia?

Admittedly, the play’s focus upon race isn’t quite as intense as I thought it would be. This isn’t a straightforward condemnation of the institutional racism within psychiatry: it’s much more than that. Blue Orange makes an astute political commentary, not only on the complexity of the relationship between blackness and psychiatry, but on psychiatry more broadly, and how ‘clinical decisions’ about matters such as NHS funding can be as much about the overinflated egos of psychiatrists as they are about the wellbeing of individual patients.

What better time to ask these questions in relation to racism and xenophobia?

In particular, it draws attention to an incredibly important, but difficult-to-discuss sociopolitical phenomenon: the appropriation of radical critiques of psychiatry by self-serving psychiatrists. Service user collectives such as ‘Recovery in the Bin’ have drawn attention to this — how critiques originally made to empower patients are increasingly used by psychiatrists as a means to justify the withholding of essential care within the context of an overstretched NHS. It’s a difficult can of worms to open, but Blue Orange tackles these issues in a nuanced and intelligent manner.

Chris, true to reality, is often asked to leave the room while the two psychiatrists meet. As a result, the majority of the dialogue is comprised of the debate between the warring doctors. It could be argued that Chris should have more of an opportunity to voice his experiences as a black, working-class man who appears to be suffering from severe mental illness. It feels like Chris serves as comic relief, his amusing quips preventing an otherwise incredibly dark play from being a totally depressing experience. Clearly, this is worthy of critique: why is it that black characters so often get the role of providing comic relief to predominantly white audiences? Are we laughing with him, or at him?

It’s a difficult can of worms to open, but Blue Orange tackles these issues in a nuanced and intelligent manner

At the same time, the choice to tell Chris’ story through the dispute between two white psychiatrists seems to reflect an awareness of the fact that patients like Chris have very little voice; rather, they’re shuttlecocked between services, between ‘clinical opinions’, between identities. While he says relatively little, Chris is an incredibly sympathetic character, played brilliantly by Oyik, whose performance is expressive and charismatic.

The play ultimately ends underwhelmingly. With little having been resolved, I think many in the audience feel unsatisfied. But perhaps that’s the point.

It’s sometimes said that art is there to ‘comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable’. True, the humour infused throughout Blue Orange ensures that it’s nowhere near as disturbing as it has the potential to be. But it certainly leaves you thinking. A neat, positive ending could result in people leaving the theatre feeling complacent, the opposite of what Blue Orange aims to achieve. If it helps shrug some out of complacency, or makes an anti-psychiatry appropriating psych reflect on their hypocrisy, it’s done its job.

Blue Orange is at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre until Saturday 16 February. You can buy tickets here.

Comments