The Foundations of Finance – Wages

As Warwick students, it wouldn’t surprise you if financial terminology such as ‘income’ and ‘salary’ were among the words uttered most frequently on campus. Along with getting a girlfriend, and a parking space in term 3, the quest for a high-paying graduate scheme resides in the upper echelons of a Warwick student’s ambitions. But why do wages matter? What can we learn from the role that wages play in our economy?

Quite simply, wages are the reward for one’s labour. This is a monetary compensation paid by an employer to the labourer, usually per hour, as a reward for sacrificing their time and effort to conduct a task.

Ancient Greece and Egypt operated with waged labour. The Athenian currency- the ‘Talent’ (around 26kg of silver), would trade for 9 years of work for a skilled labourer. But it was under capitalism where wages became paramount to a decent standard of living. In a free-market, wages are determined by the supply and demand for the labour. Factors that determine the demand for labour include the demand for the good that this labourer is producing (derived demand), as well as the productivity of the labour. The supply of labour depends largely upon the barriers to entry to the market. These barriers usually are as a result of a lack of skill. Very few people have the ability to nut headers in from 18 yards out, hence the supply of world-class centre back’s is very small and Harry Maguire’s wages are therefore completely justified.

Despite our endless obsession with them, the numbers we see on our graduate contracts are an arbitrary figure

Further factors determining the supply of labour include the population, as well as non-monetary characteristics such as working conditions. Those who work on oil rigs, in a dangerous, isolated environment are paid what are known as ‘compensating wages’. These are wages that will be slightly higher because of the unattractive nature of their work.

Despite our endless obsession with them, the numbers we see on our graduate contracts are an arbitrary figure. These are nominal wages, they do not take into account the cost of living and inflation can render the positive effects of rising wages redundant.

For example, Venezuela recently increased their minimum wage by 155%. Although this appears to be a moment to call for champagne, the prospects of a better lifestyle are quickly dashed, given that inflation is projected to reach 1,000,000 % (yes, that is 1 million percent) by the end of 2018 in Venezuela. These wages adjusted for inflation are known as real wages.

Real wages are amongst one of the key yardsticks for economic progress. They demonstrate whether productivity, the output per worker, is on the rise. Higher productivity is key to unlocking a higher standard of living. However, since the financial crisis, the UK has been suffering from slow productivity growth.

Figure 1: Productivity has barely risen in recent years (Source: ONS)

This ‘productivity puzzle’ partly explains why over the last 30 years the real wages of the working and middle classes have stagnated.

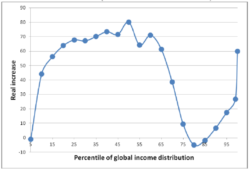

Figure 2: Increases in Real Income 1988-2018- Milanovic (Source: World Bank)

Former World Bank economist Branko Milanovic’s ‘Elephant Chart’ is incredibly significant. Incomes have risen significantly over the past 30 years for the world’s poorest, as well as the top 1%. The 75th-90th percentile, which consists of the working and middle class of the developed world, have seen wages stagnate. This lack of improvement in the standard of living is no doubt responsible for the rise of political alternatives to the neoliberal consensus, such as the far right league in Italy and Trump.

With 77% of students working during their time as undergraduates, increases in the minimum and living wage will help those who are in employment. These wage increases can result in inflation, with firms having to increase prices as a result of higher labour costs.

According to The Economist, Warwick students are the 8th highest earning graduates in the UK, 5 years after graduating (£33,865)

Those who are relying on savings may lose out if the inflation that results from higher wages exceeds the interest rate. This is because the increase in the level of prices is higher than the interest accrued from holding money in a savings account.

For all the talk of the squeezed middle Warwick students fare very well. According to The Economist, Warwick students are the 8th highest earning graduates in the UK, 5 years after graduating (£33,865). Whether flourishing wages will continue to be the case remains, due to the graduate market population increasing year on year. Whilst making ends meet important, it may be worth considering what else we value apart from the number of 0’s at the end of our pay cheque.

Comments