Learn from Literature: culture, identity and Britain

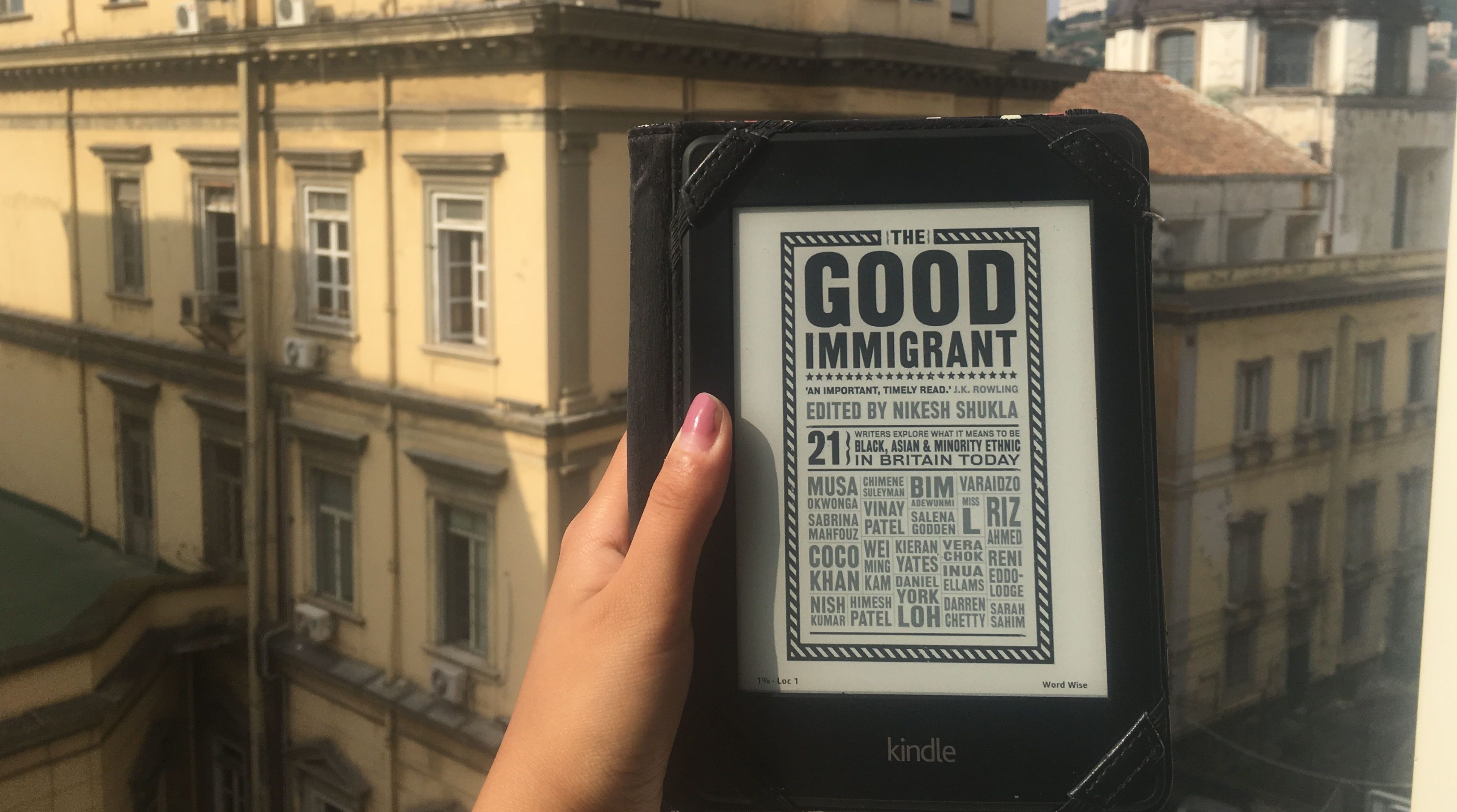

Recently I read The Good Immigrant edited by Nikesh Shukla. This timely and much needed book is a collection of 21 essays by first, second and third generation immigrant writers of various nationalities and ethnicities to the UK about their relationship with culture, identity and Britain. Aiming to counter stereotypes, it contains personal stories and reflections that ponder big questions.

Most of the authors are writers, journalists, comedians, actors and artists by profession; many are major names like Nish Kumar, Riz Ahmed, Reni Eddo-Lodge. In this sense, the book helps to fill another gap of representation and is important for those like me who do not dream of following the typical path of becoming a doctor, lawyer or banker. It has made me view identity through new eyes and I believe ought to be read by everyone to understand the conflicts faced by so many Brits today. What I learnt from reading this book is a very personal lesson for me, that will remain with me and provide me with confidence for a long time to come.

I found myself having continuous “Oh my God” and “Yes! Finally! So true!” moments

I found myself having continuous “Oh my God” and “Yes! Finally! So true!” moments. My Kindle highlights from this book are endless. Some essays spoke to me more than others, but every single essay captured me at some point, perfectly articulated a thought I have struggled with, or offered me some kind of truth. Reading it was both comforting and galvanising; I wished I too could stand up and shout from the rooftops.

Its relatability was simply new and refreshing to me. I discovered the sheer range of immigrant experience, as well as the uncanny similarities in the difficulties faced when stuck between two cultures. For instance, whereas the experience of an Indian family living in rural Cambridgeshire seemed a far cry from my own upbringing as an Indian in London, the ways of thinking of a Chinese or Turkish Brit were almost identical to my own. The rumination of a mixed race writer on cultural mixing, and whether it is possible to label one as either ‘black’ or ‘white’, totally captured my feelings about cultural hybridity and the interconnectedness of my ‘Indianness’ and ‘Britishness’.

There is not always resolution, and not always hope either

For each writer there was a kind of coming of age, a shattering of innocent idealisms, a realisation that they have been fooled by the benevolence of the world. It is an important wake up call for all Brits. These turning points involved different encounters for all: racism ranging from the casual to the blatant, ignorant comments, cultural appropriation, uncomfortable reminders of the sufferings of ancestors. Some essays are positive and others are not. There is not always a resolution, and not always hope either. Many are raw, painful and depressing to read. It captures the present state of non-white Britain, full in the knowledge that on the one hand, numerous immigrant communities are thriving in the UK – finally beginning to make money and climbing the ranks in sectors such as finance, law, technology to name a few. For many of these people, heritage is not an impediment and can be easily thrown off.

On the other hand though, for women, for those in the arts, the struggle continues and they are constantly reminded of their ethnicity, particularly since the Brexit vote. The writers are generally fairly young, but the racial rebukes of 70s and 80s classrooms that are distinct memories of my parents are also not ignored. Writers jarringly use humour to recount uncomfortable situations in airports and audition rooms, reminding us of just how normal they can be.

They must constantly recall what the UK has done for them and repay this hospitality with submissiveness

The paradoxes are called out and made abundantly clear; immigrants are welcome, but only good immigrants that conform to conditions. Immigrants ought to be grateful, indebted, respectful and obedient. They must constantly recall what the UK has done for them and repay this hospitality with submissiveness and by not standing out or asserting themselves. These rebellious voices now finally come to the fore in The Good Immigrant as the writers speak out about hurt, confusion, ignorance and everything in between. There are paradoxes and inconsistencies within the book too. Where some writers question and define terms and labels like the arbitrariness of ‘East Asian’, others employ terms that might exclude others. There is no consensus or set understanding of what it means to be an immigrant, but the conversation is opened for debate.

The Good Immigrant will now always be an important book to me. It can become part of the slowly growing list of art and media that is helping me to find my own voice as a writer, teaching me that I too may have something valuable to say. From being ashamed of my culture as a child, to falling back in love with it and realising how many others feel the same way and can come together. It made me more determined to contribute to this growing trend, and maybe help others to better understand their identity, as this book did for me.

Comments