Science Explains: the hard science of soft metals

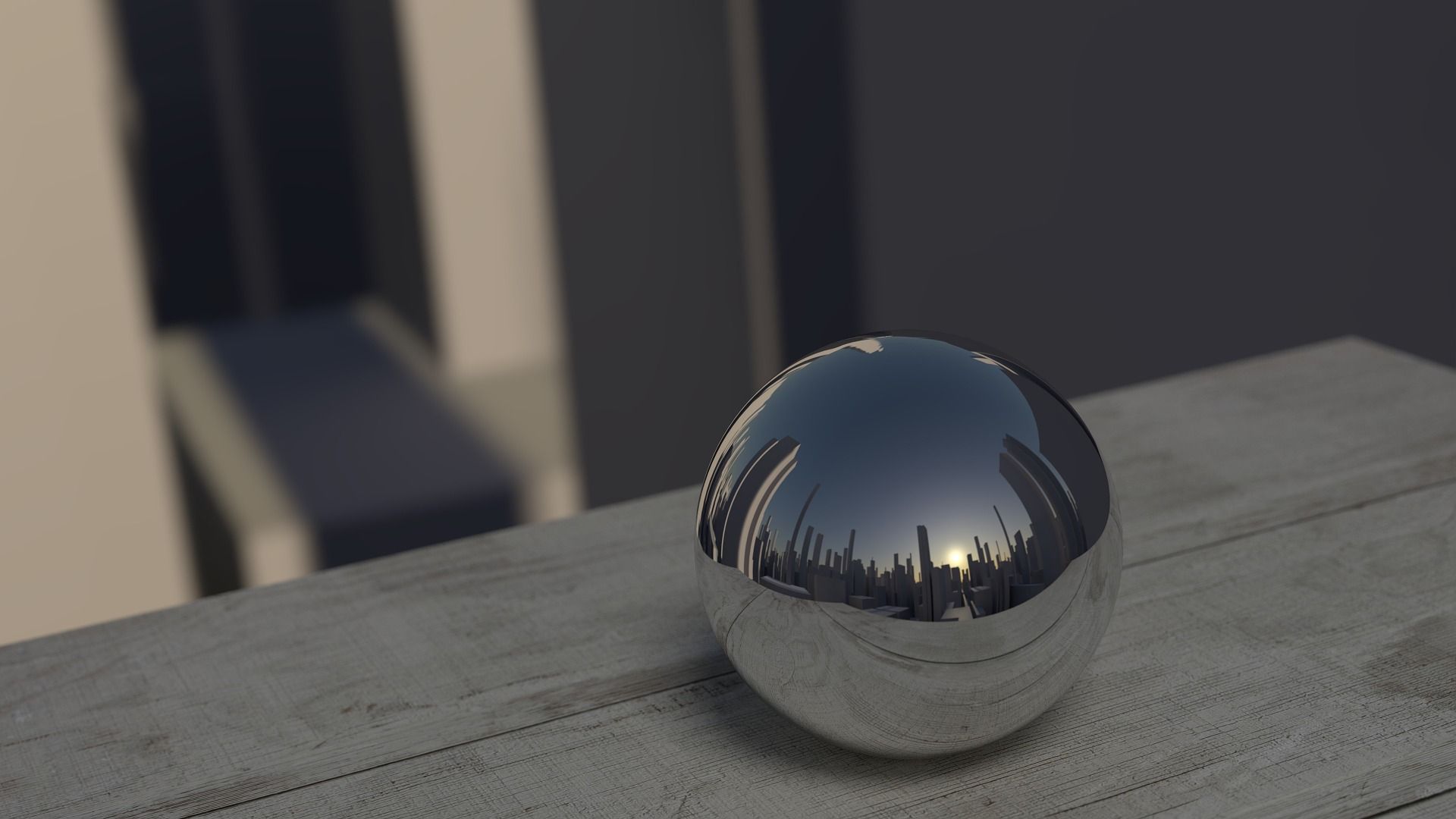

If you’re on social media at all, you’ve probably seen one of the latest challenges going around – people share images of a fairly smooth metallic ball, which they have fashioned from a crumpled piece of tinfoil, and thus provoke people around the world to try and replicate the feat. Purportedly, this effect is achieved using only simple, everyday tools such as the hammer and sandpaper. Is such a thing possible and, if so, how is it done? Well, it transpires that there’s some fairly old science behind the tinfoil spheres.

The effect was first demonstrated by a YouTube user called SKYtomo in March of this year. He began with a crumpled ball of tinfoil and hammered in until it was highly compressed and much smaller. He then sanded it under running water with several different grades of sandpaper, producing a smooth but somewhat mottled and dull sphere. After that, all that was required was a further bit of sanding and polishing to make the sphere shiny and reflective. There have been sarcastic tweets suggesting that the same effect can be achieved by putting sheets of tinfoil into the microwave, alas a landfill full of broken microwaves is proof that this is not the case. Now, metal normally requires intense heating before it can be moulded into a new shape. However, aluminium is unusually soft, which means it is malleable enough to be reshaped by force alone, although it takes a fair bit of time and patience.

There have been sarcastic tweets suggesting that the same effect can be achieved by putting sheets of tinfoil into the microwave, alas a landfill full of broken microwaves is proof that this is not the case

The tinfoil rolls we use begin life as giant aluminium ingots, which are then rolled into flat metal sheets (these are typically a fraction of a millimetre thick and miles long). They are then heat-tempered in order to become more flexible, before being cut up and packaged. If you wanted to make a ball, you’d want the softest and most pliant form of this foil that you could find – this would be the purest sheet and one that had been subjected to the highest degree of the heat treatment.

This tinfoil play may seem a bit frivolous, but it has an interesting real-world analogue. When Japanese swordsmiths produce certain types of katana, the steel is riddled with impurities and the carbon is distributed irregularly throughout the metal. In order to work with the imperfect steel, they practice something called ‘kitae’ (roughly, forging) – the metal is repeatedly hammered and folded back upon itself, working out the impurities and helping to distribute the carbon content more clearly, according to Edward Hunter, an armour conservator with the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If you wanted to make a ball, you’d want the softest and most pliant form of this foil that you could find

A similar effect could be achieved at home, although there are some key differences. The general techniques are essentially the same (except the high-temperature treatments you’d need to temper steel), but the blade would dull much quicker – aluminium isn’t as hard as steel and it wouldn’t hold its sharpness for particularly long. You’re also more likely to find open pores on the inside, rendering a foil blade weaker than a steel one.

Although it doesn’t initially appear that way, fashioning a tinfoil ball has a very interesting real-world precedent – there’s no practical purpose to their creation unless you count the opportunity of forging a connection to ancient metalworking methods.

Comments