‘Studio Ghibli’ and the art of storytelling

Earlier last month, Academy Award and Oscar nominated animator, Isao Takahata, died at the age of eighty-two. You’d be forgiven for not knowing who he was, as it is his works of art (materialised in Anime form) that has continued to capture the souls and hearts of viewers more so than his name. Takahata was the co-founder of ‘Studio Ghibli’, well-known for its animated films: Ponyo, Howl’s Moving Castle, Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro among others. This year marks the 30th anniversary of Totoro and another of the studio’s seminal works called Grave of the Fireflies, a war-time animation following the lives of brother and sister as they attempt to survive the wasteland that is WWII Japan’s countryside. The devastating effects of war, not only on this irresistibly cute pair, but on the nation as a whole has embedded Fireflies into everyone’s minds as a film for the ages. In more ways than one, it is testament to the fact that animation isn’t a genre of film just for children because it has the ability to depict harrowingly life-like situations and lessons in more poignant ways, sometimes far better than live action films can. Yet, it is an attraction to all age groups that has made ‘Studio Ghibli’ films so famous and loved in both the Eastern and Western world.

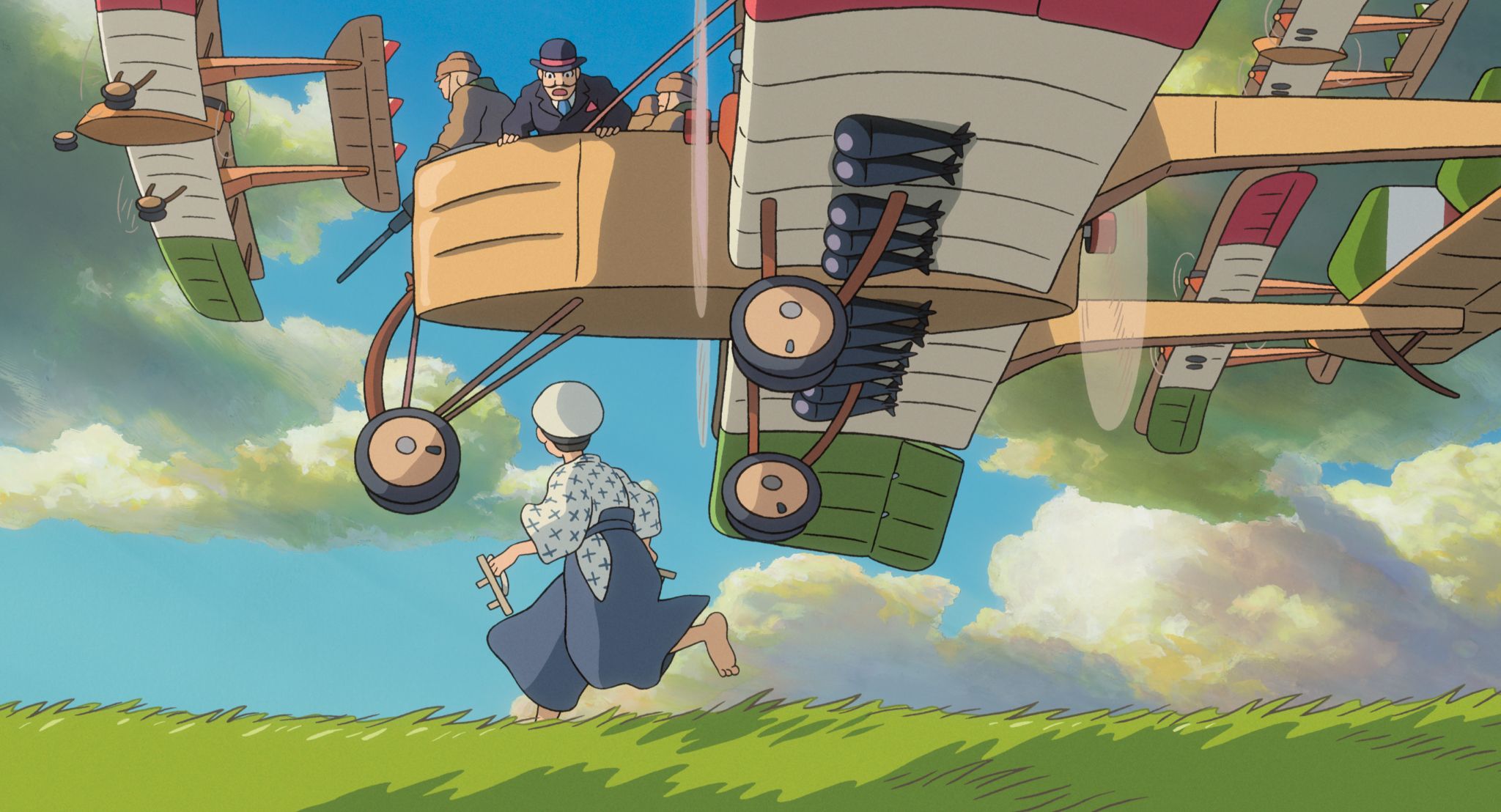

A combination of masterful drawing, animating and musical composition make for stunningly visual and emotionally-engaging films

Part of Studio Ghibli’s success has to do with the breath-taking craftsmanship that goes into making each one. Combine this with unusual, yet gripping storylines, the ‘Studio Ghibli’ films were creating Anime films that people across the world were undoubtedly enjoying immensely. However, beyond this, there are other reasons for its success amongst Western viewers. Unsurprisingly, there is already a market for Japanese animated story-telling in the form of Anime series. Even if you’ve only had the fortune of watching a dubbed version of Pokemon or Dragonball Z, you’ve been touched by the far-reaching influence of the genre. Since there is already interest, the move from Anime serials to ‘Studio Ghibli’ films isn’t a massive jump.

Yet, I was mesmerised. When I saw it on TV again I dragged my best friend over to watch it, who loved it equally as much as I did

The films also have a compelling mystical realism attached to them. Almost every storyline, exempting Fireflies, is absurd but magical, creating confusion yet interest and joy simultaneously. For example, take The Cat Returns: ‘Haru’, a little girl, saves a cat from being run over by a car, only to find out he is a talking cat-prince who wants to marry her. Haru is then transformed into a cat and taken to the prince’s world where they embark on many adventures. Spirited Away, most famously known for its black, Grim-Reaper-like character that wears a white Japanese mask, involves another little girl called ‘Haku’. Haku finds herself trapped in a spirit world as her parents have morphed into pigs on account of their gluttonous appetites. Most ‘Studio Ghibli’ films share this mysticism and sense of adventure. One of my favourite memories as a child was discovering Howl’s Moving Castle, which is often aired on daytime English television. I remember being extremely confused at the characters in the film and why they were all non-human or grotesque-looking, save from the young female protagonist. Yet, I was mesmerised. When I saw it on TV again I dragged my best friend over to watch it, who loved it equally as much as I did.

Another common theme running through them all is the youth of the protagonists, often a young girl. This offers films like My Neighbor Totoro a youthful sense of hope throughout. This goes hand-in-hand with the magical realism aspects of the film, as the viewer is left wondering whether the strange black bugs or the night bus in the shape of a cat are real, or parts of the children’s imaginations. Regardless, the audience of ‘Studio Ghibli’ films are invited to leave behind any notions of reality or logic and lose themselves in the magic of the unknown. No matter if they are Japanese-speaking or not, anyone would be able to see the everlasting appeal in these films.

Comments (2)

It’s a thoughtful article but there are some errors and other references left out. Haku is the boy in Spirited Away; Chihiro/Sen is the girl. In reference to the Studio Ghibli movies that dwell more on reality than the magical besides Fireflies, there’s also Only Yesterday, Ocean Waves; and to a lesser extent The Wind Rises and When Marnie Was There (although both films include some somewhat fanciful scenes).