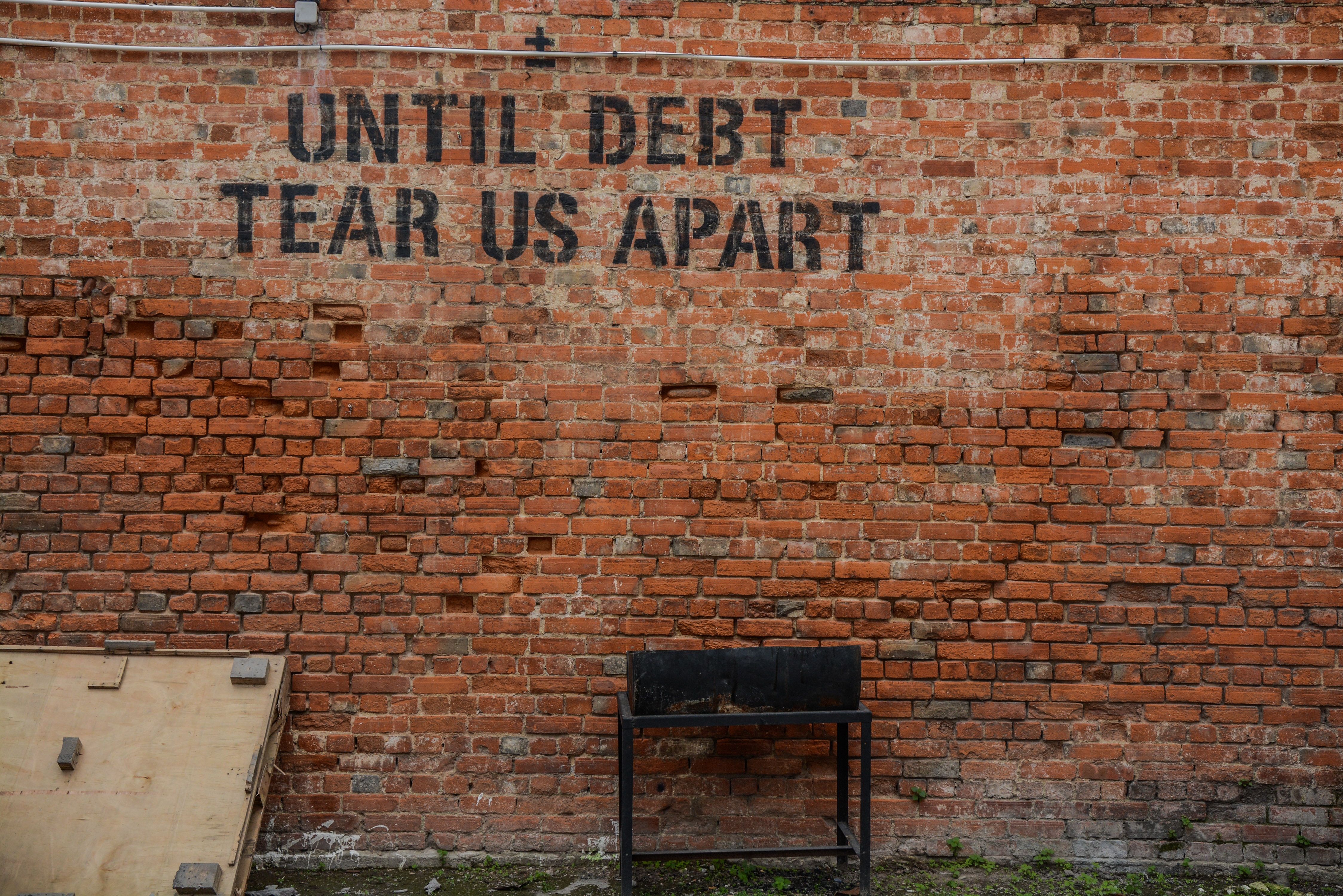

Student debt, distress and discontent: why the threshold rise is a sham

The government’s most recent announcement on student debt sounds great. Thousands of graduates will have their student loan repayments suspended until they earn £25,000 or more. Around 600,000 students will apparently make potential savings of up to £24,000. In a bid to thwart criticism of tuition fees that have more than trebled, the government have sought to find a quick and easy solution to pretend that they do care about Britain’s young.

The truth is that the (temporary) freezing of tuition fees at £9250 and a rise in the repayment threshold to £25,000 are at best superficial measures. The government refuses to get to the root of the issue, and overhaul the consumerist perception of students, or even make certain degrees better value for money. This can be seen everywhere. The fact that universities such as Warwick significantly lowered grade boundaries for courses in clearing last year shows that capitalism is trumping education, and that the money students are bringing in is more significant than their education. This has only happened because of high tuition fees, which has rendered students little more than pound signs.

Half-hearted policies prove that the government is not prepared to invest time and money into Britain’s future

Policies and perceptions such as these must be challenged by students and graduates. An entire overhaul of the university system is required to put students’ education and needs first, yet our government only makes slow attempts at reform in an attempt to show that they care about our young people. They do not want to give us a viable solution to the ‘buyer’s market’ or the debt we are in.

Instead, half-hearted policies prove that the government is not prepared to invest time and money into Britain’s future. Shambolic ideas such as ‘commuter’ degrees and the charging of fees according to contact hours have been thrown around by ministers without considering what these policies would mean for disadvantaged students. Such policies would only reinforce inequality, both at university and in society, in a system that already favours young people from wealthier backgrounds.

The government seems to expect poorer students to make these sacrifices for the convenience of their wealthier peers

Having varied tuition fees according to contact hours would stop bright young people from disadvantaged backgrounds pursuing STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) degrees, which would increase inequality in those professions. Similarly, “commuter” degrees penalise the poor by forcing students from disadvantaged backgrounds to stay at home to avoid debt, denying them the full university experience and discouraging them from attending top universities, unless they are lucky enough to live down the road. The government seems to expect poorer students to make these sacrifices for the convenience of their wealthier peers. As students, we must oppose this.

If the government truly cared about the fact that the average student graduates with around £50,000 of debt, their first rational step would be to reduce the amount of interest we pay on our loans. The current rate of interest is incredibly high at 6.1%, which students start accumulating as soon as they take out the loan. This exposes the rise in the repayment threshold as little more than giving with one hand, whilst taking with the other. It is a futile attempt at giving the illusion the government is investing in our futures. Debts are increasing and rates are unlikely to be changed anytime soon.

Yes, more students are accessing higher education than ever before, but disadvantaged pupils are still deterred from applying to top universities

Rhetoric is all well and good, but we are being sold selected truths. Yes, more students are accessing higher education than ever before, but disadvantaged pupils are still deterred from applying to top universities, have seen their maintenance grants scrapped, and are charged obscene levels of interest on top of their ever-growing loans. Only when students become more than consumers in the eyes of ministers and their institutions will we have a meaningful solution on the horizon, rather than the reluctant shuffles towards reform that we are presently given.

Comments