The fetishizing of genius

The genius has rattled our television sets and movie theatres with its seemingly infinite arsenal of snarky retorts and one-liners. They’ve permeated through our culture clad in witty charm and fearless intent, becoming the archetypal cinematic hero of our time. Whilst somewhat lacking in more conventional heroic qualities, there’s no denying that they’re inherently watchable, now more than ever. Over the past few decades, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that dialogue in film is undergoing a trend of snappy exchanges, which perfectly plays into the hands of the intellectually superior genius. Film audiences have witnessed this style of writing countless times in the form of characters like Sherlock Holmes, Tony Stark, and Mark Zuckerberg. Their words effuse from their mouths effortlessly as they over-conceptualise some smart, yet perfunctory, thing. That being said, they remain one of the most quotable and mimicked characters in modern film culture.

The genius has rattled our television sets and movie theatres with its seemingly infinite arsenal of snarky retorts and one-liners.

There is a strange sort of reverence that goes beyond mere admiration of the genius’s intellect; my fear being that it has manifested in the form of a fetish – a fetish of venerating impossibly smart people, as we see them outthink their way out of any scenario. It has become this unhealthy envy, not entirely dissimilar to the ‘wealth porn’ that some of us find ourselves indulging in; more pertinent examples of this include films and TV shows like Entourage or even The Wolf of Wall Street to a certain extent (though this can be construed as more of a critique on the excessive lifestyle). Thus, cinema has birthed the genius porn, whereby we sit in awe of really clever people talking really quickly about really smart things. It’s also worth noting the homogeneity of these geniuses; almost all of them are straight, white males – an unhealthily singular depiction of such extraordinary characters.

Leonardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street. Image credit: Paramount Pictures

It is perfectly understandable why audiences enjoy watching geniuses with this gnawing curiosity; primarily, it’s the escapism factor that fuels this. We live vicariously through these characters in order to escape our comparatively ordinary lives. We watch Benedict Cumberbatch’s devilish charms and embrace the fantasy of actually being Sherlock Holmes. We see almost everything one could desire in Tony Stark – an enormously wealthy genius superhero who also happens to be the most charismatic person in any room. Society puts these characters on a pedestal and labels them as the pinnacle of human evolution. Of course, audiences have always empathised with characters irregardless of their intellect.

There is a strange sort of reverence that goes beyond mere admiration of the genius’s intellect; my fear being that it has manifested in the form of a fetish

From the early days of theatre and novelistic writing to more modern forms of storytelling like films and comic books, audiences latch on to well-drawn out characters and the struggles they face. But there is a more honest and intimate connection with characters that are defined by the choices they make, and not the clever words they say. The fundamental laws of character growth dictate that the hero must evolve and change as a consequence of their actions, and how they respond to unforeseen events. But these geniuses that we see onscreen are simply destined for greatness; they were born with abilities that far surpass those of ordinary human beings, meaning they automatically deserve our attention and empathy. It’s an unhealthy message as much as it is lazy writing.

The genius trait is, however, more forgiving when it forms the bedrock of a character’s arc, or if it falls in line with biographical material. For instance, the film Still Alice features Julianne Moore as an esteemed linguistics professor who is diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease. Her intellect is the most central part of her character, and so in losing this integral trait the audience sees her change in the way she leads her life, becoming a more realised character in the process. Yet, the genius trait is so often gratuitously used by writers, so that it just becomes another additional character trait in an effort to make the character more watchable. And when it comes to the needlessly attributed genius trait, there is no greater sinner than the character of Will Hunting.

Julianne Moore in Still Alice. Image credit: Sony Pictures Classics

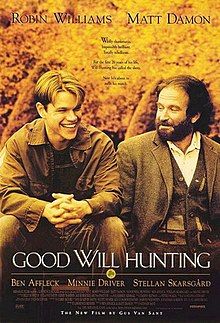

Anyone who is vaguely familiar with the zeitgeist of 90s film culture will most likely be aware of the much-beloved Good Will Hunting. The critics lauded the film for its stellar performances and potent writing from debutants Ben Affleck and Matt Damon. In truth, it’s a decently made film with a particularly outstanding performance from Robin Williams. However, it dramatically fails in the presentation of Will Hunting’s character, to the extent that the underlying morals of the film are at severe odds with current issues of social mobility and the omnipresent fallacies surrounding the ‘deserving poor’. Now, if my take on Good Will Hunting has already ruffled your feathers, you may wish to stop reading at this point – it only gets worse from here.

When it comes to the needlessly attributed genius trait, there is no greater sinner than the character of Will Hunting.

Firstly, yes, I am fully aware that the film won the Academy Award for best original screenplay and is almost universally acclaimed. As an aside, I would just like to remind people that the Academy is not this objective entity imbued with a divine right to select the very best film of the year. In reality, the Academy is a political body that favours the wealthiest and most renowned production companies. Back to the matter at hand, the question I pose is this: why does Will Hunting have to be a genius? Why is it not enough for Will to be a downtrodden, young, directionless Bostonian who suffers severely from his traumatic past? Why is Will more deserving of our attention and empathy than his other blue-collar peers? It’s quite apparent how the film answers the latter questions: it’s because Will is wicked smart.

Image credit: Miramax Films

Of course, it’s not enough for Will to just be a victim of domestic abuse. That’s far too dull for a Hollywood story. No, he has to be born with near-supernatural abilities to make him one of the ‘deserving poor’. He has to blessed with an intellect that instantly makes everything revolve around him. This is perfectly epitomised in the form of Stellan Skarsgård’s character, who only takes an interest in Hunting after discovering his untapped potential. I find absolutely no cinematic or behavioural benefit in Will being a genius, other than the fact that the spoils of Youtube have allowed viewers to relive Hunting’s deftly crafted retorts in short five-minute soundbites, which, evidently, has become an issue in film culture in and of itself.

Ultimately, the writers of Good Will Hunting have implicitly stated that we need to root for Will Hunting, because he has a great mind that is destined to be cultivated and nurtured, unlike the rest of the common, painstakingly average folk. In essence, you can be poor, you can be hurt, you can be scarred, but unless you were born with special gifts, you’re not worth anybody’s time and attention.

They were born with abilities that far surpass those of ordinary human beings, meaning they automatically deserve our attention and empathy. It’s an unhealthy message as much as it is lazy writing

Further yet, the current political climate is an accurate reflection of this toxic mentality. It’s this pervasive idea that immigration is perfectly fine, but let’s only allow the good ones in. Sure, you just travelled a thousand miles over treacherous waters and perilous lands to escape a war-torn country, but are you really worth our resources if you’re an uneducated and unskilled worker? Ok, you may have grown up in an environment with sub-standard schooling and minimal funding in the public sector, meaning you become stuck in a paralysing cycle of systemic poverty, but are you worth reforming if you sell drugs on the street to make a living? Whilst the questionable writing of Good Will Hunting, and issues of the deserving poor may appear to be two completely unrelated matters on the surface, in actuality, the likeness is uncanny.

Fetishizing genius and prodigious talent can be dangerous. And, quite frankly, it’s not worth anybody’s time and attention.

Comments