A copy of a copy: The literary journey of Denis Villeneuve from Arrival to Blade Runner 2049

There is no such thing as an original idea. Science fiction often grapples with the notion of dwindling originality; copies of copies being a common theme in sci-fi. Fresh fiction is hard to find, which is why Arrival, the 2016 Denis Villeneuve directed sci-fi movie, caused such a stir on release.

Ostensibly, Arrival was an original, fascinating prospect. Diverging from “standard” alien invasion tropes, Arrival was heralded as a unique take on the genre. It was cerebral, thematic, artistic and, apparently, original.

Yet, as the film crossed into its third act, it became clear that Arrival wasn’t as unique as it had promised. The fascinating discourse of language and communication (a clever thematic choice, which posed questions that hadn’t been addressed before in invasion films) dropped away, leaving a story that was… oddly familiar.

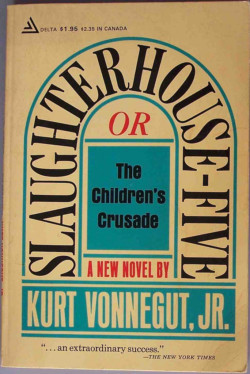

The literary inspiration for Arrival? Image credit: Christo Drummkopf, Flickr

The last act of Arrival is a startlingly similar shadow of Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse 5. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) mirrors Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut’s hero, who is unstuck from time and thus traverses it in out-of-order moments, aided by the Tralfamadorians, the aliens whose philosophy overarch Slaughterhouse 5. Villeneuve probably had the Tralfamadorians in mind when he created his aliens.

Yet, as the film crossed into its third act, it became clear that Arrival wasn’t as unique as it had promised.

The film turns its back on the themes it had explored throughout in order to begin a discussion on time, by transposing the discussion which Vonnegut started.

That’s not to say that Villeneuve “copied” Vonnegut’s work, nor is there a problem if he did. Fiction, is inspired by other fiction (though there is an argument about whether Arrival constitutes as a nod, a homage or even an adaptation). However, Villeneuve’s reference to Slaughterhouse 5 poses an issue in its execution. To continue Vonnegut’s discussion on time and space, Villeneuve abandoned themes that had carried significant weight throughout his movie.

Instead of forming a discussion with Vonnegut’s themes or using them to highlight his own, Villeneuve created a copy of them, showing little directorial mastery. He told us a story, but didn’t tell us why the story was important, or why it was relevant to the story he was telling us before. On the surface, Arrival was a good replication of Vonnegut’s story, but the themes underneath were left disconnected and undiscussed.

Villeneuve’s latest movie, however, is a more convincing replicant. Blade Runner 2049 (the sequel to Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi masterpiece) is a rare opportunity to see a filmmaker learning from his previous work, even in the experienced stages of his career. 2049 is a progression from Villeneuve’s handling of literary source material in Arrival. While it’s true that Villeneuve is working with different writers this time, it’s discernible that he has grown in his ability to interact with literary source material.

Ryan Gosling in Blade Runner 2049. Image credit: Sony Pictures Releasing

Blade Runner 2049 oozes with literary allusions. Upon meeting Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), Officer K (Ryan Gosling) identifies a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. The joke is a wry one: Deckard (one Freudian slip of the tongue away from Descartes), is Ben Gunn, the madman exiled on Treasure Island, just as Deckard is cast out and disconnected from his society. Deckard smirks at K’s identification and grumbles, “He reads”.

The same can be said of Villeneuve. Literary allusions are deeply embedded into this film. Gosling’s character mirrors Kafka’s Joseph K, meandering the modern city, ostracised and hunted, helpless as mechanisms whir around him. Nabokov’s Pale Fire is referenced, the presence of a physical book within the movie waking the audience to the fact that this film is not, in fact, a Treasure Island; an isolated promise of wealth within an empty sea. Rather, 2049’s treasure comes from its discourse with other texts. In order to get all that one can from this movie, 2049 urges the viewer to interact with the literature surrounding it and thus shows us that Blade Runner is as relevant today as it ever was.

Villeneuve’s latest movie, however, is a more convincing replicant. Blade Runner 2049 … is a rare opportunity to see a filmmaker learning from his previous work

Villeneuve crafts this depth by learning from his mistakes in Arrival. Rather than simply overlaying his movie with literary allusion, he engages with it and continues the discussion of previous material.

While talks of a third Blade Runner poses questions about the absence of originality in Hollywood, Blade Runner 2049 has demonstrated the ability of a director to develop, even late in his career, and the way in which films need to interact with the material that surround them.

Read The Boar’s review of Arrival here

Comments